COMMENT | 'Like a kid seeing Santa Claus' – a frontliner reflects on getting vaccinated

COMMENT | I still remember the day I got the email that said “Sankaran, orientation in the Ricu tomorrow at 7am.”

“There we go,” I told my husband, “Covid-19 ICU orientation begins tomorrow.”

“Well,” he said. “We knew it was coming. Be careful. Protect yourself. Never let down your guard. You need to think like a soldier going into a warzone.”

“I know,” I replied. “Except this time the enemy is invisible.”

I am an anesthesiologist in the USA. In early March I was working at a large University Hospital in the Midwest. All elective surgeries were cancelled, and we were being redeployed to areas that needed our expertise. Covid-19 was exploding in the communities around us, especially in the surrounding cities.

Other hospitals were full; therefore, our university hospital opened the Ricu, also known as the Regional Infection Containment Unit. A state-of-the-art facility with 32 specially built negative pressure isolation rooms.

I was nervous, but I was also excited. This illness is something that we have never seen before and I was getting to be part of the fight against it, but I was also scared for myself and my family. I didn’t really know what to expect.

That morning, I put a lot of thought into my actions before I left home. It is typical for me to carry a big handbag with everything from snacks to Chapstick to phone chargers. That day I left home with nothing but my ID badge, my clothes, which I would later change into scrubs at the hospital, and my phone. This was sealed in a Ziplock bag that I could easily clean it with bleach wipes. That was it.

We still did not know how contagious the illness would be and how adequately we were protected against it.

So I got into the elevator and pressed the button for the 12th floor. There was only one other person in the elevator that morning and the title on his with coat read “Infectious diseases consultant”. We looked at each other knowingly. We both knew what going to the 12th floor meant. That we were going to the Ricu.

Futuristic surroundings

When I got there, it was like being in the medical bay of Star Trek. After registering with the clerk, you then badged into a vacuum chamber between two double doors. You had to wait until the outer door is closed before the inner door would open to let you into the Covid-ICU section.

At Ricu, we were orientated on SOPs. It was very different from anything I had experienced, although as an anesthesiologist I was used to taking care of very sick patients – both those going into surgery and those recovering from it.

A big part of our daily job involves managing ventilators, administering medications, blood and intravenous fluids when taking care of patients undergoing surgery. Anesthesiologists are skilled in essential procedures used in intensive care, such as putting in breathing tubes, performing bronchoscopies, placing central lines in the neck veins of patients and monitoring lines in their arteries.

These are skills we normally use if a patient is undergoing major surgery, like a heart bypass on a life support machine. As such, our expertise is well suited to looking after critically ill Covid patients.

Patient care was different with Covid-19; largely due to the fact these patients were in isolation, without any family members by their bedside.

Every day we would be assigned several patients to look after. The patients were in housed in negative pressure rooms – which are set up so that the air is sucked out of the rooms constantly, rather than being re-circulated.

You had to minimise going in and out because you would not want to break the vacuum. Often, if the patients were conscious, we would call into the rooms and talk to them. Sadly, however, most were unconscious, extremely unwell, in medically-induced comas and hooked up to ventilators.

To enter the rooms, we would have to fully garb up. This included wearing the now ubiquitous N95 mask. We are tested for the type that specifically fits your face to create a seal.

If you ‘fail” the fitness test, you get fitted with a PAPR (powered air-purifying respirator) hood instead. These are much more comfortable the N95 masks, but the numbers were extremely limited so most of us had to settle for N95 masks instead.

These masks strap tightly to your face with two elastic straps – at the end of the day, I always had a headache. There are many photos circulating on the internet of healthcare workers with pressure sores from wearing these for hours on end.

We would only enter the rooms if the patients were very unwell, close to having a cardiac arrest or needed an essential procedure such as “proning”.

This meant flipping an unconscious patient to lie on their front to improve the oxygen flow to their lungs. When a patient is hooked up to multiple machines this simple act requires at least five healthcare workers to do safely.

