Malaysia, China, and why it's so important that we understand each other

COMMENT | I would like to take this opportunity to speak on two issues of great consequence:

First, the importance of Malaysia-China relationship to the region in this uncertain time of potential great power rivalry; and

Second, the urgent need to deepen Malaysia’s understanding of contemporary China, as well as China’s understanding of contemporary Southeast Asia.

Malaysia-China relations

In 1974, Malaysia was the first Asean country to establish formal diplomatic ties with China. It was a time when the United States was still deeply involved in the Vietnam War while Malaysia was still fighting the Malayan Communist Party’s insurgency.

For both Malaysia and China, 1974 was a major diplomatic feat.

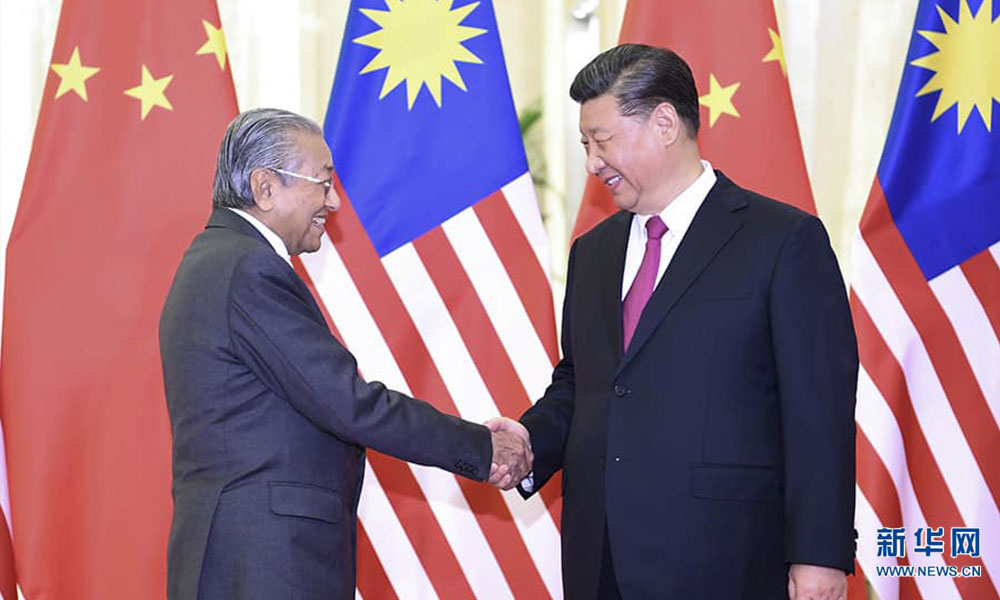

In the aftermath of June 1989 Tiananmen incident, China faced isolation internationally. From around 1990, Tun Dr Mahathir Mohamed, in his first stint as Prime Minister, initiated moves to bring China into engagements with Asean, providing China with a window to the world when other doors were still frozen in ice.

Despite being a small country, Malaysia under Mahathir has a record of being a “Third World” champion and doing the heavy lifting in global affairs.

Today, the question is, where are we now?

If the immediate period after the fall of Berlin Wall is called the “post-Cold War” period; we are probably at the “post-post-Cold War” period in which the world order that held the world together since 1989 is very much about to cease to exist in 2019.

We are at the end of an era. But no one is quite sure what is to come.

On the one hand, the world is a more complex, if not more dangerous, place because the US is no longer the singular superpower that underwrites international security.

Instead, the US now sees China and Russia as strategic competitors. Other middle powers such as Iran, Turkey, Japan, India, etc, are significant players as well.

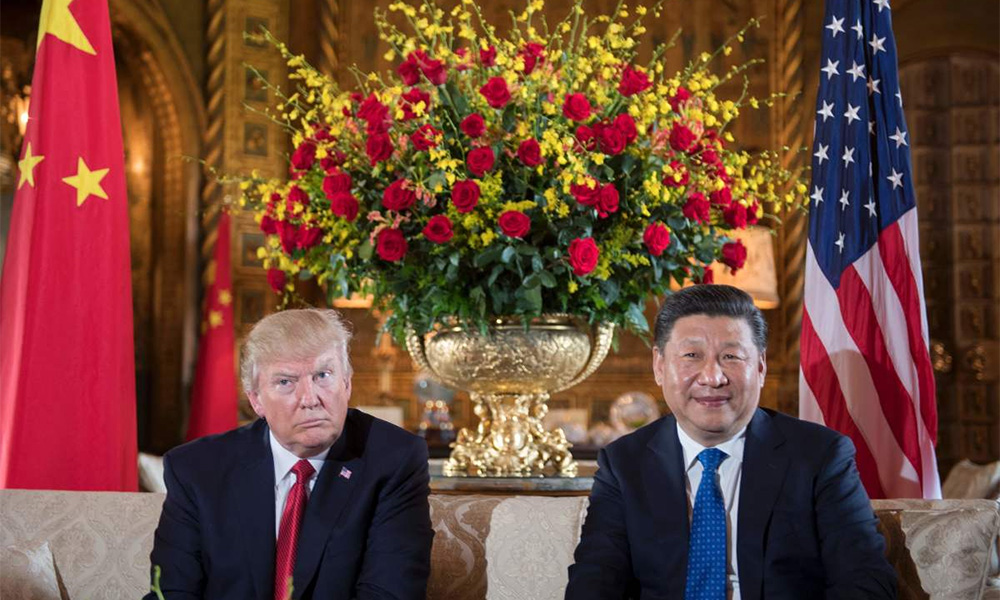

By now, we will have to accept that the US’ actions against China, be it a trade war or other hostilities, are not just President Donald Trump’s personal preference but reflect a deeper bipartisan sentiment in the United States, which will likely survive Trump’s tenure as president.

