COMMENT | Is unity government realistic or desirable?

COMMENT | After the seeming defeat of Anwar Ibrahim in the race for prime ministership, the idea of a unity government has been raised by two prominent persons.

First, DAP veteran leader Lim Kit Siang suggested Anwar be made deputy prime minister to Ismail Sabri Yaakob, the presumed winner. Next, civil society leader Ambiga Sreenevasan started a petition to call for a unity government.

Like many ideas floated as a solution to the political stalemate and instability, the intention for a unity government is noble. But nobility in intention does not guarantee realism of plan and desirability of outcome.

So, is it realistic and desirable? Most of all, is it “the only way forward” to end instability as asserted in Ambiga’s petition?

Models of success: wartime cabinet and BN

The commonly drawn comparison to support the call for unity government is a wartime cabinet, which includes all parties and has an overarching goal: winning the war.

In Malaysia, many would also think of the post-1969 coalition governments – at the federal, state, and municipality levels - which later transformed into the Barisan Nasional in 1974 as a model of unity government.

What makes the idea of wartime cabinet and BN successful?

In a wartime cabinet, foreign occupation presents an imminent threat that applies equal pressure to all parties. No elections as a sovereign state can be held if the country is lost.

In the BN case, Tun Razak’s strong will to minimise political competition using the prospect of future riots and his vast power under and even after the Emergency left SUPP, Gerakan, PPP, and PAS with little choice than accepting his “power-sharing” offer.

Many analogise the Covid-19 as a common enemy to all parties. But unlike the threat of foreign occupation, the virus does not make all parties equally worse off. Whatever the damage, the all-out war against Covid-19 would be over or downgraded sometime, and some parties would be better off while others worse off in the subsequent election.

This poses a challenge to an anti-Covid-19 unity government: how to even out its benefits across parties and how to spread out the cost of not having one to all parties?

On the Perikatan Nasional-BN side, so far only Umno Youth chief Asyraf Wadji Marzuki has talked about “a cabinet capable of translating the consensus and unity of all political parties”.

If unity government is viewed as a demand to benefit the opposition, which notably did not moot such idea when the race was still open, will PN-BN-GPS++ (hereafter the government) accept it?

A bloated cabinet to ease buy-in?

One way to make unity government more acceptable for politicians is to have a bloated administration so that the presumed winners can keep most of their eyed ministerial portfolios while some can still be given to the presumed losers.

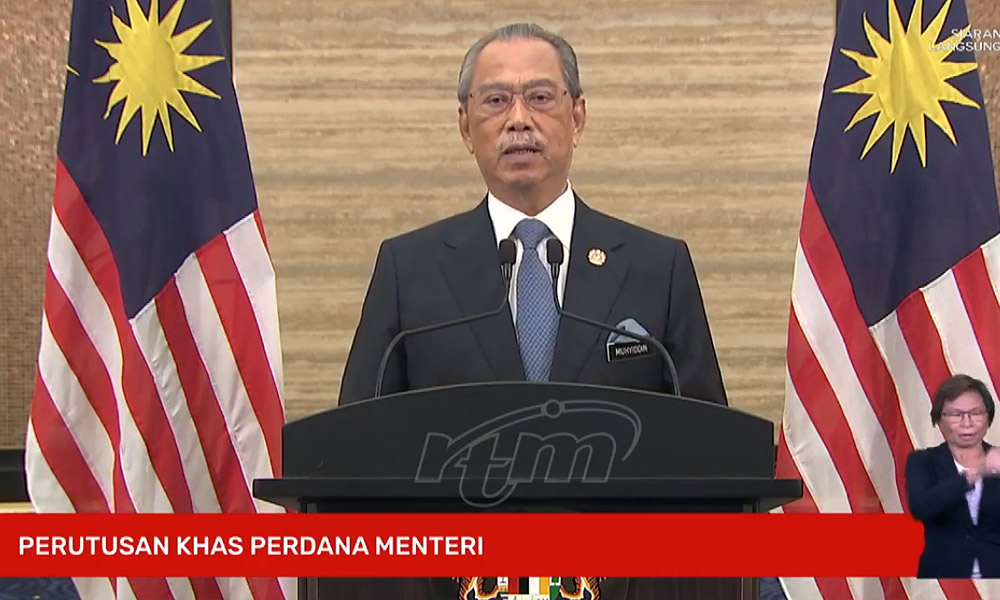

Muhyiddin’s administration had 36 ministers and minister-level convoys/advisers and 37 deputy ministers, totalling 73. Excluding the eight senators, 63 or 55 percent of 115 government MPs had an executive job.

Creating ministerial jobs was, of course, Muhyiddin’s way of building a Malay unity government, which still failed eventually. But the public will not accept an even more bloated government than Muhyiddin’s.

