Entrenched reasons to fuss over khat

LETTER | In Indonesia, the assimilation policy under the New Order repressed Chinese culture.

The Chinese there were forced to adopt Indonesian-sounding names, their schools and publications were shut down and expressions of Chinese culture and language became illegal.

In Singapore, since the 19th century, vernacular education started with limited assistance from the British colonial government.

After independence, enrolment dwindled. By 1987, all schools taught English as a first language.

True, there are Chinese schools now, but the 26 Special Assistance schools are periodically criticised by Singaporeans for ethnic segregation it inevitably promotes and a reputation of being the "elite" group of secondary schools.

In Malaya, initially, the colonial government did not provide for any Malay-language secondary schools, forcing students to adjust to an English-language education.

As a remedy, they established the Malay College Kuala Kangsar. However, it was never intended to prepare students for entrance to higher institutions but to educate low-level civil servants.

After 1957, Chinese secondary schools were given the option of accepting government funding and change to English national-type schools or remain private without government funding.

Most of the schools accepted the change, although a few rejected the offer, and came to be known as Chinese Independent High Schools.

Shortly after the change, some of the national-type schools reestablished their Chinese independent high school branches.

The Razak Report — a compromise between the Barnes Report (favoured by the Malays) and the Fenn-Wu Report (favoured by the Chinese and Indians) — called for a national school system consisting of Malay, English, Chinese and Tamil-medium at the primary level, and Malay and English-medium at the secondary level, with a uniform national curriculum.

After 1961, only 14 Chinese secondary schools remained "independent" schools because they wanted to keep their mother tongue system at all costs.

This division has been criticised for allegedly creating racial polarisation at an early age, similar to ethnic segregation in Singapore.

As a solution, attempts were made to establish Sekolah Wawasan — three schools (one Sekolah Kebangsaan (SK), one SJK(C) and one SJK(T)) would share the same school compound and facilities with different school administrations.

However, this was met with objections as it was believed this would restrict the use of their mother tongue.

Championing this cause is Dong Zong.

Since its inception in 1954, Dong Zong worked closely with the Chinese Association of Chinese School Teachers (Jiao Zong) in championing Chinese rights.

Dong Zong wants to uphold the education of the mother tongue while demanding justice and equality of status and position among all races or ethnic groups and promote harmony and unity among the people.

Students sit for the Unified Examination Certificate (UEC). A few schools cater for students taking the government's Sijil Tinggi Pelajaran Malaysia (STPM).

The argument against accepting the UEC is over the subject of History and Bahasa Melayu (BM).

UEC has been accepted by international universities but Malaysia rejects it on grounds that its history syllabus does not contain “adequate” local content.

It is also said that both the UEC and the national curriculum are flawed in their understanding of history in a narrow construct.

BM is a non-issue since most public universities, except for two or three lectures and assignments are in English.

It was highlighted that US colleges and universities were the first institutions to recognise the UEC and thousands of UEC students have graduated and employed in foreign countries.

Also, our country will remain divided if the graduates are denied the opportunity to participate in nation-building and national integration by being refused admission into our tertiary institutions, civil and armed services and GLCs.

Recognising the UEC will help to promote greater integration and also alleviate the financial plight of the graduates who cannot afford tertiary education in private colleges or abroad.

Further, there are hundreds of non-Chinese students in independent Chinese secondary schools and almost 100,000 in Chinese primary schools.

Also, the Pakatan Harapan manifesto pledged to recognise the UEC as part of reform in a new and inclusive Malaysia. Pussyfooting and backtracking is not an option and is considered patent dishonesty.

But how about the many Chinese students who follow the system and are in national schools?

They will be disadvantaged with the influx of those who earlier chose not to follow the system.

Surely, we also do not want to be known as people who do things first and worry about authority approvals or acceptance later.

Separately, SK is seen as resembling religious or Islamic schools for insistence on the Islamic dress code, the reading of Muslim prayers during events and assembly.

It frightens non-Malay and non-Muslim parents away from public schools.

To be fair, Putrajaya directly allocated millions to upgrade Chinese independent schools and non-profit private colleges that cater to Chinese students.

Opposition parties criticised it as giving funds for something that is not in line with the national policy and spirit. It also angered parents whose children go to dilapidated national schools. Is this justice?