Some healthcare workers had hazmat suits but most of us put on an N95 mask with a second surgical mask on top, a face shield, two surgical gowns, two pairs of gloves. As you can imagine we were just sweltering – which made it very difficult to comfortably perform procedures such as placing dialysis lines.

I would be very drained and dehydrated at the end of a shift.

Unforgettable camaraderie

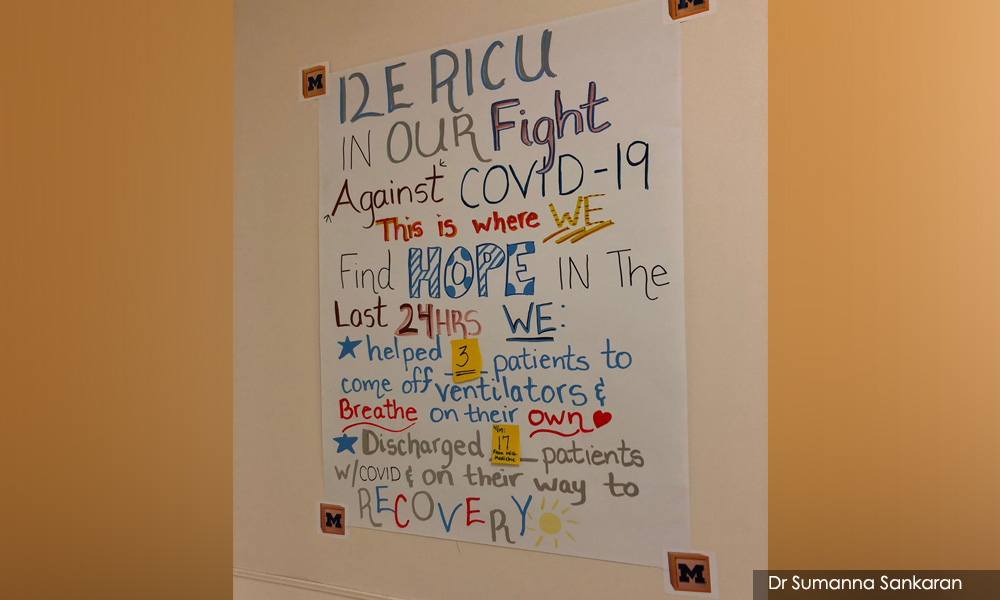

The RICU had very good camaraderie and our local community really bonded together to give us support. In addition to motivational greeting cards and drawings, we received multiple deliveries of food from the finest restaurants in our city.

We had a patient’s family send weekly pizza deliveries to our unit. We were so well fed to the point where I gained about 10 pounds in my two months in the ICU!

Everyone was great at keeping each other’s morale up. The families were so grateful even when we had difficult phone conversations – one family member who used to pray for me and all the staff on our unit every day despite the fact there was very little hope for her son’s survival.

What struck me the most about sickest patients I looked after was that a lot of them were like my husband and my brother-in-law – they were regular men in their forties and fifties.

Given the norm in America, some of them were obese. Other were pre-diabetes or just had mild asthma as an underlying condition. Prior to getting Covid, they were going all about their daily lives as normal. Many had families to support including young children at home.

It seemed like these men were the ones that were getting the sickest; needing the highest level of life support, having sudden blood clots and heart attacks out of nowhere, their kidneys failed, and they needed dialysis – and that was hard to deal with emotionally.

One night shift, I was with a patient who had just had a cardiac arrest. I was on Facetime with his brother wearing my full protective gear. I was trying to show his brother all the tubes and all the lines going into this man connecting him to machines. He was on about eight different medical infusions attached to his neck line and I was explaining that we needed to put another neck line in to put him on a dialysis machine. The last time this man had seen his brother he had been walking, talking, interacting like normal and now he was being kept alive by machines. And he was only allowed to see him through a screen.

