Sabah and Sarawak downgraded by their MPs in 1976

COMMENT | For the first time, not just since Pakatan Harapan came into power, but since the loss of the then-government’s two-thirds parliamentary majority in 2008, our Parliament will vote on a constitutional amendment.

The amendment tabled is very straightforward, without any legal-constitutional jargon, and is at the very beginning of our Federal Constitution. It is a simple provision, but a big question: when we call ourselves Malaysia, who are we?

Since an amendment that came in force on August 27, 1976, Article 1(2) says: “The States of the Federation shall be Johore, Kedah, Kelantan, Malacca, Negeri Sembilan, Pahang, Penang, Perak, Perlis, Sabah, Sarawak, Selangor and Terengganu.”

When Malaysia was formed on Sept 16, 1963, it read: “the States of the Federation shall be – (a) the States of Malaya, namely, Johore, Kedah, Kelantan, Malacca, Negeri Sembilan, Pahang, Penang, Perak, Perlis, Selangor and Trengganu; and (b) the Borneo States, namely, Sabah and Sarawak; and (c) the State of Singapore.”

After Singapore’s departure on August 9, 1965, the last phrase “the state of Singapore” was dropped.

The amendment now put forward by the Harapan government is to revert back to the 1965-1976 version, minus the mentions of Malaya and Borneo. If passed on April 9 (Tuesday), Article 1(2) shall read: “The States of the Federation shall be – (a) Johore, Kedah, Kelantan, Malacca, Negeri Sembilan, Pahang, Penang, Perak, Perlis, Selangor and Trengganu; and (b) Sabah and Sarawak.”

What's the big deal?

Why is the arrangement of states so important? Because it determines if Sabah and Sarawak should be treated as equal to Malaya as a whole, or just equal to its 11 states.

In other words, are Sabah and Sarawak each one of three regions in Malaysia, or 1 of 13 states?

If this is not still clear, let’s hear from three parliamentarians – incidentally, all from Malaya – in the 1976 Dewan Rakyat why they enthusiastically supported the 1/13 version, which downgraded the two states.

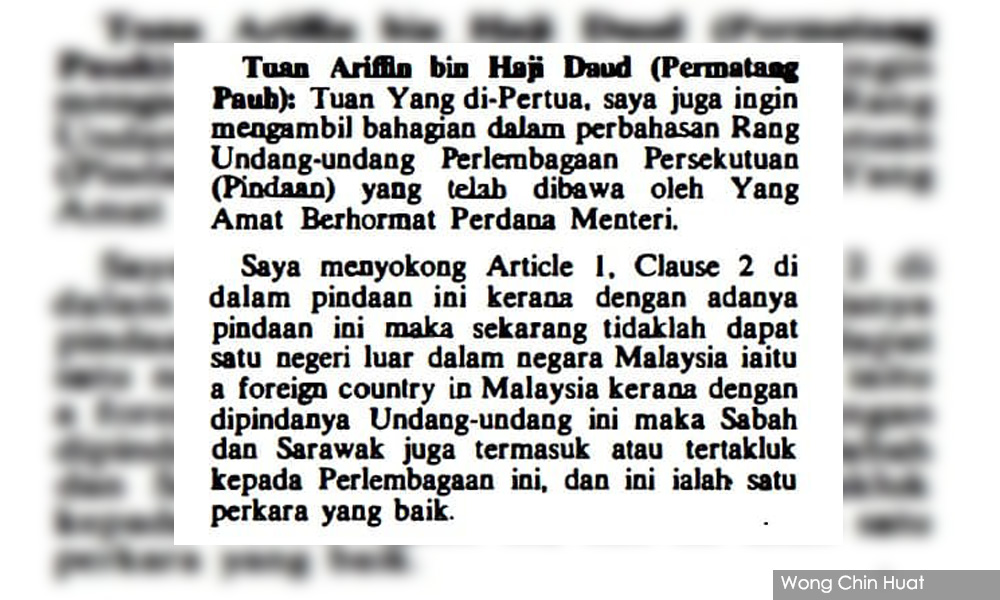

For then-Permatang Pauh MP Arifin Haji Daud, keeping Sabah and Sarawak separate from the Malayan states created the sense there was "a foreign country in Malaysia."

