Orang Asli voices may go silent as languages face extinction

Editor’s note: This article contains audio clips of the Orang Asli languages. Click on the clips to hear them.

SPECIAL REPORT | The rushing of a river, buzzing of insects and chirping of birds are all parts of a jungle chorus that urbanites are scarcely familiar with. Yet for centuries they have been part of the symphony that colours Malaysia’s once-dense interior. Woven into the harmonious tapestry of sounds are the languages of the forest’s most ancient dwellers.

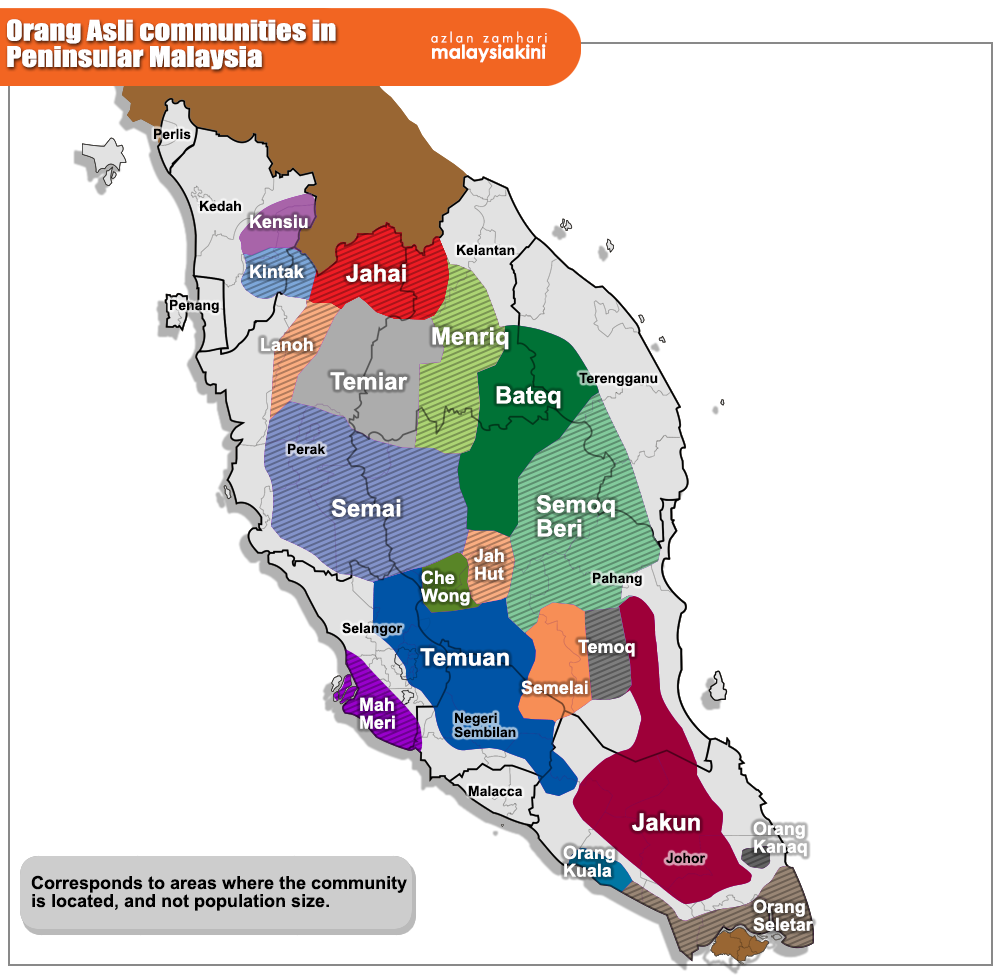

The 18 groups that make up the broader Orang Asli community have lived here for an estimated 4,000-5,000 years. Now numbering about 215,000, they live across Peninsular Malaysia, from the remote jungles of Kelantan to islands off Klang.

There is a tendency to portray the Orang Asli as homogenous, but they are nothing of the kind.

As communities can be nomadic, live in remote areas and are at times reclusive, official population figures sometimes vary widely between official data and those by NGOs.