Even I was no longer working in Covid ICU I kept following that patient’s progression. He made it out of ICU briefly but unfortunately, when I checked on his chart a couple of months later, I saw that he had indeed passed away.

That gives you really mixed emotions because you do everything you can – and it makes you think – all for what?

This man just spent two months of being poked and prodded, hooked up to machines, and eventually he died anyway.

That was hard. But it was not all bad. There was a woman who was a nurse whom I managed to discharge straight home from the ICU! That was a success story to remember.

Every day after a shift I had this routine where I came home and stripped off to my underwear in the basement by the washing machine and rushed past my very confused dog, had a shower and put on new clothes before I could come down and not feel like I was carrying Covid everywhere.

Covid has affected people in so many ways. It really makes you value the people around you and count your blessings every day.

What can I say about Covid in America? This great democracy is built on freedom of speech, freedom of movement, the right to express your opinions and to do what you want with your own body. However, when it comes to stopping the spread of Covid, these very ideals become a hindrance. People are not as easily regulated by the government as they are in other countries and value their freedom above all else. Sadly, however, this has made Covid spread like wildfire across the nation.

When the vaccine arrived

Fast forward a few months. I’m working in an inner-city hospital. I’m back in the operating theatre, not in Covid ICU any longer but the disease is still rampant in the community.

My hospital currently has more than 100 Covid positive patients, including up to 20 patients ventilated in the ICU. Now we are dealing with the problem of trying to get the long-term Covid ICU patients who are dependent on ventilators, dialysis and tube feeding out of the hospital. I look after them in the operating room as they undergo procedures where they have feeding tubes inserted into their stomachs to enable them to have the nourishment they need.

Many also need tracheotomy devices. These are small tubes that go into the front of the necks and connect to the windpipe. This enables a patient to be ventilated long term while the body gains the strength for the person to breathe on his or her own, without a machine. This tends to be a long process.

Yesterday we had four patients undergoing this procedure. I would not wish this on anyone.

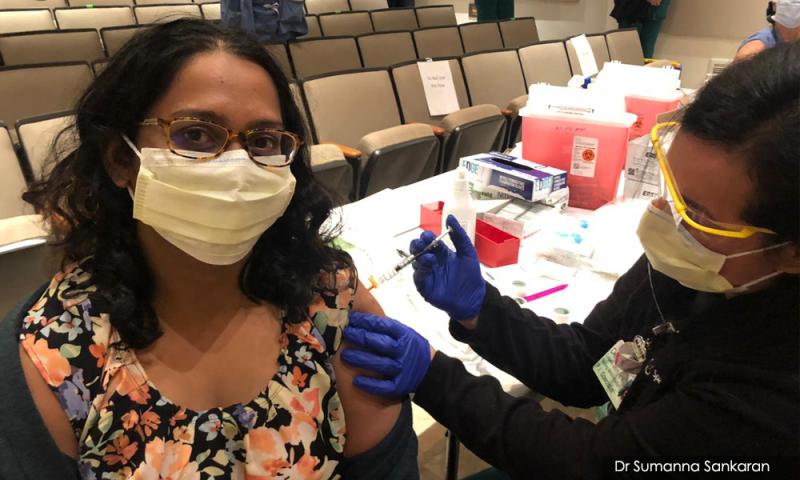

But there has been a major difference in my life: the week before Christmas I received the Pfizer MNRA Covid-19 vaccine.

