LETTER | Death in custody - the questions of concern

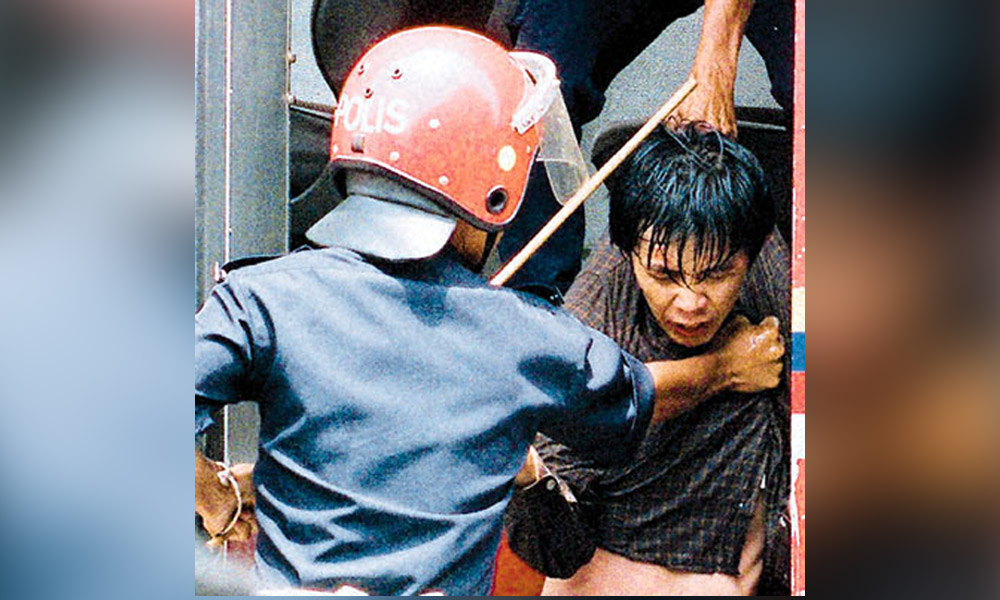

LETTER | It seems now that we are back to the death in custody (DIC) season with four deaths since the April 18 death of A Ganapathy. These are just the "lucky" ones because their cases got reported and highlighted. Compared to previous DIC cases, what is different this time around, is the huge public outcry Ganapathy’s death generated on social media.

My first exposure to DIC was 25 years ago, when an air-conditioning mechanic Lee Quat Leong, 42, died on May 12, 1995, after two weeks in police custody. The death certificate stated the cause of death as "haemorrhage consistent with blunt trauma to most parts of the body".

The late Karpal Singh was the lawyer then and said that there were numerous injuries and fractures on the victim’s body - on a person who was healthy at arrest and had no previous police records. There was some public reaction to his death resulting in the police conducting an internal investigation. The internal investigation result was that they were unable to identify Lee’s assaulters.

The attorney-general then, Mohtar Abdullah, on Oct 10, 1995, ordered a judicial inquiry after the police failed four times to identify the perpetrators. This was my first exposure to death in detention. It was also my earliest exposure to police abuse and cover-up.

The inquest finally found 11 policemen responsible for Lee's death. Although the inquest implicated 11 policemen, including some of the higher rank of ASP, only two low ranking policemen were finally charged. The two were charged under a much lower charge of "causing hurt" when in fact an innocent man was murdered in police custody.

Both low-ranking policemen pleaded guilty before the Sessions Court for a charge under Section 330 of the Penal Code for "voluntarily causing hurt". The "blunt objects or weapons" mentioned in the post-mortem report were not tendered as exhibits in the trial. They were each sentenced to just 18 months in jail.

People were not happy with the verdict and pressure piled up on the government to appeal this decision, but it was rejected by the AG. Lee’s family and Karpal did not give up. The brother of the victim applied for the sentence to be reviewed and the matter was brought up to the High Court.