But it is generally accepted that the Orang Asli are divided into three main groups - the Negrito, Proto-Malay and Senoi. Each of these is further divided into six groups.

The disparity of size among the groups is wide. The largest of the group, the Semai, number more than 50,000.

Groups like the Bateq, Jahai, Semoq Beri, Jah Hut, Mah Meri, Orang Seletar and Orang Kuala number less than 6,000, while the smallest of the tribes, the Kensiu, Kintak, Lanoh, Mendriq, Che Wong and Orang Kanaq, all have less than 1,000 registered people per tribe.

Vanished groups

This means their language and culture may go extinct within a generation - which has happened before.

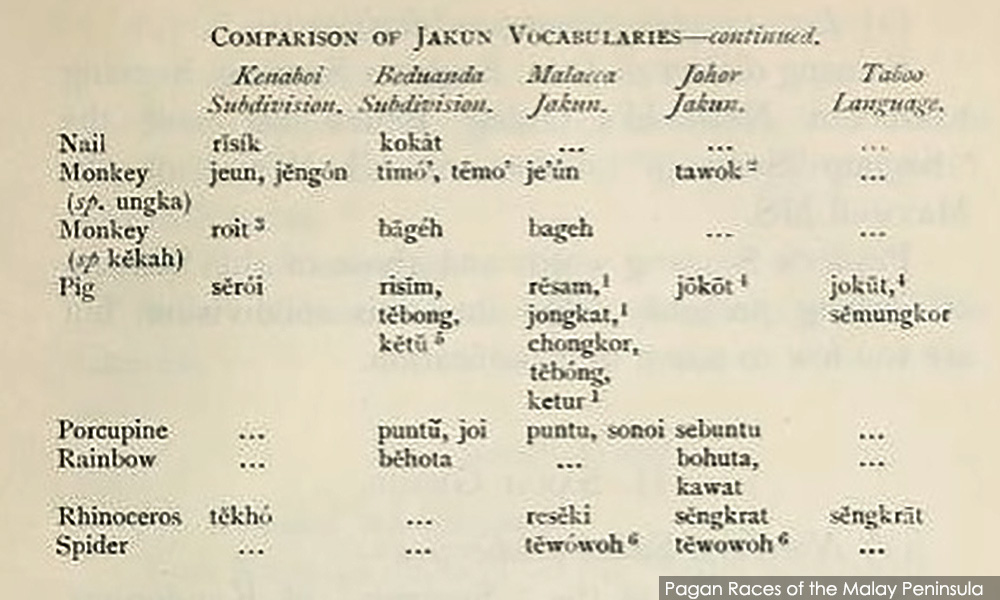

There was a tribe called the Kenaboi who spoke a unique language. They lived in the northern parts of Negri Sembilan, but their numbers dwindled as they started to integrate with the larger Temuan community. Over time the group’s language and culture became extinct.

What remains are approximately 250 words compiled in 1880 by researcher DFA Hervey and referred to in the book Pagan Races of the Malay Peninsula by WW Skeat and CO Blagden, published in 1906.

