LETTER | Electoral justice and first-past-the-post system in Malaysia

LETTER | On May 9, 2018, Pakatan Harapan’s victory in the 14th general election (GE14) marked the first democratic change of the federal government in Malaysia.

However, the collapse of the Harapan government, the infamous “Sheraton Move”, and a change in prime ministership three times in just four years seem to suggest that something is wrong with Malaysia’s parliamentary democracy.

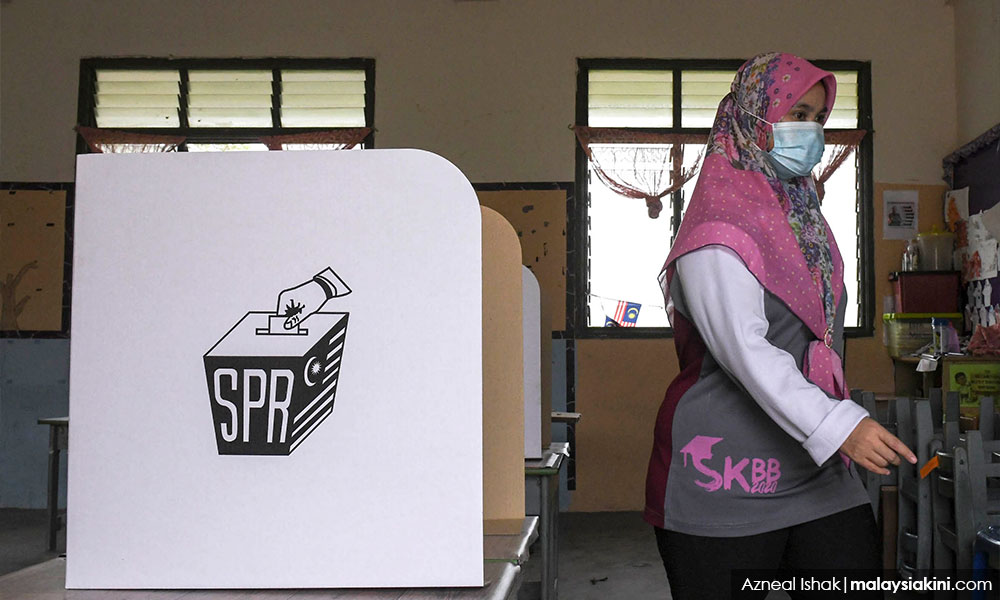

Malaysia practices the first-past-the-post voting system. This system is also commonly known as the “winner-take-all system”. When voters go to the polls, they vote for an MP who will represent their federal constituency for the next five years.

In most states, the state election also takes place at the same time. This means that voters will also be voting for their respective state assemblypersons.

The candidate who wins the most votes in each constituency will win the seat, despite not winning with more than 50 percent of the votes. This became a common situation in a vast number of parliamentary constituencies in Malaysia.

For example, during GE14 in the Ayer Hitam parliamentary seat, BN’s Wee Ka Siong won with only 43.98 percent of the votes, while Harapan’s Liew Chin Tong garnered 43.2 percent, and PAS’ Mardi Marwan gained 12.82 percent of the votes.

In this case, Wee represented all constituents in Ayer Hitam at Parliament.

However, the biggest problem with the first-past-the-post voting system is gerrymandering, which tends to favour the ruling coalition.

For example, in 2018, boundaries were redrawn to pack voters that would most likely vote the opposition into certain constituencies, creating “superseats” that would almost certainly be won by the opposition.

At the same time, a lot more seats with fewer voters have been created that favour the ruling coalition.

This brings up the question, can Malaysia’s first-past-the-post system uphold electoral justice?

According to political philosopher John Rawls, the term “justice” is fairness, where a society of free citizens enjoy equal fundamental rights and relate to each other as equals within a social order defined by reciprocity.

In other words, a basic social structure is distributively just if there is a balance between the conflicting interests of citizens on it.

The reality is that there is no perfect electoral justice. A voter in the Damansara constituency may never be the same as a voter in the Putrajaya constituency.

However, Rawls viewed justice from an institutional point of view, and not merely from an individual point of view.

Section 2 of the Thirteenth Schedule of the Federal Constitution stipulates that the number of electors within each constituency in a state should be “approximately equal”, although rural constituencies can be exempted from this requirement due to the “difficulty of reaching electors”.

Therefore, to preserve electoral justice, malapportionment can be allowed as long as the strict principles outlined in the Federal Constitution are obeyed. Nevertheless, gerrymandering, merely for the sake of favouring a certain political party or coalition, must be prevented at all costs.

The writer still believes that first-past-the-post system is the most suitable voting system for Malaysia, at least for now. Compared to other voting systems, one of the biggest advantages of the first-past-the-post system is that voters get to clearly understand who are they voting for.

If they decide to get rid of their representative, they can easily do so by voting for another candidate in the next election.

In essence, political leaders come and go but the pursuit for electoral justice in Malaysia must never stop.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of Malaysiakini.

RM12.50 / month

- Unlimited access to award-winning journalism

- Comment and share your opinions on all our articles

- Gift interesting stories to your friends

- Tax deductable