LETTER | Don't hide behind parliamentary immunity

LETTER | Expectedly, parliamentary immunity has been raised against the MACC intervening with regard to statements or speeches made by MPs in the Dewan Rakyat.

“MACC must understand that MPs have parliamentary immunity.

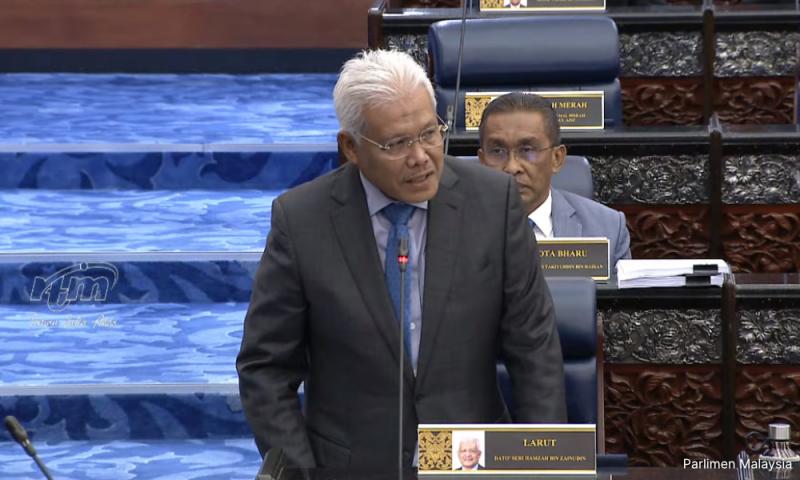

“An MP has the right to determine when he or she wants to file a report,” said Bersatu secretary-general and opposition leader Hamzah Zainudin.

Parliamentary immunity for MPs is provided for in Article 63(2) and (3) of the Federal Constitution which read as follows:

(2) No person shall be liable to any proceedings in any court in respect of anything said or any vote given by him when taking part in any proceedings of either House of Parliament or any committee thereof.

(3) No person shall be liable to any proceedings in any court in respect of anything published by or under the authority of either House of Parliament. For members of state legislative assemblies, the immunity can be found in Article 72(2) and (3), which are similarly worded.

In India, the immunity is in Article 105(2) and Article 194(2) of its Constitution which state that no MP/state assemblyperson shall be liable to any proceedings in any court in respect of anything said or any vote given by him in Parliament/legislature or any committee thereof, and no person shall be so liable in respect of the publication by or under the authority of a House of any report, paper, votes or proceedings.

It can be seen that constitutional provisions in the Federal Constitution and the Indian Constitution are in pari materia, which literally means relating to the same matter.

So, when an Indian court - more so the apex court - interprets the constitutional provisions, it is persuasive.

Just last week on March 4, in a landmark decision, a seven-judge Constitution Bench of the Supreme Court of India unanimously ruled that MPs and Members of Legislative Assemblies could not claim any immunity from prosecution for accepting bribes to cast a vote or make a speech in the House in a particular fashion.

The Indian apex court said that privileges and immunities “are not gateways to claim exemptions from the general law of the land”. Bribery is not protected by parliamentary privilege, it said in no uncertain terms.

Chief Justice of India D Y Chandrachud, who delivered the judgment of the court, said: “Corruption and bribery of members of the legislature erode the foundation of Indian parliamentary democracy. It is destructive of the aspirational and deliberative ideals of the Constitution and creates a polity which deprives citizens of a responsible, responsive, and representative democracy.”

In so ruling, the chief justice said that the court disagreed with and overruled a 25-year-old majority view of the court, laid down in the infamous JMM bribery case judgment of 1998, that lawmakers who took bribes were immune from prosecution for corruption if they go ahead and vote or speak in the House as agreed.

According to the chief justice, the majority on the five-judge bench in the JMM bribery case had erred - a grave error that the court did not want to perpetuate.

The head of Indian judiciary considered representative democracy was at stake and dismissed notions that whittling down of parliamentary immunity would expose a vote or a speech made by opposition lawmakers in the House to criminal investigation and thus enhance the possibility of abuse of the law by political parties in power.

Bribery is destructive to the “aspirational and deliberative ideals of the Constitution and creates a polity which deprives citizens of a responsible, responsive and representative democracy”.

While parliamentary immunity seeks to sustain an environment in which debate and deliberation can take place within the legislature, it would kick in only if a legislator acts in furtherance of “fertilising a deliberate, critical and responsive democracy”.

Inspired by the unanimous decision of the Indian Supreme Court, one may argue that constitutional parliamentary immunity in Malaysia should not shield a member of the legislature, be it Parliament or the state legislature, from liability in respect of bribery or anything said in respect of allegation of bribery when taking part in any proceedings in the House of a legislature.

Bribery erodes the foundation of parliamentary democracy. Its commission and allegations of it, even in the House of a legislature, should be dealt with by the general law of the land.

The decision of the Indian Supreme Court is not binding in Malaysia. However, one would have thought that Hamzah would stand on a higher moral ground to call for his fellow opposition members to report allegations of bribery as mandated by “the general law of the land” rather than hide behind parliamentary immunity.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of Malaysiakini.

RM12.50 / month

- Unlimited access to award-winning journalism

- Comment and share your opinions on all our articles

- Gift interesting stories to your friends

- Tax deductable