At the review stage in the High Court, the public prosecutor argued against a heavier sentence. But KC Vohrah, a highly principled judge, doubled the sentence against the two policemen. Passing judgment, he said: “Police officers are custodians of the law and they have to uphold, not breach, the law.”

Now that was more than 25 years ago. That wasn’t the first DIC, case definitely, but one that got massive publicity resulting in some form of justice. Has anything changed since then? There are some issues that keep popping up each time death in custody occurs. Here, I try to address some of these issues.

Is death in custody wrong?

The fundamental question is, is DIC right or wrong? Now, without checking what is the ethnicity or religion of the deceased, I am sure everyone will have a common position that DIC is wrong.

Why is it wrong? When someone is arrested and put in custody, it is the role of the person taking care of them to ensure their safety and well-being.

All of our laws, from the Federal Constitution to the Penal Code, and the Human Rights declaration, clearly spell out that DIC is a crime and cannot be justified. Article 5 of the Constitution talks about the right to life.

Do DIC victims deserve it?

One question which arises each time there is a DIC is the view by some that these people deserve it. Even if the person who died is presumed a bad person, having committed many offences before, is his death justified? Some even call it karma while others say it is the law of nature. Here again, how do we justify karma? Does it mean all the people who died of Covid-19, or are born with a disability, are just paying for their past sins?

It is because of all these questionable positions that one has to always rely on the notion that everyone is innocent until proven guilty. People have asked us before why we are protecting these “criminals” and that we will only understand if our loved ones were the victims of their crimes. Similarly, we can also argue that the dead person also needs justice and one would only understand if the person who died in custody is their own family member.

So either way, the best way to go about this is to let the law decide on this and to always give the benefit of the doubt. Innocent until proven guilty is a crucial fundamental principle, which gives each person involved, including the police and authorities, an opportunity to prove their innocence.

Another angle to the question is even if the person has committed an offence, does he or she deserve the death sentence? Death sentences are only for limited offences in Malaysia such as murder, drug trafficking, treason and acts of terrorism. Most of the victims of DIC are just suspects of lesser crimes.

Are Indian Malaysians the target of death in custody?

Now, is DIC about Indians? Statistically, more Malays die in custody compared to Indians and then followed by Chinese. But if we go by population, the ratio of Indians dying in DIC is much larger than the other ethnic groups.

Based on official figures, Malays make up the majority of victims who die in police custody, 42.4 percent, compared to Indians at 23.4 percent, followed by others 18.3 percent and Chinese 12.3 percent.

Why do Indians say or feel that they are targeted? Based on the 2019 population estimates by the Statistics Department, Indians only comprise 6.85 percent of the population which means the ratio of death in custody is three times higher than their population.

If we go by reported cases, of cases that become highlighted and notorious, then the analysis done by Suaram during this period shows that the nationwide coverage of DIC was 54.8 percent for Indians and only 17.7 percent for Malays. There are many reasons for this. For one, only one in four cases become public knowledge. Besides that, there are cultural and religious reasons how different communities and ethnic groups deal with death.

To understand the high proportion of why Indians are seen as targets, we need to patiently look at other statistics. However we look at this, the Indians ratio proportionately are higher in crime statistics, in prisons as well in social indicators.

The percentage of Indians in prison is close to 10 percent (9.82 percent) based on Prison Department records in 2019. According to the Science and Wellness Organisation (SWO), a non-profit organisation, Indians make up 72 percent of the total gang members in Malaysia.

Bukit Aman Secret Societies, Gambling and Vice Division (D7) statistics as of March 2018, put Indian active gang members at 47 percent, which is the highest of all the ethnic groups.

The crime of poverty

We need to distinguish between symptoms and causes. There is definitely a direct link between the social ills in the Indian community and the Indians ratio is disproportionately a high ratio of deaths in custody. We cannot see this in isolation as well.

Can we generalise this problem for all Indian Malaysians? Definitely not. Rich and prominent Indians like Anantha Krishnan, Tony Fernandes and G Gnanalingam, don’t die in custody because there is something called the class element in this issue.

