Is contempt of scandalising the court still relevant?

COMMENT | Recently, the attorney-general moved contempt proceedings against a lawyer for scandalising the Federal Court.

The alleged contempt arose as a result of certain articles written by this lawyer, which touched upon a particular decision of the apex court to expunge large portions of a dissenting judgment of a Court of Appeal judge.

Subsequently, the attorney-general also obtained leave to commence committal proceedings against a senior lawyer representing the former prime minister for comments that he made to the media regarding the criminal case his client is involved in.

The first lawyer in question has been convicted of contempt by the Federal Court, and a custodial sentence was imposed, in addition to a fine. The other case is still pending in the High Court. I do not wish to comment on either case, because there is a possibility of a review as the proceedings are still before the courts.

However, it is time that there is legislative intervention by the government to give a statutory basis to the common law powers of the courts to punish contempt.

The offence of scandalising the court is a species of criminal contempt. It is arguable whether this form of contempt is still in existence, or whether it has become obsolete. Unlike in Singapore, this form of contempt has not been given a statutory basis in Malaysia.

The preponderance of cases from Commonwealth jurisdictions, and even the United States, suggest that the contempt of scandalising the court has become obsolete and irrelevant in modern democracies, where public institutions are subject to scrutiny and comment in the exercise of freedom of speech and of the press.

The doctrine of open justice permits comment and reporting of decisions of the courts, and even the judicial process involved in specific cases, such as access to and disclosure of information in the exercise of such fundamental rights. Refer to the UK Supreme Court in Khuja (formerly PNM) vs Times Newspapers Limited and others.

The Indian Supreme Court in the case of Brahma Prakash Sharma and others vs the state of Uttar Pradesh, in dealing with the contempt of scandalising the court in the context of certain Bar resolutions, refused to restrict the right of the Bar to discuss the conduct of judges, and found there was no contempt of court.

Similarly, the Indian Supreme Court, in the cases of PN Duda (regarding an alleged contemptuous speech made by the minister to the Bar Council), Sheela Barse and Shri S Mulgaokar, took a robust view of the public right to criticise the administration of justice and judges.

In Duda's case, the apex court said: "Administration of justice and judges are open to public criticism and public scrutiny. Judges have their accountability to the society and their accountability must be judged by the conscience and oath of their office, that is to defend and uphold the Constitution and the laws without fear or favour. This the judges must do in the light given to them to determine what is right.

"In the free market place of ideas, criticism about the judicial system or judges should be welcomed as long as such criticisms do not impair or hamper the administration of justice."

In Sheela Barse's case, the apex court in very strong language said: "The concept of public accountability of the judicial system is, indeed, a matter of vital public-concern for debate and evaluation at a different plane.

"This is not to deny the broader right to criticise the systemic inadequacies in the larger public interest. It is the privileged right of the Indian citizen to believe what he considers to be true and to speak out his mind, though not, perhaps, always with the best of tastes; and speak perhaps, with greater courage then care for exactitude.

"The judiciary is not exempt from such criticism. Judicial institutions are, and should be made, of stronger stuff intended to endure and thrive even in such hardy climate."

In the case of Shri S Mulgaokar, the court said: "To criticise a judge fairly, albeit fiercely, is no crime, but a necessary right. Where freedom of expression subserves public interest in reasonable measure, public justice cannot gag it or manacle it.

"The court must avoid confusion between personal protection of a libelled judge and prevention of obstruction of public justice and the community's confidence in that great process."

No specific law for contempt

Here, although Parliament has the right by law to impose restrictions on freedom of speech, no written law as such has been passed to deal with contempt of court.

Therefore, reliance is placed on common law, as expressly preserved in Article 126 of the Federal Constitution, in order to punish contempt. But the power to punish contempt must not impede upon the exercise of the fundamental rights of freedom of speech and of the press.