Ambiga’s petition indeed demands a smaller cabinet that reflects a “sense of purpose”, that is, no buying of political support with ministerial jobs. Good idea.

Let’s operationalise and get down to numbers. First, scale down the administration to only 55 ministers and deputy ministers, the benchmark set by Pakatan Harapan. Second, since the government and opposition had a parliamentarian ratio of 115:105, split the 50 by a ratio of 6:4, the government will get 33 while the opposition will get 22.

This means 30 government MPs who were former ministers and deputy ministers would lose jobs. How strongly will the government parties and MPs resist it? How long will it take for negotiations and announcement of the full cabinet?

Infighting within the unity government?

Because Ismail Sabri is so weak, if a unity government is strongly demanded by the palace and the public, it may indeed happen.

However, will this end the interparty fights, both between and within the government and opposition camps?

With so little trust between the parties, can the ministers work professionally with each other in the cabinet and with their deputy ministers from other parties within each ministry?

Remember the power struggle over movement control order measures between two senior ministers Ismail Sabri and Azmin Ali in Muhyiddin’s last month? Now, imagine this happening between a PAS minister and a DAP minister, or a Bersatu minister and a PKR minister.

Next, if a DAP/PKR backbencher criticises a PAS/Bersatu minister, or vice versa a PAS/Bersatu backbencher criticises a Bersatu/PAS minister, will this be hailed legislative oversight or slammed as partisan potshot?

To maintain 'unity' and 'peace' in the unity government, should the remaining 170 government backbenchers (remember, no opposition MPs if the unity government engulfs all parties) exercise restraint to ensure harmony and love in the Dewan Rakyat?

I support the petition’s idea to let the new government run full term because sound pandemic and economic policies cannot have short shelf lives in a matter of months.

However, if a ‘national unity government’ means inter-ministerial power struggles or restraining of parliamentary oversight to maintain peace, will it do better than Muhyiddin’s ‘Malay unity government’?

Unity or healthy competition?

Undisputedly, we need multipartisan governance to better save lives and livelihood. But unity government is certainly not “the only way forward”.

Unity government is based on the old paradigm that collective goals can only be achieved by putting everyone in one team, no matter how incompatible they may be with each other. This paradigm also sees majority government as an absolute necessity.

In the extreme form, interparty competition should be eliminated if all parties can form an electoral cartel – yes, like the big happy family that the old BN wished to be.

The alternative is the paradigm of healthy competition, check and balance and professionalised politics.

Governments should consist of only coherent parties and ministers who can work professionally with each other. Other parties and parliamentarians can provide professional check and balance to the government without being nasty.

Governments need not have their own majority but if they don’t, they enter Confidence and Supply Agreements (CSAs) to negotiate conditional support.

The best example is New Zealand, where Prime Minister Jacinda Adern superbly managed the pandemic in 2020 when running a minority coalition government on a CSA with the green party.

Let’s move on from World War II or the post-1969 aftermath in improving our present and future.

What the new government should do is to sign CSAs with various opposition parties to protect its lifespan from any threat of pullout.

The CSAs should go beyond Muhyiddin’s seven-point offer, and Bersih 2.0, Muslim Youth Movement of Malaysia (Abim), Gabungan Bertindak Malaysia (GBM), and Kuala Lumpur and Selangor Chinese Assembly Hall (KLSCAH) have offered a comprehensive 10-point “cross-party political stability pact”.

Two of them are worth elaborated here as alternatives to unity government.

First, a thorough reform of Parliament, making it the arena where government and opposition compete and collaborate professionally on policy and governance, where every ministry would be scrutinised by a Parliamentary Special Select Committee (PSSC) and every MP who is not a minister or deputy minister gets to sit on at least one PSSC to scrutinise the government.

Second, setting a Federal-State Council (FSC) on Health and Economy, chaired by the prime minister with the parliamentary opposition leader as the deputy, consisting of key ministers, senior opposition MPs, and chief ministers from all 13 states. This can remedy over-centralisation of policymaking that has hindered state governments’ opinions and resources in the formulation and implementation of pandemic policies.

The 13,000 lives lost are a strong reminder that our political system is broken and needs to be fixed. But in finding solutions to fix our system, let’s be always conscious of “unintended consequences”. As they say, “the road to Hell is paved with good intentions”.

WONG CHIN HUAT is an Essex-trained political scientist working on political institutions and group conflicts. Mindful of humans' self-interest motivation while pursuing a better world, he is a principled opportunist.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of Malaysiakini.

RM12.50 / month

- Unlimited access to award-winning journalism

- Comment and share your opinions on all our articles

- Gift interesting stories to your friends

- Tax deductable

Wong Chin Huat

Wong Chin Huat