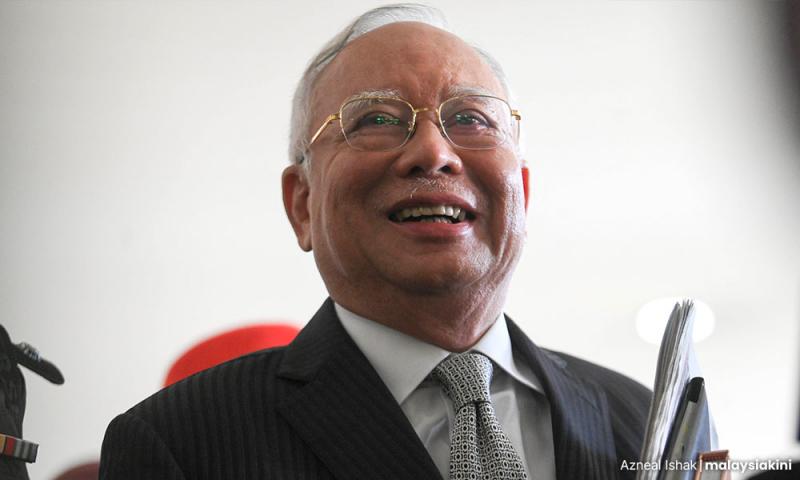

LETTER | Najib's SRC review: Majority decision binds

LETTER | Umno supreme council member Mohd Puad Zarkashi yesterday challenged the Malaysian Bar to respond to Chief Judge of Sabah and Sarawak Abdul Rahman Sebli’s dissenting judgment.

He said Najib should have been acquitted after being denied a fair trial.

Allow me to respond.

It must be said at the outset that it is the majority decision that is binding. But a dissenting voice may one day be said to be correct.

Take the example of Lord Atkin’s dissenting judgment in the English case of Liversidge v Anderson and Another (1941) before the House of Lords, then the apex court.

The case concerned the relationship between the courts and the state, and in particular the assistance that the judiciary should give to the executive in times of national emergency. It concerned the legality of the detention of one Robert Liversidge by Sir John Anderson, the then Secretary of State for Home Affairs (home minister) under the Defence (General) Regulations 1939.

The regulations allowed the home minister to detain someone if he had “reasonable cause to believe”, among other grounds, that the person was a threat to national security.

The majority of the law lords gave the regulations a subjective interpretation in that they deferred to the discretion of the home minister. The burden of proof was therefore on the detainee to show that his detention was unlawful. The majority saw it fit to allow the home minister to exercise such broad powers.

‘Reasonable cause’

Lord Atkin, however, vigorously disagreed. His Lordship noted that the regulations originally required that the home minister “be satisfied” that there were reasons to detain the suspect. Parliament changed those words to “reasonable cause to believe”, rendering the detention to be made on objective grounds.

Lord Atkin was therefore of the view that the burden to justify the detention was on the home minister. In a strongly worded judgment, His Lordship said:

“I view with apprehension the attitude of judges who, on a mere question of construction, when face to face with claims involving the liberty of the subject, show themselves more executive-minded than the executive. Their function is to give words their natural meaning…

“In a case in which the liberty of the subject is concerned, we cannot go beyond the natural construction of the Statute.

“In this country amid the clash of arms the laws are not silent. They may be changed, but they speak the same language in war as in peace. It has always been one of the pillars of freedom, one of the principles of liberty for which on recent authority we are now fighting, that the judges are no respecters of persons and stand between the subject and any attempted encroachments on his liberty by the executive, alert to see that any coercive action is justified in law.

“In this case… I protest, even if I do it alone, against a strained construction put upon words with the effect of giving an uncontrolled power of imprisonment to the Minister.”

Almost 40 years later in 1980, in the case IRC v Rossminster & Others, again before the apex court, Lord Diplock, in considering the power of tax revenue officers in conducting raids, was of the view that it was up to the raiding officers to justify that they had reasonable grounds to raid.

When the majority is wrong

Referring to Lord Atkin’s dissent in the Liversidge case, Lord Diplock said:

“For my part I think the time has come to acknowledge openly that the majority of this House in Liversidge v Anderson were expediently and, at that time, perhaps, excusably, wrong and the dissenting speech of Lord Atkin was right.”

Thirty years later in 2010 in the case of Her Majesty’s Treasury & Others v Mohammed AlGhabra, the question before the apex court - now called the Supreme Court - was the legality of certain anti-terrorism legislation. Lord Hope opined as follows:

“The case brings us face to face with the kind of issue that led to Lord Atkin’s famously powerful protest in Liversidge v Anderson... Lord Bingham of Cornhill, having traced the history of that judgment, said that we are entitled to be proud that even in that extreme national emergency here was one voice - eloquent and courageous - which asserted older, nobler, more enduring values: the right of the individual against the state; the duty to govern in accordance with law; the role of the courts as guarantor of legality and individual right; the priceless gift, subject only to constraints by law established, of individual freedom.”

Like Lord Atkin’s dissent, Rahman’s dissent may one day be said to be correct. It may take years, like the years it took to acknowledge the correctness of Lord Atkin’s dissenting speech.

But for now, the majority decision in Najib’s application for review of the Federal Court decision binds.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of Malaysiakini.

RM12.50 / month

- Unlimited access to award-winning journalism

- Comment and share your opinions on all our articles

- Gift interesting stories to your friends

- Tax deductable