LETTER | Why culturally responsive education benefits Orang Asli students

LETTER | The Malaysia Education Blueprint 2013-2025 has achieved remarkable milestones in Malaysia’s education system with the increase in national enrolment percentages at the primary and secondary levels.

In particular, the ministry initiated the Zero Student Dropout programme which resulted in a further decrease in the national dropout rate from 1.13 percent in 2020 to 1.11 percent, and 0.99 percent in 2021 and 2022, respectively.

While the achievement itself is commendable, the narrative of progress belies a stark reality for Orang Asli students who continue to be left behind.

Orang Asli students face persistent challenges in accessing an inclusive educational environment, with the difficulties exacerbated by the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic.

While the dropout rates from primary to secondary school stood at 3.2 percent nationally in 2018, the figure for the Orang Asli demographic stood at 23.3 percent.

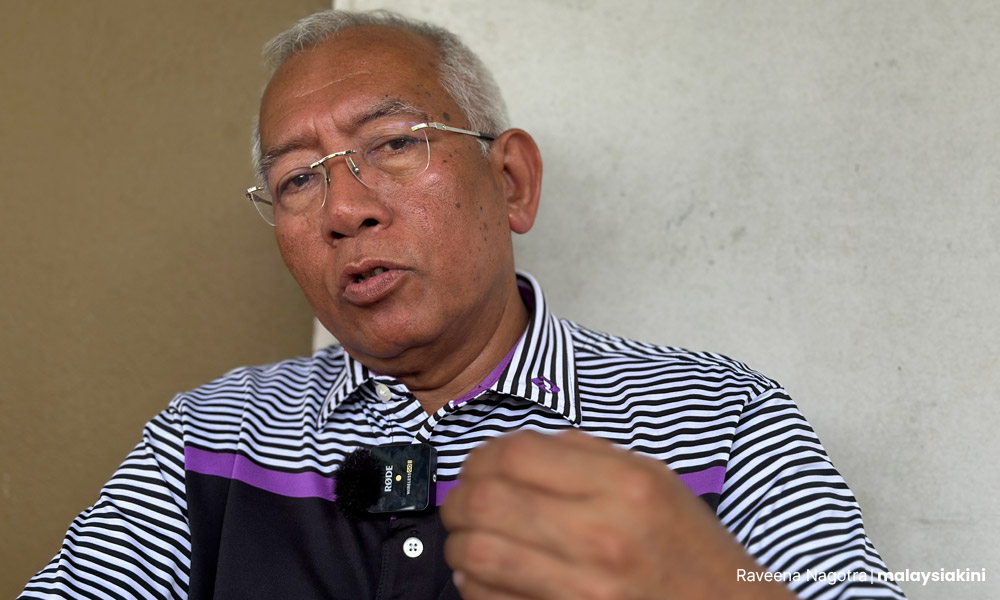

Recently, Mahdzir Khalid, the former rural development minister mentioned at the Orang Asli Consultative Council (Mapoa) that there was an improvement with school dropout rates now standing at approximately over 10 percent for Orang Asli children.

Recognising this education disparity, both government and NGOs have implemented various policies and programmes aimed at addressing the challenges.

However, translating education policy recommendations into tangible outcomes on the ground remains a daunting task.

Often, there is a gap between policy intent and implementation, resulting in unfulfilled objectives and unrealised impact. Policy-making and implementation are shaped by certain perspectives and positions, which in turn impact educational practices and processes.

Orang Asli communities should be centred as their own agents of change and given a multi-stakeholder platform to participate in the process of formulating Orang Asli-related policies.

A key aspect of policy-making and programme implementation towards the Orang Asli community has been shaped by deficit discourse.

While Orang Asli schools do have lower attendance rates below the national average, we should broaden our focus to wider issues of marginalisation and disenfranchisement that Orang Asli students have to grapple with.

This deficit discourse lays the responsibility on Orang Asli students and parents for not coming to school and measures definitions of learning by solely focusing on conventional measures of school assessments and academic achievement.

Such discourse is sometimes internalised and causes the community to question their learning abilities when in reality, it is their needs that are not being met.

Alternatively, the focus should be on empowering their capabilities in a way that celebrates their indigenous knowledge and provides access to opportunities to reach their full potential.

The Orang Asli people, indigenous to Peninsula Malaysia, are diverse communities comprising at least 18 sub-ethnic groups with their own respective ethnic languages and cultural identities.

Thus, a one-size-fits-all approach simply won’t suffice. Education interventions to improve access to education must be catered to the specific needs of the Orang Asli community and their context.

Education programmes targeting Orang Asli students can be typically divided into two kinds of objectives.

The first primarily focuses on enhancing academic achievement and school attendance among Orang Asli students with an emphasis on reading, writing and arithmetic skills (3M).

Programmes ranged from capacity training of teachers and students, improving the quality of teaching and learning while maximising student potential, and advocating for an education pathway for Orang Asli students to gain market-relevant skills.

Preserving their knowledge

The second type focuses on empowering the community to preserve their Orang Asli values, language, culture and way of life from endangerment.

These programmes recognise that the Orang Asli communities possess indigenous knowledge that is under threat. Programmes range from community mapping to documentation of traditional languages, crafts and folklore.

Both kinds of programmes cater to a specific need but the critical consideration is whether these programmes align with the aspirations of the Orang Asli students as well as the broader parent and teacher community.

Therefore, designing educational initiatives aimed at Orang Asli students should create space for communities to determine their educational settings, rather than imposing externally conceived solutions.

Recognising the unique strengths, talents, aspirations and challenges of marginalised communities, it is imperative to prioritise their input and tailor programmes in a way that addresses their areas of concern instead of our own programme indicators for success.

Even while managing funding constraints, platforms for dialogue, collaboration and knowledge-sharing with Orang Asli communities should be built into the programme design, while adopting best practices for community engagement, checking our own biases as non-Orang Asli project designers and ensuring consent is respected.

Importantly, in the event of programme shortcomings, accountability should not fall on the recipients of the programme, but rather prompt reflection and improvement within the programme’s framework.

Accountability

Thus, there is a need to depart from the deficit paradigm when framing Orang Asli education programming.

Instead of attributing fault to the community, the focus of both education policy and programming should look to also address larger structural inequalities and contribute to best practices that mitigate our biases and better cater to the needs of the Orang Asli students.

Accountability measures for programmes should also be in place with community-contextualised targets within the education landscape.

We need to reframe the trajectory of education intervention programming in alignment with the aspirations of diverse Orang Asli communities.

If genuine inclusive empowerment is our aim, we must prioritise platforms for communities to determine their educational environments as they possess the most intimate understanding of their circumstances.

Writer is a researcher in the social policy unit at the Institute of Democracy and Economic Affairs (Ideas). Her views here are from the perspective of a non-Orang Asli.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of Malaysiakini.

RM12.50 / month

- Unlimited access to award-winning journalism

- Comment and share your opinions on all our articles

- Gift interesting stories to your friends

- Tax deductable