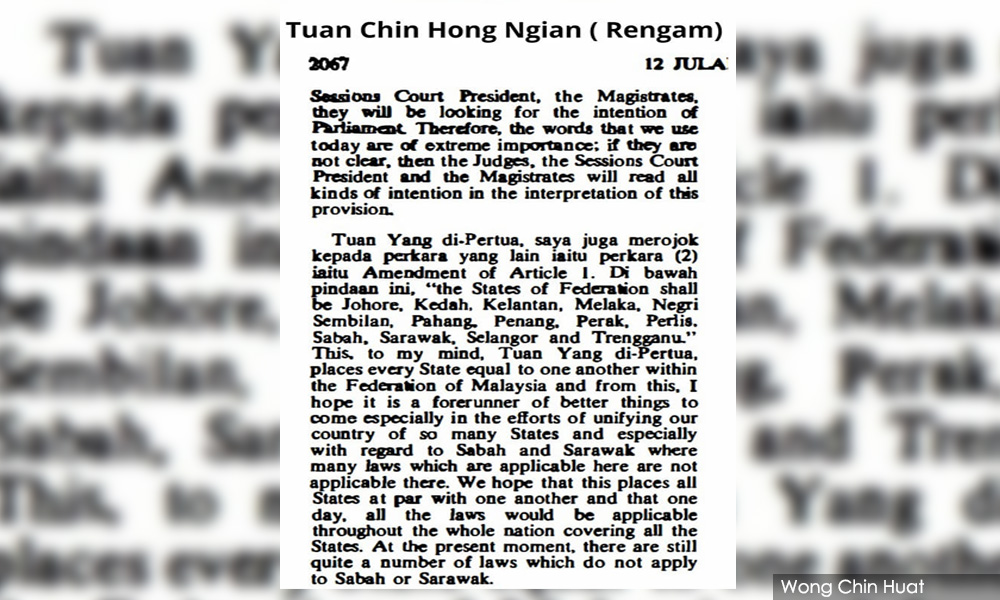

For then-Rengam MP Chin Hon Ngian, the amendment “places every state equal to one another within the Federation of Malaysia.” Further, he hoped that “all the laws would be applicable throughout the whole nation covering all the States.”

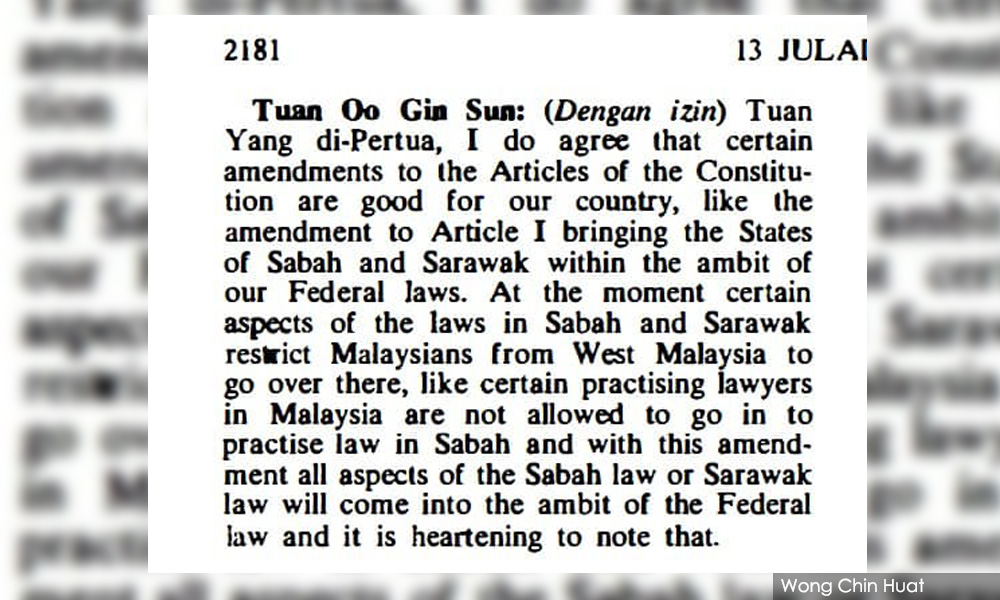

The desire for total uniformity in law was echoed by another MCA lawmaker, then-Alor Setar MP Oo Gin Sun, who saw the amendment as “bringing the States of Sabah and Sarawak within the ambit of our Federal laws.”