On the other hand, the complexities of the world mean we, even the relatively small Malaysia, gets a chance to shape the outcome of world events.

Malaysia since the 2018 general election has been an important international voice attempting to put forward a non-aligned position in a rapidly polarising world.

Besides Mahathir, our Foreign Minister Saifuddin Abdullah and Defence Minister Mohamad Sabu have repeatedly reiterated our position: we do not want to choose between the United States and China.

My friend Kuik Cheng Chwee probably called this “hedging” but I am of the view that we are less transactional.

Malaysia is pursuing an “activist neutrality” posture. We actively engage all sides in the fervent hope that the world is not split between China and the US.

The need to understand contemporary China

If Malaysia plays it's cards carefully, yet boldly, we can be the trendsetter in regional public opinion, just like in the case of Mahathir speaking up for Huawei recently.

Or, in the case of the Belt and Road Initiative, the renegotiation of deals with Malaysia post-2018 election probably encourages China to put more emphasis on financial transparency in future projects.

But for Malaysia to play this active middle power role through proactive diplomacy and advocacy, we will need to organise ourselves better as a nation to harness Malaysia’s potential.

Malaysia needs to understand contemporary China better and in a much deeper way.

Saifuddin and Education Minister Maszlee Malik, and I, have talked several times on the need to strengthen Malaysia’s research on China, Middle East, South Asia and Southeast Asia.

It is my hope that through public, private and community coordination, as a nation, over a period of 10 years, we can actively nurture at least 100 PhD holders of all ethnic backgrounds researching on contemporary China’s politics, economics and societies.

It doesn’t matter whether they graduate from China or the United States or Australia, so long as they eventually play a role in shaping public policy in Malaysia’s politics, civil service, academia, think tanks, corporations, etc, in the years to come.

Of course, we will need the institutional framework to sustain this.

I spent two years as a student of Chinese literature in a local college two decades ago.

While we may want to keep the studies of Chinese literature, we should emphasise on channelling a lot more public and community resources to the studies of contemporary China.

And if we can replicate the 100 PhD holders in 10 years for the studies of contemporary Middle Eastern, South Asian, Southeast Asian and to look at their politics, economics and societies, Malaysia will be a significant regional or even world leader in understanding the complex world that we are dealing with.

Malaysia can be a great meeting place of the greatest minds thinking about the future of the world.

For instance, some top Chinese scholars who specialise on the United States are now not allowed to enter United States while some US top scholars on China are finding it uncomfortable to enter China, worrying about a tit-for-tat situation.

They can all come here to meet in Malaysia and help develop our understanding of China and the world.

Avoid the role of bully

At the same time, China needs to radically change its approach to understand Southeast Asia better. For China to emerge as a credible benign great power, China will need to treat Southeast Asian states exceedingly well to prove to the world that China’s rise is no threat to the region.

China needs to realise that it is huge vis-à-vis smaller Southeast Asian nations. Much as China believes that it is the victim of bullying by the West, particularly the United States, China needs to do everything possible to prevent the perception of smaller states that China is a bully.

To get the policy mix right at all time, just as Malaysia needs to study China more, China needs to study Southeast Asians more too.

I am delighted that a total of five universities in China have a Malaysian studies centre. But if we are truthful to ourselves, just like Malaysia could have and should have done so much more to understand contemporary China, China will have to invest a generation of her best talents in understanding Southeast Asia.

Great power diplomacy (Da Guo Wai Jiao) is important to China, thus many of her best brains devote their lives on the understanding of United States, Russia, Japan and Europe, in the tense world of great power rivalry.

Now China needs to be agile and nimble in handling Southeast Asia. Southeast Asia is China’s most important gateway to the world that is open and possibly friendly, unlike in Northeast Asia where China is faced with US allies Japan and Korea.

One pitfall that China will have to deal with consciously is that most resources in China’s academia currently, when it comes to the research of Southeast Asian societies, is still devoted through Huaqiao studies, which will not lead anywhere.

In fact, China needs to do everything possible to avoid understanding Southeast Asian societies purely from the lenses of Huaqiao perspective.

The late great premier Zhou Enlai was very wise in his counsel that China recognises the ethnic Chinese diaspora in Southeast Asia as citizens of the respective countries and states, and not a special group of potential extraterritorial Chinese countrymen of sorts.

China’s academia needs to understand Southeast Asian nations in their entirety so to gauge them as accurately as possible.

The United States got Southeast Asia wrong during her ascendancy in the 1960s and got stuck in Vietnam for a long time, whereas, for contemporary China, the prize of understanding Southeast Asian nations means having more friends in time of global polarisation.

In conclusion, Malaysia-China relations is more than mere bilateral relations but potentially a trendsetter for others in the region and beyond.

To scale greater heights together, Malaysia needs to do more to understand contemporary China better while China needs to do more to understand contemporary Southeast Asia better too.

LIEW CHIN TONG is Deputy Defence Minister. This is his speech at the international forum in conjunction with the 45th Anniversary of Malaysia-China Diplomatic Relations in Sheraton Hotel, Petaling Jaya.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of Malaysiakini.

RM12.50 / month

- Unlimited access to award-winning journalism

- Comment and share your opinions on all our articles

- Gift interesting stories to your friends

- Tax deductable

Liew Chin Tong

Liew Chin Tong