Finding the political will to help stateless children

FEATURE | Efforts to solve the issue of stateless children in Malaysia have encountered numerous difficulties, not least among them the lack of “political will” of leaders and politicians.

The phrase “political will” is defined as “the intention or assurance of government in the action of executing policies, particularly policies that are not preferable or effective”.

Previously in the first part of this series, Malaysian NGO Voice of the Children president Sharmila Sekaran pointed out that political will is an important factor in resolving the issue of stateless children in Malaysia.

However, when asked about the issue of stateless people in 2015, Home Minister Ahmad Zahid Hamidi replied, “Based on the definition of ‘stateless’ (which) refers to a person who has no nationality or citizenship in any country in the world, there (are) no stateless people in Malaysia because they are not allowed to enter this country without legal travel documents.”

Malaysia did not recognise the existence of stateless people that year.

Nevertheless, a year later, Zahid suddenly admitted that there were almost 300,000 stateless children aged between one and 18 who were born in Malaysia, but were not given Malaysian citizenship.

The inconsistent statements made by the Home Minister are a prime example of the careless attitude the Malaysian government has towards this issue. The difficulties faced by stateless people are seemingly only addressed when it suits politicians, with perfunctory measures taken otherwise to temporarily placate the masses.

Who should be held accountable?

A late registration fee is incurred when a child is registered at the National Registration Department (JPN) more than 42 days after his or her birth. Late registration fees include a “birth register search” costing RM5, a processing fee of RM10 and a penalty that is not to exceed RM50.

According to a 2013 status report on children’s rights published by the Child Rights Coalition Malaysia, the fee was abolished in 2013.

The measure to abolish the late registration fee was supposed to “help the poor and marginalised groups who are unable to register the birth of their child due to cost, the remote areas where they live, or awareness of the importance of this document much later after the birth of the child,” according to the report.

However, the charge is still currently listed on the JPN website.

A search among official announcements and news reports found no mention of the abolishment of the late registration fee. Calls to relevant non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and governmental units were made, but no replies had been received at the time of publication.

Was the abolishment of the late registration fee just a rumour, or was its implementation postponed to some unknown later date?

Previous claims that children without proof of citizenship could receive an education have also led nowhere.

In March 2009, Alimuddin Mohd Dom, the director-general of education in the Education Ministry at the time, released a written announcement which stated, “Even children without identification documents are entitled to an education and should be admitted to government schools, as long as one parent is a Malaysian citizen, or a written testament which states the child is a Malaysian citizen is submitted by a village leader.” The rule was to be applicable to all states in Malaysia.

This information has just begun to circulate among the public in 2017. Children who would have had the chance to receive an education remain excluded from the national system.

How is it that none of the state-level education departments and relevant NGOs received notice from the Education Ministry during this eight-year gap?

As of now, only Kedah has begun implementing the measure.

“With good training and education, (children) can imagine themselves enrolling in university in the future, becoming whoever they want to be.

"However, stateless children can't imagine themselves doing anything; they too, wish to be doctors or teachers, but they know it will be tough, (since) they cannot attend classes or sit for examinations in school,” Sharmila laments.

‘Our family has a guardian angel’

Unlike other stateless children in Malaysia, A-Qing and her siblings were lucky to have the opportunity to go to school.

A-Qing’s father reveals that he received some help from a “high-ranking official” during the application process, a contact from years of work. A letter from the officer allowed A-Qing and her siblings to receive the free education and medical benefits granted to Malaysian citizens, even before receiving their birth certificates.

Hence, their lives were not completely affected by their statelessness, and they could even sit for their driving tests and receive driving licences. (Editor’s note: For the circumstances leading to A-Qing’s statelessness, please read Part 1 of the series here).

The “protection” afforded by their links to the officer has its limits, however.

If she wishes to further her studies, A-Qing has to apply for university as an Indonesian citizen. She will have to pay more fees for an international student visa, along with higher tuition and resource fees.

The financial burden incurred by just one of the siblings going to university has led A-Qing to postpone her studies, at least until she receives Malaysian citizenship.

Meanwhile, A-Qing and her two younger brothers are attempting to apply for citizenship under Article 15(a) of the Federal Constitution, which allows any individual below the age of 21 to apply for citizenship under special circumstances.

Their applications are still being processed. Once authorised, the siblings will become Malaysian citizens. However, it is uncertain how long the application process will take.

Other parents in similar situations have reached out to A-Qing’s father for help, but this has brought more stress to the family.

"There are many others like us in Malaysia, but how can we offer to help? We are already under a lot of stress to prepare funds for our children’s studies.

"We can be heroes, but we have no courage without money," A-Qing’s father says with a touch of emotion in his voice.

Malaysia's international obligations

The Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) is a legally-binding international convention which is applicable to those under the age of 18.

It established a standard for the treatment of children by declaring that children are entitled to their own rights, independent of countries or parents. The CRC serves as a protective framework for children along with the Federal Constitution, as mentioned in Part I of this series.

Although Malaysia ratified the CRC in 1995, the implementation of this convention has been complicated by the dual legal system in Malaysia, because the two legal systems define a child differently.

Malaysia observes both Syariah Law and Civil Law. Syariah Law defines males below the age of 18 and females under the age of 16 as children, while Civil Law defines anyone under the age of 18 as a child regardless of gender. This has resulted in different standards for obligations to be fulfilled by the Malaysian government.

