The meltdown of Pakatan Harapan

COMMENT | The events of the past 10 days might be quite bewildering to many Malaysians. Alliances have been forming and dissolving within hours and contradictory statements have been issued by various players.

But it starts making more sense when we look at the interests and intentions of the main players – former prime minister Dr Mahathir Mohamad, sacked PKR deputy president Azmin Ali, PKR leader Anwar Ibrahim and Bersatu leader Muhiyuddin Yassin.

Here’s my take on it.

Mahathir Mohamad

Mahathir is at the centre of the latest developments though I do not think that he wanted it to unfold at this point in time. Since the 1960’s, Mahathir has made no secret of his belief that for an ethnic group to succeed in the modern era it needed its share of scientists, bankers, professionals, business people and millionaires – a modern bourgeoisie!

In Mahathir’s assessment, merely preserving the old Malay elite comprising the feudal aristocracy, landlords and the royalty wouldn’t be enough for the Malays to hold their own in the modern world. There needed to be a Malay bourgeoisie. And he has spent the major portion of his life in developing this Malay bourgeoisie, by hook or by crook.

And to be fair to him, he has succeeded to a certain extent. There are now many Malay professionals, academicians, scientists, business people and millionaires.

However, Mahathir feels that there is still a need for the Malaysian state to continue playing an active role in promoting and building the Malay bourgeoisie given the vigour of the Malaysian Chinese business community, the rise of China and the predatory multinationals from the US, Europe and Japan.

And he is apprehensive that the Pakatan Harapan leaders - Lim Guan Eng and Anwar Ibrahim - will not do what is necessary to protect and promote the nascent Malay bourgeoisie. The former believes too much in the free market and is too cosy with Chinese capital, while the latter is too friendly with foreign interests and might agree to compromise the Malaysian state’s capacity to nurture the Malay bourgeoisie – for example by agreeing to the “Investor State Dispute” and “Government Procurement” clauses in the Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement and other similar trade deals.

So Mahathir, I think, was ambivalent about Harapan remaining in power for more than one term from the very start.

For him, Harapan represented the only way to remove the kleptocrats within Umno. He felt that Umno could not be reformed from within as those in power were too entrenched, so he needed to join up with DAP and PKR to cleanse Umno of the “crooks”.

But from the beginning, Mahathir felt that he could not depend on Harapan to safeguard and complete his lifetime project of creating and nurturing the Malay bourgeoise. He needed to pass the government to a Malay-majority government which would be committed to continuing the “Malay Agenda”. This is why he brought in MPs from Umno to bolster Bersatu, and why he cosied up with Umno and PAS.

It might also be the reason he promoted Azmin to become a federal minister – so as to weaken PKR by exacerbating the friction between Anwar and Azmin, so that if Bersatu could not be bolstered up enough to play a defining role in Harapan, the weakened Harapan would lose to Umno (cleansed of the worst kleptocrats) in the 15th general election.

This could also be the reason he didn’t countermand Lim’s decision in May-June 2018 to stop subsidy payments of RM300 per month to more than 70,000 traditional fishermen, and the rubber price support system that kicked in and supported 200,000 rubber smallholders each time the price of cup lump (scrap rubber) dipped below RM2.20 per kilogram.

Cabinet meetings take place weekly. It would have been a simple thing for Mahathir to highlight to Lim the political folly of cutting these subsidies given that Harapan had only garnered less than 20 percent of the rural Malay vote and Umno and PAS were going around canvassing the point that the government had passed to non-Malay control and that the well-being of Malays would be undermined.

However, Mahathir kept quiet on this issue, probably thinking to himself “Go ahead if you want to shoot yourself in the foot”.

I see Mahathir as a master politician with very clear aims – clean up Umno, and then ensure the administration of the country is back in the hands of those who genuinely support the agenda to protect and develop the Malay bourgeoisie. And, he has been transparent in his position with regard to the Malay bourgeoisie right from the 1960s.

Disclaimer: The fact I can see where Mahathir is coming from does not mean that I agree with his approach to building the Malaysian nation. And I haven’t touched on the harm he has done to the Malaysian poor of all races by his programme of privatisation. Nor have I brought in the various ways he seriously weakened institutions like the judiciary and concentrated power in the office of the prime minister as these important issues aren’t central to the power struggle that is taking place.

