COMMENT | Preventing children from becoming parrots as they learn to read

COMMENT | “Parrot phenomenon” is the name given to one of the more persistent problems with literacy.

Many times, a child can sound out or mimic the words on a page but, like a trained bird, is unable to comprehend the meaning of the words and sentences.

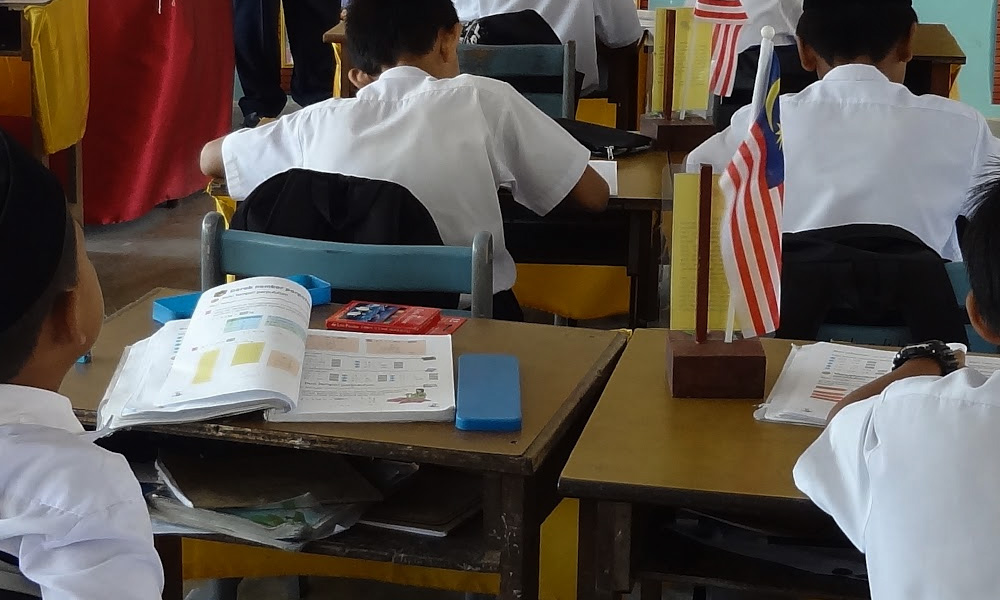

In Malaysia, the parrot phenomenon is particularly prevalent among children who are not in a literacy-rich environment and whose socioeconomic background is lower-than-average, including rural school children from a B40 household, which is in the bottom 40th percentile, earning less than RM4,850 per month (US$1,021).

But approaching literacy with the same tools that cause this phenomenon will not contribute to its solution. Instead, new ideas from teaching theory need to be considered.

In Malaysia, barring some exceptions, the phonics approach – associating shapes with sounds — is central to teaching literacy in English and Malay.

Currently, our literacy rate stands at 95 percent among 15 years and older, and 77.2 percent among 65 years and older.

Regardless of the type of writing system, whether logographic (for example Mandarin) or non-logographic (for example English, Malay), the aim of literacy is for the learner to be able to demonstrate the ability to turn writing symbols into sounds.

Among the main reasons for the parrot phenomenon is the lack of support working together across home, school, and community to ensure meaningful literacy.

School becomes the only place for these children to learn how to read.

If children’s experience of literacy is the mechanics and functions of reading and less about reading for pleasure, it reduces comprehension.

This underscores why a new focus on what is called “meaningful meaning-making” is important to transform reading from being merely functional into something that is essentially intertwined with being human.

Multiple methods to teach reading

One way to achieve better meaning-making is to broaden the definition of reading and literacy, particularly in how it is understood, taught, and practised in Malaysia.

Underpinning this is theories of literacy that argue that there are multiple methods to teach reading.

This perspective uses creative methods like pictures, sounds, and texture to create situations appropriate to the socio-cultural and even socioeconomic environment of the learners so that reading becomes more than a skill to be learnt.

For example, while wordless picture books are commonly used in schools in other parts of the world, they are less common in Malaysian schools and homes.

The singular focus on learning how to read in its linguistic form leaves little room for non-linguistic, non-written forms to be explored.

Those who struggle to make meaning through the conventional alphabetic-centric method of writing would be able to access other symbolic systems that can become alternatives for making meaning.

Providing both pictorial and written symbolism can be especially crucial for new readers because the combination of both stimuli can allow the one that resonates more strongly to be used as the primary meaning-making tool, acting as a bridge to better comprehension.

However, an unconventional method of teaching literacy raises questions about how reading skills are measured and assessed: how will a teacher know if a child can read?

Before high-stakes reading level testing, sufficient encouragement could be given to learners to establish meaning-making through alternative means.

And it is important to acknowledge that generalising learning across all learners does not help build lifelong readers.

As the struggle to ensure universal literacy continues, the next few decades will require a more critical, transformational approach to raising generations of not only literate children but meaningful meaning-makers.

New literacy spaces are one way forward.

SU LI CHONG is a senior lecturer at the Department of Management and Humanities, Institute of Self Sustainable Building, Universiti Teknologi Petronas (UTP), Malaysia. She is also Head of UTP’s University Social Responsibility (Education Pillar). She obtained her PhD in Education from the University of Cambridge, UK. She tweets @chongsuli

Originally published under Creative Commons by 360info™.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of Malaysiakini.

RM12.50 / month

- Unlimited access to award-winning journalism

- Comment and share your opinions on all our articles

- Gift interesting stories to your friends

- Tax deductable