LETTER | The uncomfortable reality of abuse in our schools

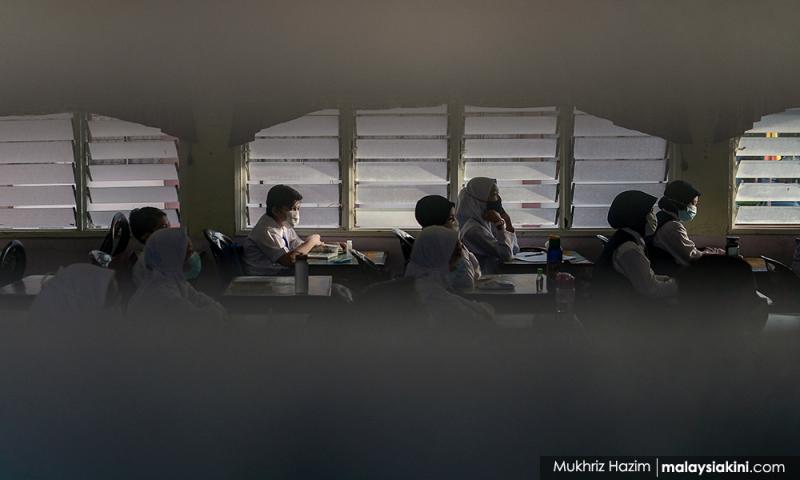

LETTER | Recently, broadcaster Awani ran an interview with the National Union of the Teaching Profession secretary-general Harry Tan and his response to allegations of abuse in Malaysian schools. His immediate response, followed later by an apology and clarification, perfectly captured the bewilderment that many, especially those who are or were teachers, have experienced at the recent revelation that sexual harassment, abuse, and rape culture have existed in our schools, possibly for decades.

Tan’s demand for evidence, statistics, details, and descriptions particularly in the form of police reports of such incidents occurring in schools, was clearly a knee-jerk defensive response which he later regretted. However, while the demands were indignant, they were valid and necessary for us to fully understand the depth, scale, and seriousness of the problem being confronted.

Evidence and data are needed in order to be taken seriously. In response, someone took the initiative and decided to compile stories based on the experience of former and current survivors, encouraging them to submit their experiences online. The result is an Instagram page, savetheschoolsmy, that has documented and uploaded 250 stories so far. For many, these anecdotes make for harrowing reading, and for others, it brings back unpleasant and even traumatic memories.

The possibility that many of our schools could be unsafe environments for our children is a terrifying reality. That we have overlooked, been ignorant of, or even deliberately ignored such incidents. That we have allowed them to happen, hiding behind the formality of needing a police report.

Three decades ago, I wondered why the girls in my school were sometimes held back after general assembly. I later found out that it was to allow teachers to check that the students were wearing the right type and colour of panties and bra. No such humiliations were meted to boys and their underwear.

During religious classes, to be permitted to be excluded from prayers at the surau, girls were told to show proof that they were menstruating. I never knew what proof was demanded but remember thinking that was a ridiculous demand. Why force people to prove they could not pray? For some reason, male teachers including those who taught religious classes and physical education, thought it was acceptable to crack vulgar jokes and often sexual innuendo, especially to female students.

Now, we have hundreds of stories from hundreds of women and girls, sharing their experiences, the abuse they suffered, and the trauma they lived through. It has ranged from period shaming, sexual harassment to tolerance of rape culture and molestation. The anecdotes stretch for decades.

Let us be honest. As students, parents, and teachers, we have always known that these incidents, behaviour, and occurrences existed. We just did not think they were wrong. Perhaps, we were not paying attention.

Somehow, generations of students and teachers have gone through similar experiences. They are not isolated incidents. It might have happened to your daughter or even to you. The hundreds of stories tell us of widespread institutional failure.

There will be many women and even men who will say today that they were able to cope or deal with what they went through back in school. That they have grown up and become successful, without the need to seek help or get therapy, make reports, or lodge a complaint, but that would be besides the point. These abuses should never have happened, could have been prevented, and the environment should never have permitted for such behaviours to be condoned, tolerated, and continued.

The fact that grown women and men are still able to recount in detail what happened to them or what they experienced either from several years or decades ago, speaks volumes to the kind of potential damage or lasting trauma that could be inflicted.

Due to the courage of students such as Ain Husniza and social activist Nalisa Alia Amin sharing their experiences and those of others, this past month has seen a bright spotlight being shone onto this long-neglected issue in our education system.

It is shocking but a lot of work needs to be done.

Teachers and administrators are figures of authority and respect in school structures. Educators represent more than just someone who provides an education and learning experience for students. They are also those who are entrusted with the safety and wellbeing of individuals who are at a formative stage of their lives. It is often a thankless job which several members of my own extended family can testify to.

To help them do their work and to ensure that they are able to protect students and safeguard against misdemeanour, harassment, and abuse, even if it is from among their own colleagues, there must be clear guidelines, procedures, and policies.

The Ministry of Education must work with the Ministry of Women, Family and Community Development to ensure a Child Protection Policy which also covers the public education system. It is clear that the existing National Child Protection Policy 2009 is inadequate and needs to be updated to include what we have now learned. Definitions of abuse and sexual harassment must be revised, procedures put into place, and codes of conduct introduced. The Sexual Harassment Bill must become law.

The government should also not exclude itself from implementation and enforcement of the said policy, including the Child Act 2001. What it imposes on the private sector should also be applicable to the schools under the Ministry of Education.

A sensitisation programme on sexual harassment and rape culture should be introduced throughout the public education system, focusing on awareness, prevention, and response. This should be a required course for all teachers, both men and women, regardless of their seniority. It is obvious that we need that done today.

Being a female teacher does not mean that abuse or harassment of girls does not happen, especially when the behaviour is not recognised or acknowledged as such. Those teaching religious studies should not be given a pass on these issues, especially since opportunities for period shaming have occurred within that context.

These reforms are clearly long overdue.

It goes without saying that we need to create safe environments for our students. These revelations have cast a shadow on Malaysia’s education system which we continue to be proud of. However, in our race to achieve academic excellence and to produce scientists, engineers, diplomats, doctors, artists, and writers, we have somehow neglected our children’s wellbeing, mental health, and safety.

Moving forward, we must recognise that we have a serious problem on our hands, work together on the solutions, and do better for our daughters and sons who depend on us to keep them safe and away from harm.

AZRUL MOHD KHALIB is the head of Galen Centre for Health & Social Policy.

The centre is an independent public policy research and advocacy organisation based in Malaysia that is dedicated to discussing health and social issues through the lens of public policy. The full declaration of the 31 global think tanks can be seen at the Galen Centre website.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of Malaysiakini.

RM12.50 / month

- Unlimited access to award-winning journalism

- Comment and share your opinions on all our articles

- Gift interesting stories to your friends

- Tax deductable