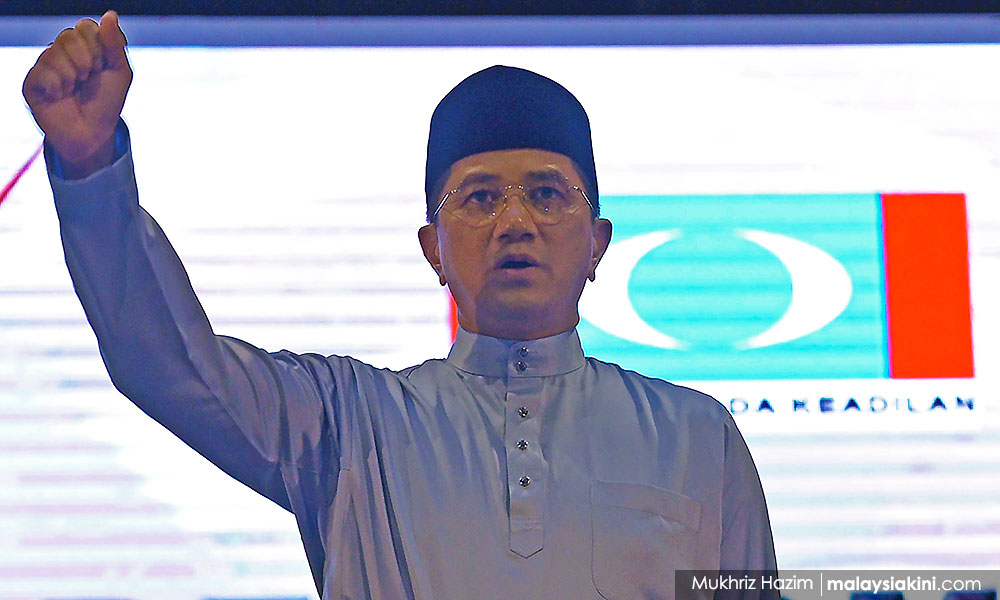

Azmin Ali

Mahathir’s plans were thrown into disarray by Azmin’s initiation of a coup on the Saturday of Feb 22. Azmin is now seen as the villain of the piece by many Malaysians as he set into motion the events that led to the unravelling of the Harapan government. But let’s take a look at the situation from Azmin’s vantage point.

Azmin was Anwar’s trusted lieutenant since the Reformasi days (1998). He did prison time because of his association with Anwar. He stayed faithful to the cause even when PKR did badly in 2004 and was cut down to a single seat in Parliament.

Azmin was there through the bleakest periods. But when the wind changed and PKR took five states in 2008, Anwar put Khalid Ibrahim, a former Umno man who had just crossed over to PKR a few months earlier, into the post of menteri besar of Selangor – a post that Azmin really wanted.

Why did Anwar do this? Azmin is intelligent, articulate and capable. He can run a state efficiently as his stint as menteri besar from after the “Kajang Move” clearly demonstrates.

Why wasn’t he given the post of menteri besar in 2008? I think it is because Anwar was paranoid about Azmin’s growing popularity within the party. Anwar feared that Azmin would emerge as a challenger to him if allowed to assume the powerful position of menteri besar of the richest state in the Federation. So, Anwar put Khalid – a newcomer without the extensive networks that Azmin possessed within the party - in the menteri besar post.

Anwar’s attempt to “contain” Azmin did not end there. At every PKR election - 2010, 2014 and in 2018 - Azmin went for the deputy president position. He never challenged Anwar or former deputy prime minister Dr Wan Azizah Wan Ismail for the post of party president.

But Anwar always kept backing challengers to Azmin - Zaid Ibrahim in 2010, Saifuddin Nasution Ismail in 2014 and Rafizi Ramli in 2018 - but tellingly, they all lost.

When the Kajang Move backfired in 2014 and Anwar was not able to take the position of menteri besar, again Anwar attempted to block Azmin ascent to the post, but on this occasion, Azmin managed to outfox Anwar and served as a fairly competent menteri besar.

The elevation of Azmin to the powerful portfolio of economic affairs minister after the 14th general election further exacerbated the tension between him and Anwar. Was this an innocent appointment, or was the master tactician setting the scene for the weakening of PKR?

For Azmin (above), the outcome of the meeting of the Harapan Presidential Council on Feb 21 was a disaster. It meant that Anwar would probably become the prime minister within a year. Given Anwar’s vindictiveness towards Azmin, the latter's ally Zuraida Kamaruddin and team, Azmin felt he had a lot to lose when that happened.

So, he launched a pre-emptive strike.

However, Azmin had seriously misread Mahathir’s game plan.

Azmin could see that Mahathir was working to increase Malay dominance in the government. But he didn’t realise that for Mahathir, cleansing Umno by removing the kleptocrats was a non-negotiable issue. It had to be done before power could be passed back to Umno.

So of course, Mahathir was upset – both with Azmin and with Bersatu. The coup had come too soon. The ascension of Umno to ruling position might lead to the watering down of charges against the very people he came out of retirement and worked so hard to excise from Umno. Mahathir’s flip-flops in the week after the coup are quite understandable if viewed from this perspective.

