Press freedom and the common man

COMMENT | It’s so easy to take press freedom for granted, isn't it? Did you get worked up upon reading reports that the Philippines had arrested Rappler CEO Maria Ressa?

I doubt it. I know that those of us in the media fraternity were upset, but why should a member of the public care? Most likely, it seems like a distant issue.

By now, so does the murder of Saudi dissident journalist Jamal Khashoggi last October, although at the time many were angered by the brazen operation allegedly ordered by Saudi crown prince Mohammed bin Salman (as an aside, the more cynical among us could argue that it makes it easier to forgive and forget if the alleged perpetrator comes bearing bags of cash).

But why does press freedom deserve a prominent place in the layman’s estimation? Particularly at a time when everybody feels qualified to be a citizen journalist or social commentator/influencer?

As far as I am concerned, it's still a critical barometer of the quality of life society can offer to its citizens.

That’s why we have to speak up when an injustice is carried out against the free press (and indeed, that other bastion of independence from the executive, the judiciary).

The detention of Ressa (photo) was almost certainly at the prodding of the not-so-hidden hand of would-be authoritarian leader Rodrigo Duterte.

So great is the desire of many political leaders to control the narrative that lives are often snuffed out should they get in the way. I am not saying it's ever gotten that bad in Malaysia, it hasn’t. But the tight grip of power has been felt before.

One of my first glimpses of this was when I was 14 and I saw lord president Salleh Abbas in conflict with then-prime minister Dr Mahathir Mohamad.

Essentially, Salleh and other leading judges were dismissed for having the temerity to make judgments of their own accord on the legal status of a fractured Umno.

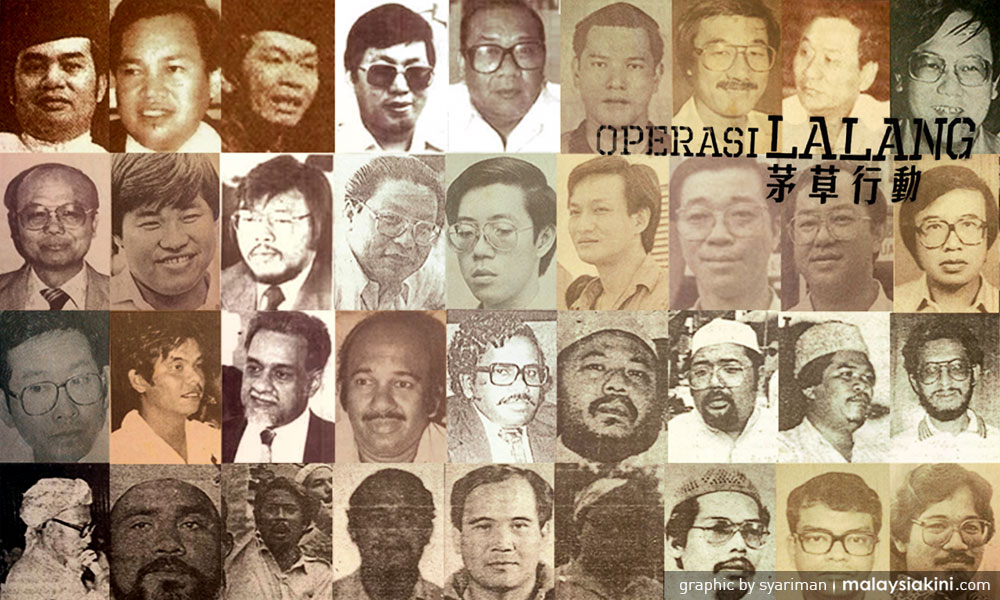

This occurred around the same time as a clampdown on the press that included The Star being shut down for five months just for reporting the detentions under Operation Lalang.

At that age, it occurred to me that something was wrong, but I could not possibly see the ramifications.

You see, back then, the general advice was to keep your head down in the event of any trouble. "Jaga rice bowl," they called it.

Nothing has really changed, for there is a whole barrage of people trying to tell you that bread and butter issues are what really count. But you know what? We’ve lived through an era of economic prosperity that was coupled with restricted civil liberties. It doesn’t work.

Slippery slope

Ultimately, a lack of appreciation for the importance of principles like the separation of powers, and the independence of the judiciary and media is what leads down the slippery slope to dictatorship.

I guess former prime minister Najib Abdul Razak can only look back at the control that his one-time mentor Mahathir had over the narrative, and lament how he was undermined by the freedom of his people to speak their thoughts.

There will be plenty of obfuscation, mind you. In fact, that appears to be Najib's new tactic, as he plays to a gallery with both a short memory and unbelievably poor critical assessment.

Discrediting the purveyor of contrary news is another alternative to silencing it. Duterte, in his attacks on Rappler, targeted its ownership, saying that it was the pawn of foreign elements interfering in his country.

He also implied that those opposed to him were corrupt journalists, and therefore ‘legitimate targets for assassination.' Some of his tactics mirror those of US president Donald Trump, who merely attempts to silence dissent by crying foul – or more accurately, "fake."

Labelling dissenting opinions as fake news is such an obvious ploy, and yet it has caught on with authoritarian leaders of all shapes and sizes. And their blind followers.

Just four months ago in Brussels, I attended a vigil honouring three dead journalists. Slovak writer Ján Kuciak, Bulgarian TV host Victoria Marinova and Daphne Caruana Galizia (photo), a reporter from Malta.

All three were investigative reporters exposing financial crimes, and Kuciak and Galizia were slain in targeted assassinations, while Marinova was raped and murdered at a time she was working on a number of big stories. And this, mind you, is in supposedly free and independent Europe.

According to the New York-based Committee to Protect Journalists, at least 53 journalists were killed in 2018. No less than 34, included Khashoggi, died as direct retaliation for the work they were doing. I find it heartbreaking.

The free press in Malaysia has a long history of being compromised and infringed. From the 1961 takeover of Utusan Melayu by Umno to regular raids on Malaysiakini offices, there has often been intimidation of journalists by politicians who wish to be their master.

Should we be grateful that things aren’t so bad in Malaysia that people aren’t getting killed for the stories they write? Or push on to higher standards of investigative and analytical journalism?

Certainly, we have to acknowledge a paradigm shift in the last year, with a new government promising greater freedom. While it does feel like more democratic spaces have opened up in the media, it must be noted that restrictive legislation has not been done away with.

Furthermore, a new government used to friendly relations with the free media may not be so thrilled as more and more questions are asked of it.

We are at a crossroads. The recent closure of institutions like the print edition of the Malay Mail (after 122 years) and Tamil Nesan (after a mere 94) show that the media is under threat, not just from politicians, but also by the wild frontier of digital consumption. Who really knows where we will be in a decade?

I would venture to say that the Malaysian in the street needs to recognise his or her role in the changing landscape.

Media ownership is critical and the more you support independent media, the less beholden it is to those with vested interests. The more you back those who are willing to be the voice of the people, the more you help safeguard your own future.

MARTIN VENGADESAN is a member of the Malaysiakini team.

RM12.50 / month

- Unlimited access to award-winning journalism

- Comment and share your opinions on all our articles

- Gift interesting stories to your friends

- Tax deductable

Martin Vengadesan

Martin Vengadesan