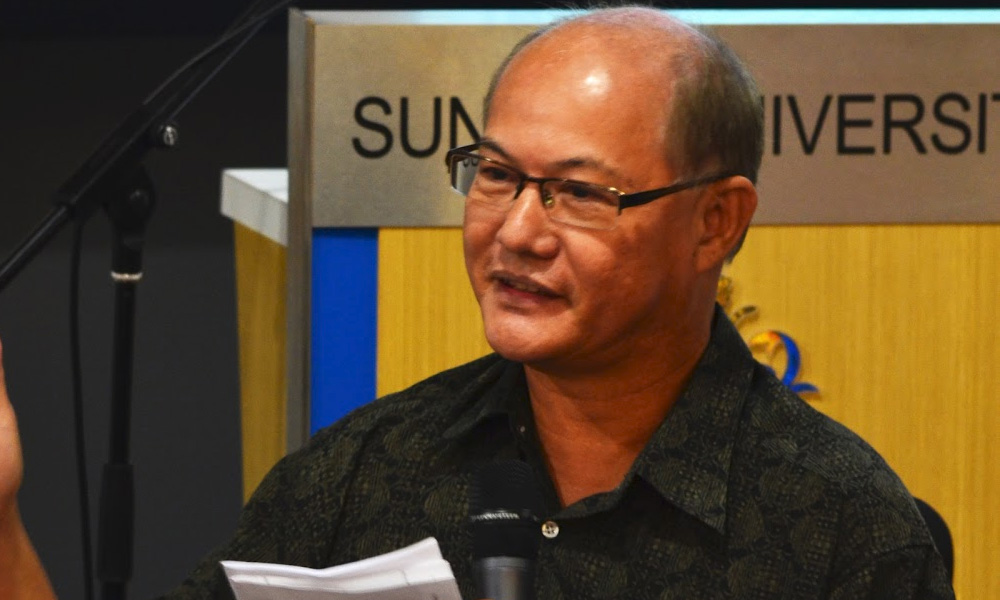

But Bah Tony, former Persatuan Orang Asli Semenanjung Malaysia president, believes the smaller communities are self-preserving to a certain degree.

“I don’t think there is an immediate danger of languages dying out as they themselves will take steps to self-preserve.”

Tony cited the example of a group of Lanoh people based around Lasah, Sungai Siput, Perak.

“At one time, to combat Communists during the Emergency, the Temiar were relocated to the Lanoh area. The Temiar are more dominant, both in terms of numbers and personality. So what happened was, after a while, the Lanoh moved to Lenggong.

“This was a strategy to make sure they didn’t disappear. Those who moved survived with their language and culture intact, while those who stayed intermarried and slowly took up Temiar ways, although they may still speak Lanoh among themselves,” he said.

Tony said communities often find it challenging to preserve their identities when forced to relocate.

“The problem comes when the government starts to relocate and regroup them, thinking of the Orang Asli as one. This is something we should not do anymore, as each land, language and culture is unique.”

Just like in Lasah, two distinct Orang Asli communities were put together by the government in Sungai Chiong, near Grik.

The Jahai and the Temiar had existed relatively close to each other, but had distinct territories and cultures.

“Again, they were brought together by the government, and you had a case where the children from one group would start to pick up the other’s language. But the Jahai definitely took steps to preserve their own independence.”

Complex language

While the Orang Asli are broken into three larger ethnic groups, the linguistic groups fall into two main categories, with some languages sounding closer to the Malay language.

Others, which are Austroasiatic (Mon-Khmer), would sound alien to most Malaysians, Tony said.

The languages also differ in grammatical form and syntax. The Temiar language, among the most widely spoken by the Orang Asli, uses passive terms to describe active situations.

The Kensiu words, meanwhile, vary according to tongue height and nasal intonation. It is also a written language with 28 vowels and a script resembling that of the Thai language, although some experts believe it is no longer in use. In 2015, the number of Kensiu native speakers numbered less than 300.

The languages are also unique to one another, in that they are heavily influenced by the surroundings.

Forest-dwelling communities have more words describing certain trees, animals or fruits, while coastal communities have a richer vocabulary for marine life, Tony said.

Among the less spoken languages is one which is likely to have the least number of speakers. Speakers of Jedek are so few they do not form a community of their own. Instead, they identify themselves as part of the Mendriq or Bateq tribes.

Keeping a language alive

With more and more Orang Asli children obtaining formal education, it is the schools that hold the key to preservation, Tony said.

Already, he said, languages like Temiar and Semai are taught in schools attended by a majority of Orang Asli students.

“But it is difficult to expand to other Orang Asli languages because there are few teachers,” he said.

Popular culture may fill the gap.

One such example is Radio Asyik, the RTM radio station that broadcasts daily from 8am-11pm. It was founded in 1959 as a 30-minute programme presented in the Temiar and Semai languages.

In 2001, Radio Asyik started producing programmes in Temuan and Jakun languages. Although still only catering to the languages most widely spoken, Tony believes Radio Asyik has played a crucial role in preserving the languages of the Orang Asli.

