BOOK REVIEW | Rise of an accidental politician as empires fell

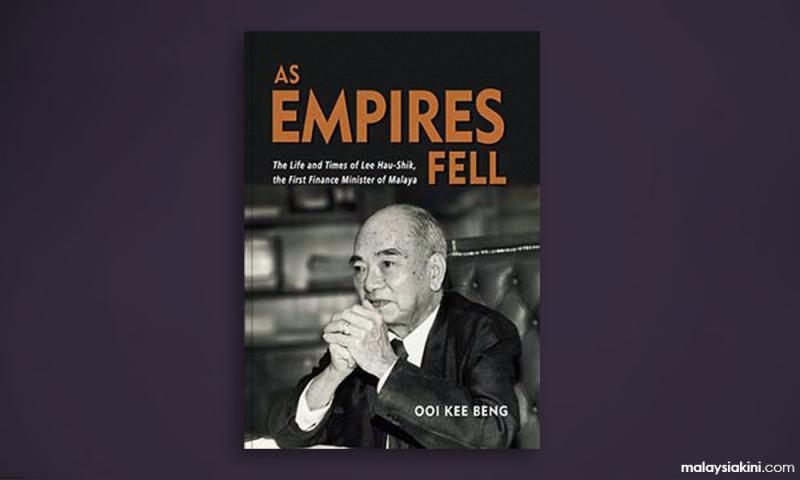

As Empires Fell: The Life and Times of Lee Hau-Shik, the First Finance Minister of Malaysia by Ooi Kee Beng

BOOK REVIEW | There is one particular point that stands out in Ooi Kee Beng’s breezy but complex history of the life of (Henry) Lee Hau-Shik - or more formally Tun Sir Colonel HS Lee, the only foreign-born (and Chinese) signatory of the Malayan Declaration of Independence.

HS Lee does not feature much in the Malaysian popular imagination, even though his life seems tailor-made for intrigue. He was friendly with the future George VI as a student and bon vivant at Cambridge, provided strong links between the business and political elite of China and the colonial administrators of Malaya, was appointed a colonel in both the British and Chinese armies, and eventually became a key founding member of the Malayan Chinese Association (MCA) as the realignment of international geopolitics meant that a new destiny was required for Malaya’s transient and settled Chinese population, then making up almost half of its population.

The genesis of Ooi’s book, written and formulated over several years as he shifted from ISEAS to take up a new role as the executive director of the Penang Institute, began with the examination of 50 boxes of papers provided by the Lee family. What emerged from the research and readings were the details of how a relative outsider, born in Hong Kong and only ending up in Malaya after his separation from his (first) British wife, taking up his aristocratic father’s request that he take over the family’s tin mining interests in what was then the Federated Malay States.

Lee’s rise to political prominence proved accidental, with the onset of the Second World War landing him and his family in India, where, as it turned out, his interests in playing a role in the war led him to the company of the Baba tycoon Tan Cheng Lock and his son Tan Siew Sin, who were both settled outside New Delhi as the war raged. Wartime India also sowed the seeds for the future elite of Malaya, especially since it was a gathering spot for the various “Europeans, Jews, Malay royalty and Chinese” who had escaped to wait out the war.

With his initial efforts to play a deeper role in the Kuomintang’s resistance against the Imperial Japanese Army thwarted, Lee’s politics began to turn towards Southeast Asia. The Tans would go on to start the Overseas Chinese Association during the war years, which despite its name was heavily dominated by Malayan Chinese elites. Despite Lee’s initial contact with the Tans being “rather tense”, and being opposed to the association, their paths would soon cross again.

Post-war Malaya proved to be complicated, and Ooi deftly weaves together the developing strands of history - the brewing Cold War, the rise of the Communist Party of Malaya and the leftist and nationalist movements, the rapid collapse of the British Empire and the unexpected question of what independence, if obtained, would look like.

Chinese capitalist class

This brings us to a point of controversy as to who exactly the real founder(s) of the MCA were.

Officiated in 1949 at the Iversen-designed Chinese Assembly Hall in Kuala Lumpur, Lee and Tan’s paths crossed once more. This time Lee was the director and president of various business concerns, with a firm understanding of the nuances of finance and economics, while Tan’s political activity had continued in earnest, notably playing a key role in the relatively leftist AMCJA-Putera alliance, which sought a more progressive outlook for a colony that was being constructed much in line with the wishes of the newly formed Umno and the aristocracy.

In Ooi’s analysis, Lee was very much a strongman who commanded the interests of the Chinese capitalist class, with Tan being “persuaded” to serve as the president. In fact, Lee was at least partly responsible for brokering the MCA’s political alliance with Umno, laying the foundations for the modern Malaysian political narrative. Seen through these lens, Lee’s control of the Selangor branch of the MCA was a key aspect of his rise to become the first finance minister of Malaya, as the MCA began to transform into a political party.

With all things considered, Lee proved to be a conservative albeit astute minister, balancing the concerns of rural development against defensive spending on the so-called Emergency, even as he lost his chairmanship of the Selangor branch in the lead-up to Merdeka.

After retirement, he would leave politics behind and immerse himself in banking and finance, where he was arguably a much better player, always remembering to enjoy golf, alcohol and other pleasures until his death in 1988 following complications from an operation. His funeral procession went past his favourite streets in the city, the National Museum held an exhibition in his honour, and one of the streets was named for him. Such was the life of this accidental politician.

What Ooi does particularly well in this book is how he ties together the myriad threads of Malaysian history, the nuances of which are often lost in most publications in just 206 pages. He brings in seemingly disparate topics ranging from the Indonesian revolution, opium revenue, the Kuomintang’s covert presence in Malaya, the pre- and post-war leftist movements and the life of an individual into a coherent story.

But this is not a narrative about how one man changed the fate of a country, but rather it departs from the “great man theory” to show how quite often, one gets caught up in history through the accidents of time and place. One does not necessarily shape history, but rather, one is shaped by it. It is also a closer look at the evolving identity and politics of the Chinese Malaysians as they changed over time, and provides a better understanding of where exactly we are today.

Suggested reading

Loh, KS, Seng, Guo-Quan, Lim, Cheng Tju and Liao, Edgar (2012). ‘The University Socialist Club and the Contest for Malaya: Tangled Strands of Modernity’. Amsterdam University Press, Amsterdam.

Ooi, Kee Beng (2007). ‘The Reluctant Politician: Tun Dr Ismail and His Time’. ISEAS, Singapore.

Show, Ying Xin and Ngoi, Guat Peng (eds) (2020). ‘Revisiting Malaya: Uncovering Historical and Political Thoughts in Nusantara’. SIRD, Petaling Jaya. Upcoming.

Syed Husin Ali, Ariffin Omar, Jeyakumar Devaraj and Fahmi Reza (2017). ‘The People’s Constitutional Proposals for Malaya’. SIRD, Petaling Jaya.

Yong CF and McKenna, RB (1990). ‘The Kuomintang Movement in British Malaya’, 1912-1949. University of Hawaii Press, Honolulu.

WILLIAM THAM WAI LIANG is an editor at Gerakbudaya and the author of two novels. His first book, ‘Kings of Petaling Street’, was shortlisted for the Penang Monthly Book Prize in 2017. His new novel, ‘The Last Days’, is set in 1981 and covers the continuing legacy of the Emergency.

RM12.50 / month

- Unlimited access to award-winning journalism

- Comment and share your opinions on all our articles

- Gift interesting stories to your friends

- Tax deductable

William Tham Wai Liang

William Tham Wai Liang