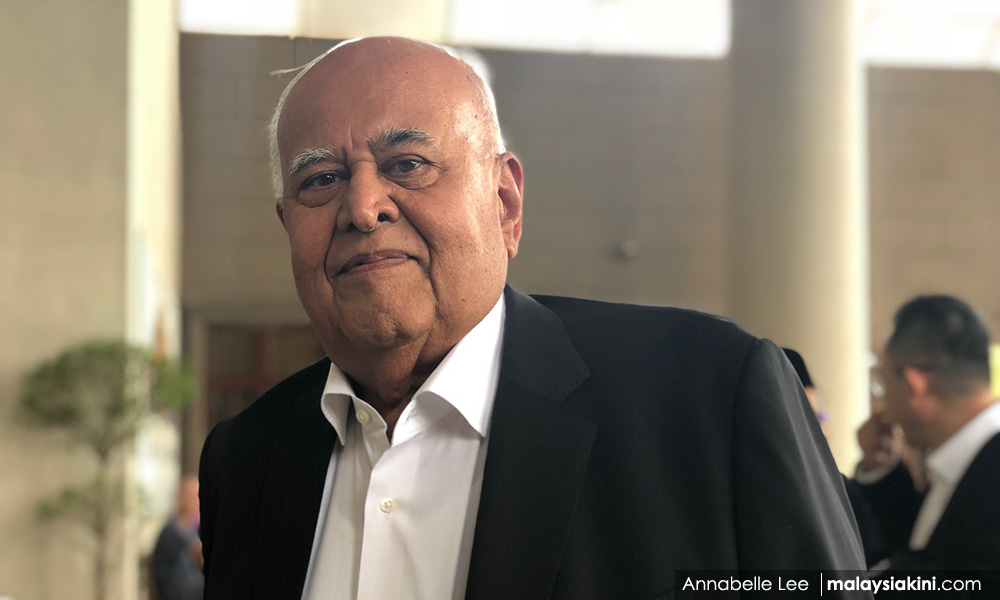

In the case of Kekatong Sdn Bhd vs Danaharta Urus Sdn Bhd, the Court of Appeal, speaking through constitutional jurist Gopal Sri Ram (above), held: "... that the fundamental liberties guaranteed under Part II of the Federal Constitution, including Article 8 (1), should receive a broad, liberal and purposive construction.

"If access to justice is to be a fundamental liberty, then it must be accommodated within Article 8 (1) of the Federal Constitution. Article 8 (1) is a codification of Dicey's rule of law. Article 8 (1) emphasises that this is a country where government is according to the rule of law.

"There must be fairness of state action of any sort, legislative, executive or judicial. No one is above the law.

"In Malaysia, it is not the law made by Parliament that is supreme, it is the Federal Constitution which is the supreme law. In Malaysia, the ultimate constraints upon legislative power are not political but legal, that is to say that any law passed by Parliament must meet the fairness test contained in Article 8 (1)."

The Court of Appeal in this case correctly followed the decision of the Federal Court in the case of Othman Baginda vs Ombi Syed Alwi Syed Idrus, where then-lord president Raja Azlan Shah said: "In interpreting a constitution, two points must be borne in mind. First, judicial precedent plays a lesser part than is normal in matters of ordinary interpretation.

"Secondly, a constitution, being a living piece of legislation, its provisions must be construed broadly and not in a pedantic way - with less rigidity and more generously than other acts."

In a similar vein, the Federal Court in Dewan Undangan Negeri Kelantan and another vs Nordin Salleh and another, rightly held that: "In testing the validity of state action with regard to fundamental rights, what a court must consider is whether it directly affects the fundamental rights or its inevitable effect or consequence on the fundamental rights is such that it makes their exercise ineffective or illusory.

"A constitution should be construed with less rigidity and more generosity than other statutes and as sui juris, calling for principles of interpretation of its own, suitable to its character, but not forgetting that respect must be paid to the language which has been used.

"In construing constitutional documents, it is axiomatic that the highest of motives and the best of intentions are not enough to displace constitutional obstacles.

"Whenever legally permissible, the presumption must be to incline the scales of justice on the side of the fundamental rights guaranteed by the constitution, enjoying as they do, precedence and primacy."

Origin of 'scandalising the court'

The contempt of scandalising the court has its origins in the case of R vs Almon which was decided in 1765. The Australian High Court in the case of The King vs Nicholls, declined to follow R vs Almon.

The judge said: "It is said... that they suggest a want of impartiality, but we do not find that in them, and I am not prepared to accede to the proposition that an imputation of want of impartiality to a judge is necessarily a contempt of court.

"On the contrary, I think that if any judge of this court or any other court were to make a public utterance of such character as to be likely to impair the confidence of the public, or of suitors, or any class of suitors in the impartiality of the court in any matter likely to be brought before it, any public comment on such an utterance, if it were a fair comment, would so far from being a contempt of court, be for the public benefit, and would be entitled to similar protection to that to which comment upon matters of public interest is entitled under the law of libel."

In the case of Baradakanta Mishra vs The Registrar of Orissa High Court and another, the Indian Supreme Court also expressed its doubts about R vs Almon in colourful language: "It is a moot point whether we should still be bound to the legal moorings of R vs Almon.

"In fact, there is grave doubt as to whether this species of contempt of court, namely, scandalising the court, should still be resorted to in this day and age, given the importance of fundamental constitutional freedoms, like freedom of speech and expression, and of the press in any democratic society.

In the case of MacLeod vs St Aubyn, the judge observed that: "Committals for contempt by scandalising the court itself have become obsolete in this country.

"Courts are satisfied to leave to public opinion attacks or comments derogatory or scandalous to them. Proceedings for this species of contempt should be used sparingly and always with reference to the administration of justice.