Other popular efforts of preservation include the work of Antares, a veteran of the Kuala Lumpur arts scene, who has lived with the Temuan in Kampung Perak in Selangor since 1992.

His works include Tanah Tujuh, a book on Temuan folklore, which was published in 2007, with a related Temuan glossary of about 300 words.

Antares also produced a documentary called Guardians of the Forest in 2000, and in 2002 produced a CD of songs by Temuan singer Minah Angong.

Reconnecting with heritage

The works of Antares have been used by young Temuans to reconnect to the culture they lost as they assimilate with mainstream society through education and employment.

“I was most touched when I received emails from young Temuans who had stumbled on my writings about their mythology online,” he said.

Among them was artist Shaq Koyok, who in 2017 received the Merdeka Award, which is conferred to high-achieving young Malaysians whose work made a lasting impact on society.

“Shaq and his friends thanked me for writing down their ancestral myths, albeit in English. They said my essays were the only source they could find that recorded some of the Temuan folklore!”

Shaq, who holds a bachelor’s degree in fine arts, is among young Orang Asli who were forced out of their communities by development and left with no choice, but to assimilate into city life.

“The pressures to maintain this linguistic diversity are great nowadays, not least because of the lack of practice among the younger generation and the relentless pressure of modernisation,” Shaq said.

Not much priority is given to help the young Orang Asli maintain their cultural heritage, he said, unlike in countries like New Zealand and Australia, where children are taught the history of the “first peoples”.

“All I ask is Orang Asli children be given the same opportunities to learn about their heritage, like any other child in Malaysia.”

As Orang Asli language and traditions are passed on orally, many Orang Asli children are deprived of this knowledge when they are plucked out of their community to attend residential schools far from home. Some leave their community as young as seven years old.

Timah Upih, a Semoq Beri from Kampung Sungai Berua, Terengganu, believes her language and traditions will live on, even though her community only numbers about 5,000 people.

Timah feels that even though that there are just over 5,000 of her people left, they will survive and thrive because children are taught to speak Semoq Beri as their first language.

She says the children also learn traditional dances, songs and weaving from a very young age.

“Parents should teach their children how to speak the language, as I taught my own children,” she said.

“It's important to pass them down. Old things are more cherished (barang makin lama, makin sayang).”

The Semoq Beri have withstood the challenges of assimilation with other tribes through relative isolation. Timah has only met someone from the Bateq tribe and has never heard of groups like the Kensiu or Lanoq.

The community also maintains its traditional way of life, relying on the forest and their crafts for livelihood.

Dictionaries and land rights

The Department of Orang Asli Development (Jakoa) acknowledges the threats to Orang Asli culture.

"There are various studies that acknowledge the extinction of language of the minority groups in the world.

"Among the efforts being undertaken is an ongoing study with Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka to study the language and produce dictionaries for the 18 languages," a Jakoa spokesperson said.

"Last year, the department conducted a Jedek language study. This year, it will focus on the Kensiu of Baling, Kedah, and the Kanaq in Kota Tinggi, Johor.

“Jakoa is fully committed to ensuring that the language and culture of all Orang Asli, particularly the minorities, are preserved,” the spokesperson added.

But Colin Nicholas, a forefront researcher and activist on Orang Asli concerns, said the question of cultural survival is far greater than publishing dictionaries.

The Semoq Beri of Terengganu may be able to maintain their way of life today, but encroachment through mass agriculture and logging in the neighbouring state of Kelantan indicate that these days are numbered.

Nicholas said each community has a geographical space which is tied to its specific history, culture, knowledge and identity.

“As long as the community is in possession and control of its customary land, its culture and its continuity as a people are assured. Only then can we expect Orang Asli languages, worldviews, traditions and indigenous systems to survive.”

PART 2: Once deemed 'wildlife', Orang Asli still face condescension

PART 3: Bullied, separated - national education failing Orang Asli children

RM12.50 / month

- Unlimited access to award-winning journalism

- Comment and share your opinions on all our articles

- Gift interesting stories to your friends

- Tax deductable

Martin Vengadesan

Martin Vengadesan