Anwar Ibrahim

Another leading if not tragic figure in the current saga, Anwar, has made huge contributions to Malaysian politics. In 1998, after his expulsion from government, he combatted Mahathir not by using the race card or religion (which he could have, as he was recognised as leader of the Angkatan Belia Islam movement), but by focusing on governance, fighting corruption, asking for justice for all and welfare for the poor.

He is well-read and his views on Islam are much more inclusive of non-Muslims. After 50 years of independence, he brought a new discourse to the political scene, and it had wide resonance with both Malays and non-Malays. This discourse still remains a viable foundation of a “Malaysia Baru” that many Malaysians hope for.

Anwar has also paid a huge personal price for challenging the Umno political establishment. He was stripped of his deputy premiership, charged for sodomy and humiliated publicly, jailed twice after trials that did not seem quite fair. He has sacrificed quite a bit.

But he has his serious flaws.

He has had a lot of difficulty in keeping his friends and allies with him. Apart from Azmin there are several other political leaders who, after working closely with Anwar for a period, parted company most acrimoniously – Khalid, Chandra Muzaffar, S Nallakaruppan, Zuraida, and many others.

So it is not just Azmin – only he stayed on much longer than the others. It is no secret that many PKR leaders, including a score of PKR parliamentarians, who were formerly loyal to Anwar but took Azmin’s side in the power tussle between the two.

I do not believe that it was because of monetary considerations. I think many of them had issues with Anwar’s leadership style – making unilateral decisions, undermining democratic institutions within the party, using henchmen to bend or even break the rules – all driven by a certain degree of paranoia (which has now become self-fulfilling).

Mahathir never recanted his statements in 1998-1999 that Anwar is not a fit person to be the prime minister of Malaysia, though he has always said that he would keep to the promise he made in 2018 to hand over power because a promise is a promise.

Anwar had a chance to form the government at mid-week, but could only garner the 92 MPs from DAP, PKR and Amanah. The leaders of Bersatu, Warisan and GPS were unwilling to support Anwar's premiership.

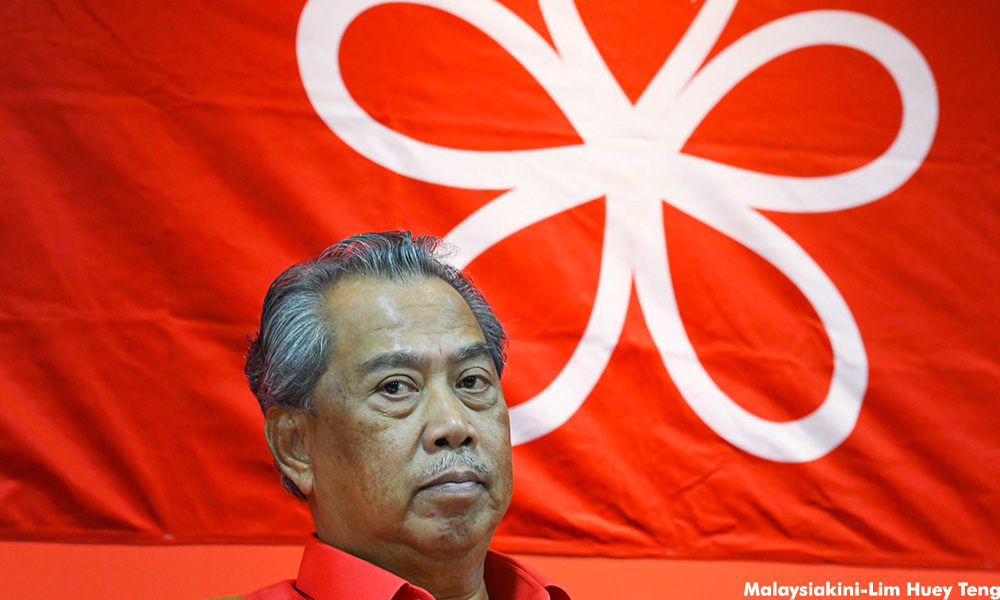

Muhyiddin Yassin

Muhyiddin’s role in this coup attempt is intriguing. Here is a man who was sacked from the post of deputy prime minister and from Umno because of his opposition to the misuse of public funds by the then prime minister. He teams up with Mahathir and contests the elections as part of Harapan and his party is rewarded quite richly in terms of cabinet positions. Yet he breaks from Harapan and teams up with Umno leaders including those who played a role in sacking him.

What is driving Muhyiddin and the Bersatu team to re-join a coalition that includes the very people they rebelled against not so long ago? Assuming Muhyiddin and the Bersatu team are acting rationally on the basis of their perception of the situation, what could be the main elements of their collective perception?

I can offer two – the first is that Harapan is a losing wicket as far as building Malay political support is concerned. Staying on as part of Harapan would be political suicide for a party contesting in Malay-majority constituencies.