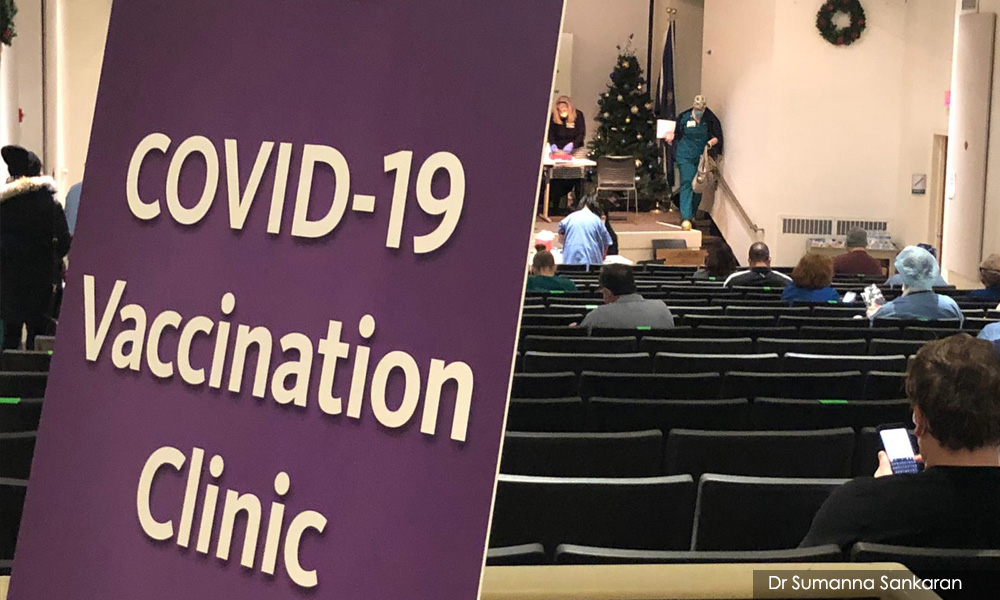

It was a euphoric moment. My hospital had a very festive atmosphere going on in the auditorium where the vaccine clinic was being held. It was decorated for Christmas and there were carols playing on the loudspeaker. It felt like I was a kid going to see Santa Claus. We all queued six feet apart and waited patiently and it took me about an hour to get my turn. There was a matronly woman taking pictures which made me feel like a celebrity. I didn’t even feel the needle go in because I was just happy that I was getting the vaccine.

I do think that from now on, whenever I need any kind of jab, maybe the flu jab, I’ll just distract myself by taking selfies because it really did seem to make me not feel the pain at all – so busy posing. I felt great. I felt relief.

I felt a sense of gratitude as a healthcare worker in the USA that I was one of the first few in the world that was offered the vaccine, and I am counting the days till I get my booster shot, which is already scheduled for Jan 8; which also happens to be my husband’s birthday.

Is there a reduction of layers of face masks, face shields, gowns and others? No, because we don’t know if being immunized prevents us fully from being carriers of the virus, so I don’t know if I could still bring it home.

Still, keeping it vigilant is definitely a huge relief that the end is in sight for us.

Thank you, science!

I’ve never been somebody who liked spending time in the labs in medical school – all those boring experiments never interested me. But some dedicated people spent a lot of time in a lab somewhere in order to develop the vaccine, so I’m incredibly grateful to these brilliant minds!

A lot of people have asked me – how do you feel? What about side-effects? Well, I finally felt that sense of euphoria and relief and stayed up baking cookies all night. Yes, my arm was sore and maybe a bit achy the next day, but I am looking forward to my second dose.

I am so looking forward to being able to travel again and see loved ones.

One of the first things I will do after I am vaccinated is to book a flight to see my family in Malaysia. I have not been to Malaysia in four years.

I also have a close friend in the UK who postponed his wedding because of Covid and I’m hoping to be able to attend that next year.

So 2021 gives us hope that we can finally reunite with our loved ones. Meanwhile, we will continue to take precautions, wear masks and wash hands and make do with video chats for now.

DR SUMANNA SANKARAN was born in Petaling Jaya and grew up in Subang. She left Malaysia at the age of 18 to attend medical school in Nottingham UK. She now lives in Michigan with her husband Brian, stepson Zane and Roxie the dog.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of Malaysiakini.RM12.50 / month

- Unlimited access to award-winning journalism

- Comment and share your opinions on all our articles

- Gift interesting stories to your friends

- Tax deductable