"It seems, therefore, that there are two primary considerations which should weigh with the court when it is called upon to exercise the summary powers in cases of contempt committed by scandalising the court itself.

"In the first place, the reflection on the conduct or character of a judge in reference to the discharge of his judicial duties would not be contempt if such reflection is made in the exercise of the right of fair and reasonable criticism, which every citizen possesses in respect of public acts done in the seat of justice. It is not by stifling criticism that confidence in courts can be created."

'Bona fide constitutional right'

This view was reflected again in the case of Majlis Peguam Malaysia and others vs Raja Segaran S Krishnan, where Sri Ram, in language of great clarity said: "Suffice to say that the defendants were exercising their bona fide constitutional right.”

In the New Zealand case of Solicitor-General vs Radio Avon Ltd, the Court of Appeal said: "The courts of New Zealand, as in the United Kingdom, completely recognise the importance of freedom of speech in relation to their work, provided the criticism is put forward fairly and honestly for a legitimate purpose and not the purpose of injuring our system of justice."

In Canada, the Ontario Court of Appeal (above) in R v Kopyto said: “The courts play an important role in any democratic society... As a result of their importance, the courts are bound to be the subject of comment and criticism.

"Not all will be sweetly reasoned... But the courts are not fragile flowers that will wither in the hot heat of controversy. Judges as persons, or courts as institutions are entitled to no greater immunity from criticism than other persons or institutions.

"Just because the holders of judicial office are identified with the interests of justice, they may forget their common frailties and fallibilities. There have sometimes been martinets upon the bench, as there have also been pompous wielders of authority who have used the paraphernalia of power in support of what they called their dignity.

"Therefore, judges must be kept mindful of their limitations and of their ultimate public responsibility by a vigorous stream of criticism expressed with candour, however blunt.

"Courts and judges must take their share of the gains and pains of discussion which is unfettered except by the laws of libel, by self-restraint, and by good taste.”

Dignity must rest on 'surer foundations'

The contempt of scandalising the court was long ago found to violate the US First Amendment constitutional rights of freedom of speech and of the press, and was dismissed as “English foolishness” by the US Supreme Court in the case of Bridges vs California.

In R vs Commissioner of Police of the Metropolis, judge Tom Denning said: “This is the first case, so far as I know, where the court has been called on to consider an allegation of contempt against itself.

"It is a jurisdiction which undoubtedly belongs to us, but which we will most sparingly exercise: more particularly as we ourselves have an interest in the matter.

"Let me say at once that we will never use this jurisdiction as a means to uphold our own dignity. That must rest on surer foundations. Nor will we use it to suppress those who speak against us. We do not fear criticism, nor do we resent it.

"For there is something far more important at stake. It is no less than freedom of speech itself. It is the right of every man, in Parliament or out of it, in the press or over the broadcast, to make fair comment, even outspoken comment, on matters of public interest.

"Those who comment can deal faithfully with all that is done in a court of justice. They can say that we are mistaken, and our decisions erroneous, whether they are subject to appeal or not.

"All we would ask is that those who criticise us will remember that, from the nature of our office, we cannot reply to their criticisms. We cannot enter into public controversy. Still less into political controversy.

"We must rely on our conduct itself to be its own vindication. Exposed as we are to the winds of criticism, nothing which is said by this person or that, nothing which is written by this pen or that, will deter us from doing what the occasion requires, provided that it is pertinent to the matter in hand. Silence is not an option when things are ill done".

This was approved by the Federal Court in the case of Lim Kit Siang vs Dr Mahathir Mohamad, where it was held at first instance by Harun J (as he then was), that: "The right of every individual (including the prime minister) to freedom of speech in this country has been consistently upheld by the courts subject only to any restrictions that are prescribed by the Constitution itself.”

The statements made by the lawyer and the Court of Appeal judge in his affidavit are already the subject of an investigation by the police and the MACC.

The government has agreed to form a royal commission of inquiry to inquire into the allegations of judicial misconduct and corruption. Therefore, the actions of the attorney-general, while seeming to be in the public interest, must be viewed with caution, since it has a chilling effect on freedom of speech and of the press when it comes to matters concerning the judiciary, where there are serious allegations of impropriety.

Fair and open criticism of the bench should not be criminalised in any progressive democracy, whatever the motives or purpose, so long as the intention is to uphold the Constitution and the rule of law.

Comment made in good faith, and in the public interest, should not be stifled by resorting to contempt powers.

GERARD LOURDESAMY is a senior lawyer and Malaysiakini subscriber/commenter.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of Malaysiakini.

RM12.50 / month

- Unlimited access to award-winning journalism

- Comment and share your opinions on all our articles

- Gift interesting stories to your friends

- Tax deductable