The second, linked to the first, is the perception that Harapan is undermining the “Malay Agenda” as it is committed to “meritocracy”, trimming subsidies to poorer sectors, promoting market-based solutions and downsizing the public sector. Unease with Anwar’s leadership style might be yet another reason.

In retrospect

In retrospect, it is clear that Harapan has lost the propaganda battle for the hearts and minds of the Malay population.

None of the Harapan parties had grassroots-level networks that could rival PAS and Umno, so they were not able to effectively counter Umno propaganda that Harapan was “anti-Malay”.

It would have been possible for Harapan to have canvassed more actively for Malay B40 support.

For example, Harapan could have kept the allocations for the rural B40 constant but ensured full transparency - the amount budgeted for each type of aid for the rural population put up in the internet so that the local communities could monitor the implementation of the various projects - repairing houses, building PPR houses, repairing suraus and community halls, et cetera. This process remains opaque up till now and the local population is unable to check whether a percentage of the allocation is siphoned out by the local elite.

Ensuring transparency and mobilising the local communities to monitor the implementation of the projects for them would have been a huge eye-opener; especially if after a year the party and by extension workers compared the number of projects completed with the previous year’s and pointed out that the total allocation remained the same.

That would have immediately drawn attention to the fact that under the previous administration there must have been a lot of leakages.

Similarly, in urban areas, Harapan workers could have had meetings with low-cost flat residents documented the maintenance work and repairs needed and applied to the local government for the funds to do these necessary repairs.

A huge percentage of our urban B40 live in these high-rise slums. Efforts to clean up these flats and make them more inhabitable would have won a lot of support for the Harapan government. The amount that would have been needed would have been quite affordable for the federal government.

Our elderly are struggling with depleted savings. A Universal Pension Scheme of RM300 per month to all those above the age of 70 and without pension of any sort and assets of less than RM100,000 would have touched a whole lot of families and won the Harapan much support. It will only cost about RM3 billion per year, but would have brought much relief to the elderly.

If the above strategies had been followed, Harapan would now be in a position to challenge the usurpers to dissolve Parliament and have a re-election. Harapan daren’t do that now as there is a high possibility that they would lose a vast majority of its Malay-majority seats to Umno-PAS.

There was a lack of sensitivity in Harapan to the fact they only had obtained about 25 to 30 percent of the total Malay ballots cast in the 14th general election – a case of living in denial? That they would have to work hard to counter the propaganda that Umno would throw at them?

There were insufficient attempts to forge a consensus within Harapan as to how best to assuage Malay anxieties and win their support.

There were some in Harapan who acted on the assumption that the lazy Malay who had been spoilt rotten by subsidies thrown to them (“dedak”) by BN – such that they had developed a “subsidy mentality” and an “entitlement syndrome” from which they needed to be weaned. It was a shallow chauvinistic assessment and a very costly one at that.

This entire episode underlines the fact that many Malaysians are still stuck in their ethnic silos.

The political process that has been powered by ethnic-based parties has shaped the narrative of “us against them” that many Malaysians subscribe to. Can Malaysia ever get the reforms that we need if we do not reach out to the “other”?

A good way of starting down the road of inclusive politics is to find out more about poverty groups among the “other” and work with them towards the resolution of their problems.

Harapan could have adopted the so-called “Malay Agenda” and continued with the twin objectives of eradicating poverty irrespective of race and addressing ethnic imbalances in the modern sectors of the economy – aren’t these policy objectives that all fair-minded people would agree to?

And Harapan could have done it more efficiently by closing off the loopholes that allowed certain among the elite to plunder these allocations for their own benefit. These twin objectives are important for the creation of a more equitable and stable society and Harapan should have taken ownership of that project, tweaking it a little to make it inclusive of the non-Malay poor as well.

They would then have been in a much better position to weather the current political storm.

In the final analysis, we, the ordinary citizens, are also to blame for being too complacent and for failing to address the anxieties and insecurities fanned by decades of ethnic-based politicking. For not liberating ourselves from the stereotypes we hold about other ethnic groups. For not being more sensitive to the problems faced by others. For not doing more to reach out across the ethnic divide.

We need to learn from this debacle and continue working towards a more inclusive and equitable Malaysia. We should never give up and we should take heart from the fact that there are people of goodwill in all ethnic groups – people who would like to see justice and harmony prevail in the country.

Let’s identify with each other and work together for the long-term project of building a better Malaysia.

DR JEYAKUMAR DEVARAJ is the chairperson of Parti Sosialis Malaysia and former Sungai Siput MP.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of Malaysiakini.

RM12.50 / month

- Unlimited access to award-winning journalism

- Comment and share your opinions on all our articles

- Gift interesting stories to your friends

- Tax deductable