A lawyer himself, Oo was not happy that “lawyers in Malaysia are not allowed to go in to practice law in Sabah."

While Article 1(2) does not directly affect the division of legislative power between the federal government and the Borneo states (Ninth Schedule), the fiscal arrangements (Articles 112A-112E) and additional safeguards for the two states (Articles 161-161H), it is symbolically powerful.

It is meant to make Sabah and Sarawak “not like a foreign country,” so that all states would be equal from Perlis to Sabah. And if that idea is planted deep in enough people’s minds, especially those in Sabah and Sarawak, then laws can be uniform, too, from Perlis to Sabah.

Who voted to downgrade Sabah and Sarawak?

It is not surprising the MPs from Malaya could not appreciate diversity and decentralisation. But was this imposed on Sabah and Sarawak because they were outnumbered?

Borneo nationalists claim having one-third parliamentary seats is vital to protect Sabah and Sarawak from being bullied. Was this a case in point?

The Dewan Rakyat then had 154 members, with 24 from Sarawak and 16 from Sabah. To defeat the constitutional amendment bill, it would take only 52 votes, or 12 more on top of all Borneo parliamentarians.

Did the bill pass through because Sabah and Sarawak parliamentarians could not get 12 extra votes?

No, the constitutional amendment bill was passed by a landslide of 130:9 for the second reading at about 7:40pm on July 13, 1976, and by another of 130:4 for the third reading an hour later.

Unwavering in voting for the damning amendment to downgrade their own states in Malaysia were 22 out of 24 Sarawak parliamentarians and 11 out of 16 Sabah parliamentarians.

So, were the remaining seven MPs from Sabah and Sarawak the saving grace? Sadly not. The seven were simply absent from the session. The nine who voted against the bill were all opposition members from Malaya.

How to get turkeys voting for Xmas?

So, how did the BN national leadership get the turkeys voting for the Christmas? The Hansard suggested that the then-prime minister Hussein Onn – or whoever advising him – to be a great tactician.

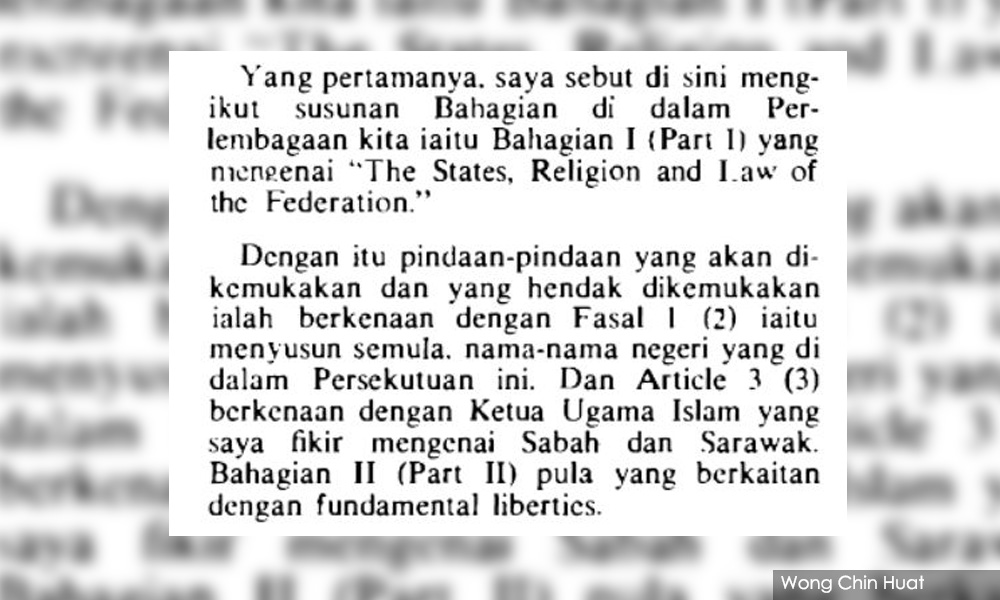

First, he disarmed the parliamentarians by characterising the amendment to Article 1(2) as innocently “rearranging the names of the Federation.”