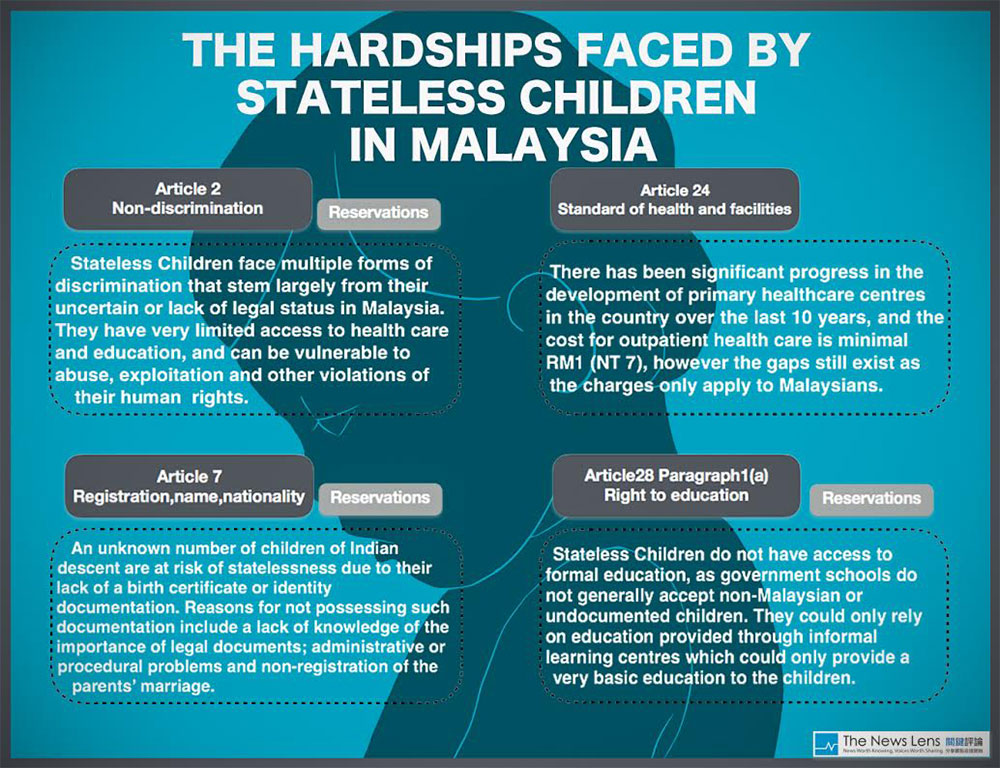

In addition to that, the government of Malaysia still has reservations regarding five core articles in the CRC which ensure the minimal rights and dignity of children. These articles are as follows:

- Article 2 (Non-discrimination)

- Article 7 (Registration, name, nationality, care)

- Article 14 (Freedom of thought, conscience and religion)

- Article 28, paragraph 1(a) (Right to education)

- Article 37 (Detention and punishment)

Even the implementation of articles considered acceptable by the Malaysian government deviates from CRC practices (chart).

Therefore, even under the CRC, children at risk of becoming stateless and stateless children in Malaysia are not afforded the appropriate protection.

What protection that the Federal Constitution and the CRC combined could have provided for stateless children has been limited by the government’s inaction and a narrow interpretation of the law.

Sharmila, the NGO president, says this is purely a legal and administrative problem.

“Take the most basic case of the administrative procedures of birth registration.

“Assume [the authorities] know that this child comes from Cambodia. Even if he or she is stateless, [Malaysia] can help to register the birth of that child because of the wide coverage of the JPN. The documentation could then be delivered to [the Embassy of Cambodia],” said Sharmila.

This measure could provide a solution towards resolving the issue of statelessness, Sharmila says, but it all hinges on “political will”.

These two words sum up her experience since founding Voice of The Children in 2009 with a group of lawyers. Although the situation in Malaysia has seen some improvement, the organisation believes the government could be doing much more. At the very least, they must first admit to the existence of stateless people in the country.

The ‘lucky’ ones

It was the Lantern Festival when we talked to A-Qing. The joyful crackling of firecrackers contrasted with the desolation of statelessness, but A-Qing’s optimism and occasional self-deprecating humour helped to lighten the mood.

As luck would have it, the JPN turned a blind eye when A-Qing’s younger sister was registered at birth, and she is the only child in the family that holds Malaysian citizenship.

“This is ‘Malaysia Boleh’! If (JPN) had made an effort to check, my younger sister would be in the same boat (as us other siblings)!” A-Qing answered with a smile. She looked over at her younger sister, who was checking Facebook at her desk.

The oversights of the Malaysian government and petty corruption have helped A-Qing and her siblings, but other stateless children have not been as fortunate.

They are currently bearing the consequences of such negligence, excluded from the education, healthcare, and legal systems. They cannot leave Malaysia, but they cannot assimilate into society either.

The refusal of Malaysia’s government and its society to acknowledge the existence of stateless people is costing them the chance to improve their lives.

Even as A-Qing hides her anxiety behind her bright laughter, one can still feel the uncertainty she carries of the long wait ahead of her, of the possibility that it may all have been for nothing.

“What else can I do but be patient?”

This article was first published in Mandarin in The News Lens here. Malaysiakini has been authorised to publish the English version, which was translated by Ziqing Low, Chee-An Ng and Hui-Yee Chiew.

Part 1: 'An invisible jail' - stateless children in Malaysia

Part 2: Finding the political will to help stateless children

RM12.50 / month

- Unlimited access to award-winning journalism

- Comment and share your opinions on all our articles

- Gift interesting stories to your friends

- Tax deductable