Loggers with cash in hand divide Kelantan Orang Asli community

An Orang Asli in Kelantan, Jimi Angah, is adept at living off the land. After all, the forests have provided sustenance for indigenous people like him for generations. The Temiar tribe he belongs to is one of the largest of 18 Orang Asli groups.

Being offered a bag of cash from a stranger out of the blue was the last thing Jimi expected one morning in 2021.

The 46-year-old father of nine remembered his surprise when a man approached him in his village and even called him by name.

“You’re the chairman of the Kampung Keturunan Tanah Wilayah Kampung Wuk, aren’t you?” Jimi recalled the man asking. “Would you like anything from us?”

As a community leader in his village, Jimi could tell at a glance the stranger wasn’t from those parts. The man spoke and dressed like a “Chinese towkay”, said Jimi.

Suspicious of the man’s intentions, he politely declined.

Not taking no for an answer, the man grabbed Jimi by the wrist and guided him down the hill to a Toyota Hilux parked just outside the village. Jimi said he felt deeply uncomfortable as the man opened the back door of his car and showed him a bag.

“I have offered this to the village just up the road from yours,” Jimi recalled the man saying. “They’ve taken it and asked for even more money! I can give you houses, piped water and money.”

It then dawned on Jimi what this was about - logging companies had been offering money and development to villagers, in return for access to cutting down swathes of trees on protected ancestral land.

The playbook unfolding before him was painfully familiar with what had occurred to other indigenous communities he knew of.

The man was insistent. Jimi stood his ground and again, politely declined.

“I rejected everything that was offered,” Jimi said. He did not want to sell his land and his people’s way of life to anyone.

But deep down, Jimi was troubled. He knew of many stories of communities evicted - sometimes violently - when they refused to make way for logging companies.

External pressures, internal strife

Since 2010, activists of Jaringan Kampung Orang Asli Kelantan (JKOAK) have been pushing back against logging, mining and plantation operations that encroach into their forests, villages and traditional way of life.

They have set up numerous road blockades to try and stop these operations. At times, confrontations turned hostile and put their lives at risk.

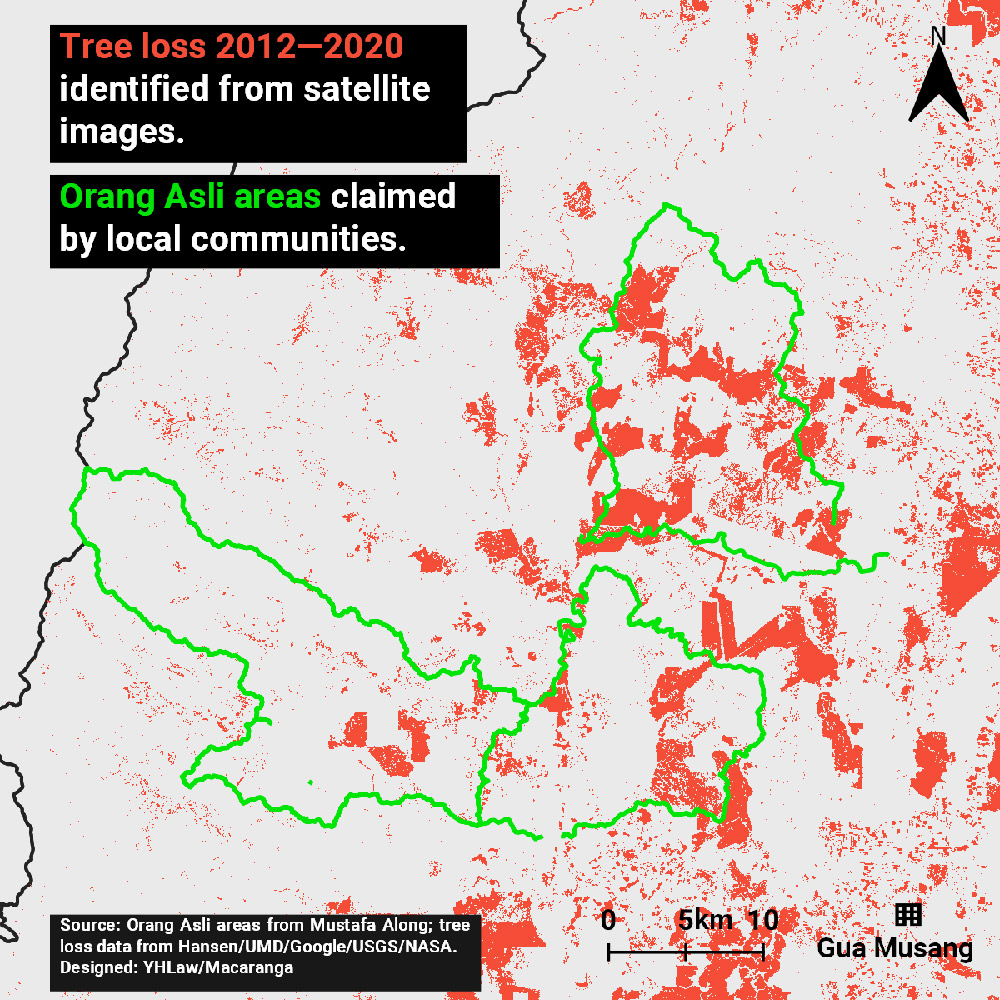

In a high-profile incident in September 2016, JKOAK activists tried to block a road to prevent a logging company from clearing land in a disputed area in the Gua Musang district of Kelantan.

After a tense standoff, a man used a chainsaw to destroy the bamboo structure set up, even as the activists clung to it. Three of the activists were briefly detained in a truck and threatened with arrest.