Secondly, this amendment was put in a big package. The entire amendment (Act 354) affected 45 Articles (including three repeals and one addition) and two Schedules. The hot topics included religion, liberties, citizenship and judiciary.

Then, the Federal Constitution had 201 Articles and 13 Schedules. So, this was possibly one of the most extensive amendment packages.

Thirdly, he gave the MPs very limited time to deliberate. With the first reading on July 5, the second reading started a week later and lasted for a total of seven and a half hours over two days.

Excluding the prime minister who tabled the bill and concluded the debate, a total of 26 MPs participated, but from the fourth speaker onwards, most got to speak only for 10-15 minutes. Unsurprisingly, most spoke on the hot topics and overlooked the “innocent” Article 1(2).

Nevertheless, one cannot help but be surprised that the statements by MPs of Permatang Pauh, Rengam and Alor Setar failed to wake up those from Borneo. No one was offended by the view that respecting the special status of Sabah and Sarawak is akin to having a foreign country in Malaysia.

Not a single parliamentarian from Sabah bothered to join in the debate. Three from Sarawak did – chief minister Abdul Rahman Ya’kub (Payang), Stephen Yong (Bandar Kuching) and Latip Haji Dris (Mukah).

The chief minister justified the amendment to Article 1(2) by dismissing the word “Borneo”, which included the Indonesian provinces. Interestingly, he also expressed his desire to see a unified judiciary with no division between the courts in Malaya and Borneo.

While not touching on Article 1(2), Latip from PBB also dismissed the use of “Borneo,” seeing the colonial connotation, while Yong from SUPP spoke on personal liberty and citizenship.

Was Article 1(2) amended just to do away the word 'Borneo'? Or, was it for a more uniform and ‘integrated’ Malaysia desired by some Sabah and Sarawak people, PBB for example?

If downgrading to be just another state was what the majority of Sabah and Sarawak people then wanted, could we fault the amendment?

Will Sabah and Sarawak vote to keep the 1976 deal?

Now, Sabah, Sarawak and Labuan have between them 57 votes in the Federal Parliament.

Harapan and its allies in Warisan and UPKO have 137 MPs, including 12 from Sarawak and 19 from Sabah.

Regardless how West Malaysian parliamentarians vote on that, the 25 opposition MPs – 18 from GPS, two ex-Umno independents and one each from PBS, Star, Upko, Umno Sabah and Parti Sarawak Bersatu (PSB) – will decide if the undoing of the 1976 amendment can happen.

A comprehensive deal to make Malaysia a more equal tripartite union between Malaya, Sabah and Sarawak may take at least one or two years of negotiation. More than a parliamentary select committee as some propose, but perhaps also a royal commission of inquiry or another inter-governmental committee.

Undoing Hussein’s 1976 masterstroke would be a low-lying fruit that symbolically restores Sabah’s and Sarawak’s dignity, and put the two states in a stronger position for further negotiation.

But is this what Sabah and Sarawak want? Will Sabah and Sarawak parliamentarians today vote differently from their predecessors 43 years ago?

Interested readers can download the Hansard. Those who are keen to see the undoing of the 1976 version can click here.

WONG CHIN HUAT is a political scientist with the multi-disciplinary Jeffery Sachs Centre on Sustainable Development, Sunway University. His research focuses on political institutions and group conflicts.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of Malaysiakini.

RM12.50 / month

- Unlimited access to award-winning journalism

- Comment and share your opinions on all our articles

- Gift interesting stories to your friends

- Tax deductable

Wong Chin Huat

Wong Chin Huat