Many link the large number of Indian gangs to issues such as high school dropout rate, unemployment and poverty. These are social issues that need to be addressed. Some of these figures are alarming. It is said that four in 10 Indian youths drop out from school, and yearly 10,000 students leave school before completing their SPM for various reasons, and pertinent reasons for this are the inability to afford schooling and to move into the job market.

Thirteen percent of the total number of school dropouts from primary school are also Indians. The same NGO also reported the passing rate of Indians for SPM is only five percent compared to the national average rate of 55 percent.

If you go into unemployment the Indian ratio is also high. The unemployment rate among male Indians is four percent compared to the national male unemployment rate of 2.9 percent, and for female, it is 5.2 percent compared to the national female unemployment average of 3.2 percent.

Institutional discrimination

So while I take the position that DIC is solely not an Indian per se issue and that it happens across the board, we cannot also completely shut our eyes to other contributing factors.

In Malaysia, because affirmative action policies are not based on need, there is a tendency to reinforce the divide-and-rule policies; to keep people apart and rule by communal and not class lines.

Institutional racism does exist in Malaysia and most political parties, politicians, policies and laws may have such discriminatory tendencies. Some discrimination is called for: positive discrimination whereby if you are poor you get helped more, if you are disabled, you get more privileges.

This is good and we must support it. But there are discriminatory policies that we need to oppose. Similarly, in assisting and uplifting marginalised communities, discrimination should be based on needs and not ethnicity.

We all need to deal with the issue of discrimination. Now the issue of some groups highlighting death in custody incidents in a racial manner can be explained and understood. But it cannot, in any way, be stretched to say that the police systematically target and kill Indians in the lock-ups. This accusation is outrageous and farfetched.

In the many cases I have handled, police torture, misuse of power and negligence is real. The truth is every ethnic group faces the same police brutality. We can give you evidence on how non-Indians die because of torture and negligence as well.

It is also not surprising, and true that in many cases the ethnicity of the perpetrator is the same as that of the victim. I remember handling the case of a young Malay boy near Banting who was badly bashed up by a Malay police officer.

Also, while monitoring DIC cases in court, we find Indian policemen being the biggest abusers of Indians in custody. I remember Tian Chua being assaulted by a Chinese man when he was in custody.

So I came up with my own hypothesis that perpetrators from the same ethnic group inflict more torture on victims from the same ethnic group because they believe they have some “moral responsibility” to their own community.

Black lives matter

Most Malaysians from all walks of life have been generally very supportive of the Black Lives Matter movement in the US. The success of the movement is reflected not in how many blacks come to the streets, but in how many whites stand against racism.

Similarly, if Indian NGOs want to see success in the death in custody campaign, it is not how many Indians unite and protest but how many non-Indians participate and struggle against death in custody.

In the Ganapathy DIC case, the response from non-Indians critiquing the death was very welcome and refreshing. This is what we need to build. We need to unite all Malaysians to oppose DIC and to push for higher universal human rights values.

Indians who raise this issue must also be objective and inclusive in getting the understanding and involvement of different communities, and themselves get involved when non-Indian communities are affected. If this discourse is not done, DIC will always be seen as a narrow racial issue rather than a human rights issue.

DIC in conclusion is not merely a law and order issue. It is an issue with many dimensions and needs to be fought from all angles. We need to fight poverty, racism and DIC together with the same aim - to fight for justice and end discrimination.

Non-Malays have to question Malay poverty, Malays need to question the death in custody of Indians, and so on. Only if we can narrow these perception gaps and clear the smog surrounding the issues, can we deal with the real violation at hand.

S ARUTCHELVAN is deputy chairperson of Parti Sosialis Malaysia (PSM).

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of Malaysiakini.

RM12.50 / month

- Unlimited access to award-winning journalism

- Comment and share your opinions on all our articles

- Gift interesting stories to your friends

- Tax deductable