The blockade was eventually demolished by the loggers. Three lorries, loaded with logs, bulldozed over what was left of it.

In the chaos, the activists said, an unidentified person emerged from one of the loggers’ vehicles and fired two gunshots.

No one was injured. The blockade was just one of many attempts by the activists over the years, most of them in vain, against powerful companies and state authorities that grant them licences.

To compound matters, another challenge is growing from within the Orang Asli, causing factions in the fight for customary land rights. Villages have been accepting payments in return for development and access to amenities.

Out of more than 20 large villages that the JKOAK identified, at least eight of them have populations that are “pro-logging”.

They live on the outskirts of the forests and see no real value in their connection to them. They see the development offered by large companies as a way to improve their lives.

From extensive discussions with affected villages, JKOAK understands their village leaders have accepted money from these companies to enable access to ancestral land. But the amounts were not enough to be distributed to everyone and ended up only benefiting a few.

Those against the encroachment of customary land see such payments as bribery. As the incidents grew more frequent, one village tried to fend off a logging company’s advances by reporting it to the MACC.

Unclear application of law muddies waters

In June 2016, led by Musa Nor Apat and Anjang Rangget, a Temiar community in Kelantan lodged a report with the MACC.

They accused a logging company of trying to bribe their people in return for smooth passage to conduct logging operations on their customary land.

The two Temiar leaders said the company’s representative left RM1,000 and food items outside the customary hall in their village, after failing to convince anyone to accept them.

The incident occurred after another indigenous community carried out large-scale protests and roadblocks to prevent a logging project.

This convinced Musa and Anjang that the company was trying to prevent similar resistance from their people by offering cash and food.

To their disappointment, the MACC found no case for bribery against the company, as there were no official documents to prove the land belonged to the Temiar villagers.

Without proof of land ownership, the logic was that the villagers could not be bribed for something they were not authorised to approve anyway.

At the heart of the contention - while some perceive such payments as bribes, others see them as compensation out of goodwill.

Kelantan’s laws

Yogeswaran Subramaniam is familiar with how the letter of the law works against the Orang Asli.

The Malaysian lawyer and academic has specialised in research about Orang Asli land rights in Peninsular Malaysia since 2006. He has also acted as a pro bono legal counsel in significant court cases involving customary land rights issues.

Yogeswaran said the MACC’s decision was not wrong but “narrow”, as it overlooks critical issues the indigenous people are up against when proving ancestral land rights in the court of law.

Malaysia’s Federal Court - the highest and final appellate court in the country - already recognises the customary land rights of the Orang Asli. Yogeswaran cited court rulings such as the Sagong Tasi and Adong Kuwou cases as examples.

This protects the Orang Asli under common law, whereby laws are developed based on preceding rulings.

But in Kelantan, the state government has followed what is known as the written law, based on statutes. It does not follow decisions in earlier rulings.

This puts the burden on indigenous people to provide extensive findings in each case to prove their right to disputed areas. Most of them cannot afford to take on the laborious and long-drawn process.

“The problem is that the Kelantan state government only looks at the written law. They willfully disregard the principles and decisions of the Federal Court that state the rights of the Orang Asli to their generational land,” Yogeswaran said.

The reason for the Kelantan government’s position, he added, was to exert more control over the Orang Asli land and use it in ways that they deem fit. Logging operations generate revenue for the state, even if it compromises indigenous land rights.

This also runs contrary to the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), of which Malaysia became a signatory in 2006.

The UNDRIP is a key international instrument that provides for the recognition and protection of indigenous lands, territories, and resources.

Yogeswaran lamented that Malaysia has failed to consistently implement the principles it signed up to.

“Over the years, we’ve seen that clearly there is no political will to protect the customary land rights of the Orang Asli in Peninsular Malaysia,” he said.

“It is not a priority of the government.”

The Kelantan Menteri Besar’s office and the Kelantan Forestry Department did not respond to requests for comment.

Hope in the struggle

Despite the adversity, sporadic victories give the Orang Asli hope.

In 2017, supported by the JKOAK, an Orang Asli community won a six-year legal battle against the Kelantan government and State Land and Mines Department.

The High Court granted the community rights to over 9,300 hectares at Pos Belatim, in Gua Musang. It also revoked an agreement signed by the Kelantan government to develop a site in that area.

While these hard-fought wins put their plight in the spotlight, Yogeswaran said there can only be a long-term impact if the public sees the Orang Asli as an asset for Malaysia. He sees a critical role for them in nature conservation projects that contribute to the economy.

“If we can give this conservation an economic value, there is no way anyone will dare encroach on the Orang Asli land,” he said.

Back in Kampung Wuk, Jimi had only fighting words for those attempting to take land from the Orang Asli.

“We will reject these advancements (by developers) to the bitter end. That is how we’ve won case after case in court and got our rights back… because, for us, our land is more valuable than any money they can offer.”

Besides taking on outsiders, the JKOAK continues to stress the importance of dialogue between the pro and anti-logging factions within the Orang Asli.

Any success in protecting their ancestral land could well hinge on how the two camps see the way forward for their lives and livelihoods.

The writers are part of Jaringan Kampung Orang Asli Kelantan (JKOAK). This story was produced with the financial support of the European Union in the form of a grant from Internews Malaysia. The contents are the sole responsibility of Internews and do not necessarily reflect the views of the European Union.

RM12.50 / month

- Unlimited access to award-winning journalism

- Comment and share your opinions on all our articles

- Gift interesting stories to your friends

- Tax deductable