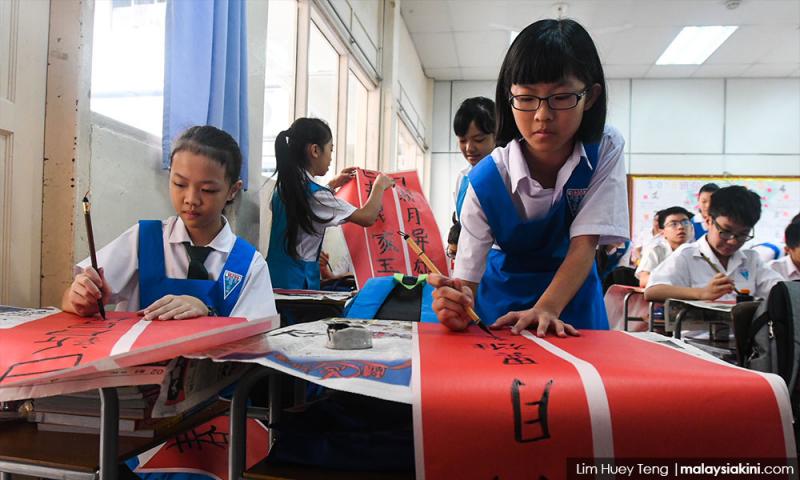

Khat, like Chinese calligraphy, is a kind of visual art. The style of writing is called script, or letter (Fraser and Kwiatkowski 2006; Johnston 1909: Plate 6). Tracing, copying the Jawi characters and adding the dots produces khat calligraphy.

True, there were more important issues to be tackled by the Education Ministry, like preparing pupils to be more competitive than introducing khat.

But all that is required of Year Four pupils in vernacular schools is the subject would only be taught four times a year for 10 minutes as support material for the BM syllabus. Only five to six Jawi characters would be introduced.

Jawi is an Arabic script for writing Malay, Acehnese, Banjarese, Minangkabau, Tausūg and several other languages.

It used to be the standard script for the Malay language and was a key factor driving the emergence of Malay as the lingua franca of the region. Jawi script is protected by Section 9 of the National Language Act 1963/67.

Despite protests on the teaching of Jawi writing in vernacular schools, the High Court in Penang decided that the teaching of the Jawi writing was part of Bahasa Malaysia and could be taught in Chinese and Tamil schools.

Further, khat is part of the Standard-Based Curriculum for Primary Schools (KSSR) syllabus that was reviewed in 2014 and implemented in 2017. The KSSR implementation (for vernacular schools) was set for next year.

Dong Zong will be chairing a meeting on Dec 28 with Chinese associations to protest the implementation of khat.

It rejected Jawi script as they circumvent the authority of school boards in deciding school policies and sow disharmony among parents and students.

Under the new guidelines, the module is to be implemented if 51 percent or more parents at a school agree to it.

The cabinet decided not to involve the school boards for khat and parents, as guardians, as the main decision-making body. Just like the dual language programme, one of the criteria was parents’ requests.

I am not sure how it will sow disharmony among parents and students if parents are included in the decision-making process.

It makes more sense since there are close to 100,000 non-Chinese in these schools and khat is part of the Malay heritage and has aesthetic value. Out of 1,300 Chinese vernacular schools in Malaysia, 600 have fewer than 150 students, many of whom are of non-Chinese descent.

Justice has to be shown here, too, similar to the request for participation in nation-building and national integration.

The creation of choices in the Malaysian education system is unique and provides an unparalleled degree of choice for parents and students. This variety is a result of the nation’s historical legacy, rich diversity and compromise.

Thankfully, Malaysia did not force like our neighbours did but gave options and came to a compromise.

You can't have your cake and eat it while demanding justice and equality and to promote harmony and unity among the people.

For the government, there should be more engagements with relevant stakeholders.

I love Confucianist cultural heritage which emphasise values such as hard work, education, family unity, deference and loyalty to authority figures, among others.

Let us all practice it and as Finance Minister Lim Guan Eng had said, “I’m Malaysian, not Chinese.”

What say you?

Seasons greetings to all Malaysians at home and abroad.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of Malaysiakini.

RM12.50 / month

- Unlimited access to award-winning journalism

- Comment and share your opinions on all our articles

- Gift interesting stories to your friends

- Tax deductable