The case for the constitutionality of vernacular schools

COMMENT | Recently, several groups and individuals have filed suits in court to declare vernacular schools unconstitutional. The argument mounted is that vernacular schools are publicly funded, and when they use Mandarin or Tamil as the main medium of instruction, this contravenes Article 152 which provides that the Malay language is the national language.

In my humble view, vernacular schools are constitutional. This is particularly so when one reads Article 152 of the Federal Constitution in totality and appreciates the historical context of vernacular education in Malaysia.

Protection of use of vernacular languages

Article 152(1) does say that the national language shall be the Malay language – there is no dispute about this.

However, there is an exception which is entrenched in Article 152(1)(a): “provided that no person shall be prohibited or prevented from using (otherwise than for official purposes), or from teaching or learning, any other language”.

It is clear that “using” any other language, besides the Malay language, is protected under the Constitution - provided it is not for “official purposes”.

The key question: can the medium of instruction in vernacular schools be categorised as an “official purpose”?

Article 152(6) defines “official purpose” as “any purpose of the Government, whether Federal or State, and includes any purpose of a public authority”. In turn, a “public authority” is defined in Article 160 as the Yang di-Pertuan Agong, a state ruler, federal government, a state government, a local authority, a statutory authority exercising powers vested in it by federal or state law, all the courts, or any officer appointed by or acting on behalf of such parties.

As one can observe, a vernacular school is not explicitly included as a “public authority”. But could it possibly be categorised as a “statutory authority exercising powers vested in it by federal or state law” within Article 160?

This is when the contentious Merdeka University case comes into the picture. In 1978, Chinese guilds and associations filed a petition to incorporate Merdeka University, which would use Chinese as a medium of instruction.

The education minister rejected the petition on the basis that it was contrary to the national education policy.

The matter was brought to court. In 1982, the Federal Court held that it was not unconstitutional for the government to reject the incorporation of Merdeka University. Its reasoning is as follows:

(i) A university has the requisite public elements – it is subject to some degree of public control in its affairs, involves a number of public appointments to office, acts in the public interest and is eligible for public funding.

(ii) A university is therefore a “public authority” within the meaning of Article 160.

(iii) A university is also a statutory authority exercising powers vested by it under federal law.

(iv) As such, having Chinese as a medium of instruction would be use of the language for an “official purpose”, which use may be prohibited under Article 152(1).

On the surface, it would seem that the Merdeka University case is a basis for arguing that vernacular schools are unconstitutional.

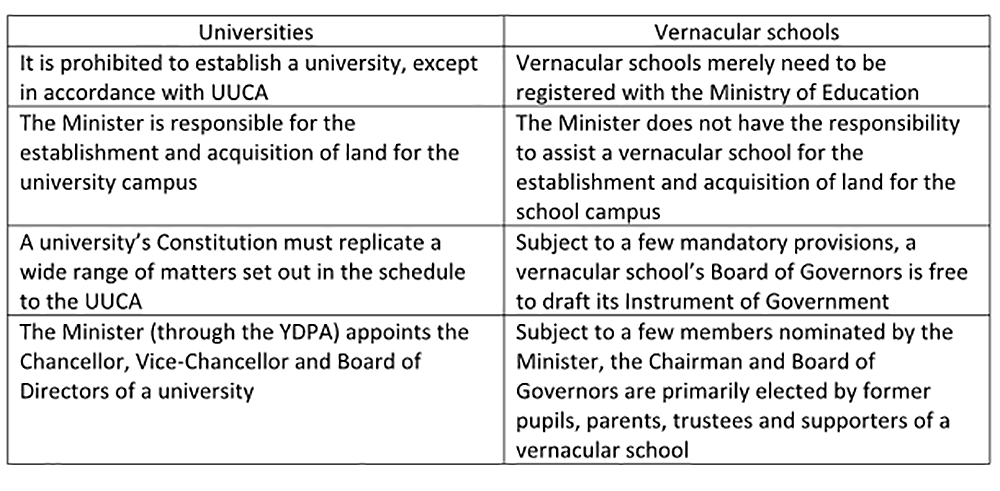

However, there are key differences between the two. Unlike a university under the University and University Colleges Act 1971 (UUCA), vernacular schools are governed quite differently under the Education Act 1996:

Pertinently, the Federal Court in Merdeka University was “greatly influenced by the scheme of the [UUCA], which is peculiar to Malaysia, in that it prohibits the establishment of a university within its context, except in accordance with its provisions (section 5), and that a university, when established thereunder, is deemed to have been established by section 7(1) thereof”.

In contrast, as highlighted above, there is no such prohibitive requirement for vernacular schools which merely need to be registered with the Ministry of Education under the Education Act 1996.

It is, at the very least, arguable that vernacular schools are not a “public authority” or “statutory authority” – therefore the use of Mandarin or Tamil as a medium of instruction is not for an “official purpose” and is protected under Article 152(1)(a).

Right of government to sustain use of vernacular languages

In the alternative, there is a second exception entrenched in Article 152(1)(b): “Nothing in this Clause shall prejudice the right of the Federal Government or of any State Government to preserve and sustain the use and study of the language of any other community in the Federation.”

In simple terms, if the federal government wishes, it has the power to preserve and sustain the “use” and “study” of Mandarin or Tamil in Malaysia. Such power is not only limited to the “study” of Mandarin or Tamil, i.e. purely Mandarin language classes. This power arguably also extends to the “use” of Mandarin or Tamil, i.e. using Mandarin as a medium of instruction to teach Science, as in vernacular schools.

For the vernacular schools suit, the cabinet has already come out in favour of the existence of vernacular schools. It has instructed the attorney-general to act accordingly. Hence, Article 152(1)(b) acts as an additional bulwark for the continuation of vernacular schools.

In the Merdeka University case, the government was against its incorporation. That is why the scope of Article 152(1)(b) was not explored in detail. The Federal Court may have decided differently if the government had supported the establishment of Merdeka University.

Our constitution

Finally, it can be implied that the drafters of our Constitution intended for the continued existence of vernacular schools that use Mandarin or Tamil as a medium of instruction.

In the years leading up to the drafting of our Constitution, the drafters must have been well aware of the contentious debate on vernacular schools through the 1951 Barnes Report, 1952 Fenn-Wu Report, 1956 Razak Report and the Education Ordinance 1957 – as well as representations by Umno, MCA and MIC from the Alliance Party.

Yet, the Constitution made no reference at all to the gradual abolition of the use of Mandarin or Tamil as a medium of instruction in vernacular schools.

Contrast this with the 10-year grace periods to transition from English to the Malay language for proceedings in Parliament and State Legislative Assembly (Article 152(2)), authoritative texts of Bills and Acts of Parliament (Article 152(3)) and superior courts (Article 152(4)). And for proceedings in subordinate courts, it shall be in English until Parliament provides otherwise (Article 152(5)).

If the drafters of our Constitution intended for such a similar transition for vernacular schools, they would have explicitly mentioned so in Article 152.

This is, of course, not indicative of my views on the relationship between vernacular schools on national unity – that is the subject matter of another long debate.

Suffice to say, the Constitution, in its present form, appears to protect the use of minority languages and the continued existence of vernacular schools.

LIM WEI JIET is a constitutional lawyer.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of Malaysiakini.RM12.50 / month

- Unlimited access to award-winning journalism

- Comment and share your opinions on all our articles

- Gift interesting stories to your friends

- Tax deductable