'I scammed so I could live': South Asians enslaved in scam compounds

A memory from 2022 sent a chill down Mohammad Abdus Salam’s spine sharper than a bone-biting Dhaka night.

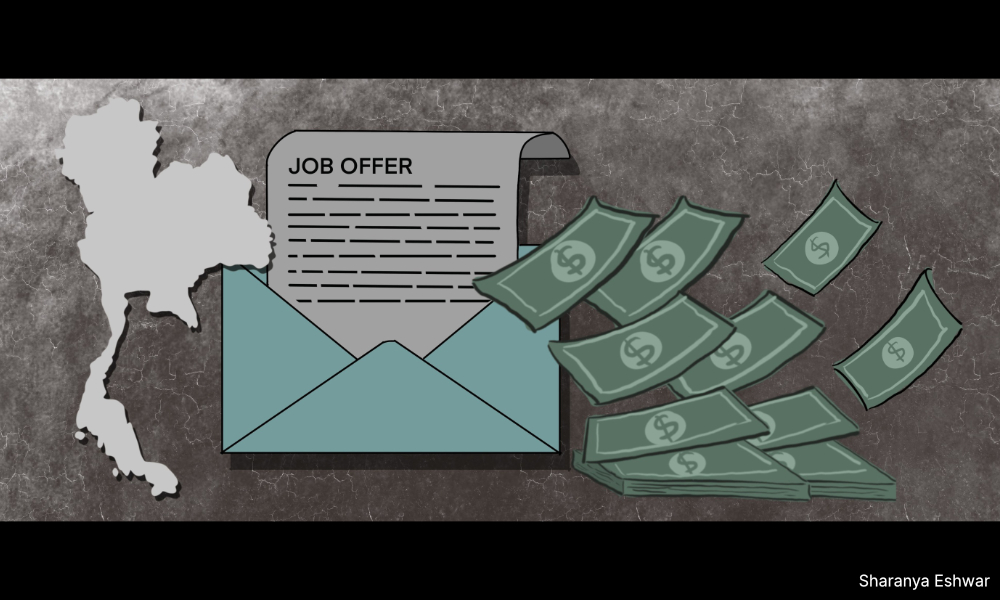

In early 2022, the 27-year-old engineering graduate was in his hometown Dhaka, the capital city of Bangladesh, when a school friend whose father ran a local recruiting agency offered him a job he couldn’t refuse.

It was for data entry that would fetch him a monthly income of nearly US$800 (RM3,698.80), an amount that dwarfed his paltry earnings at a garment factory.

Bangladesh’s garment industry, which caters to international fast-fashion brands, is known for its abysmal minimum wage.

In the factory, Salam’s monthly income was just US$300 (RM1,387.05). But this job offer, although promising, had one caveat - moving to Cambodia immediately.

Cambodia, the school friend told Salam, is a new destination for migrants.

“He said I have the best education in engineering. I’m able to speak English,” Salam told Asian Dispatch.

“I was the perfect person for this job, I was told.”

Salam had never travelled outside his country but as the sole breadwinner of the family, he said yes.

With no Cambodian diplomatic mission in Bangladesh, the recruiters took a fee of US$3,000 (RM13,875.50) – which Salam paid by mortgaging his family farmland and taking a loan – to book a one-way flight ticket and a tourist visa.

He was told he will be able to recover that money once he starts working and his visa will be converted for his employment. But once he was there, he had a shocking revelation.

‘Sold off’

His “workplace”, which was a casino called Long Beach, was located in Cambodia’s special economic zone called Dara Sakor, 250km from the country’s capital Phnom Penh.

There, his passport was taken and he was handed a computer, 10 iPhones, and 5 SIM cards.

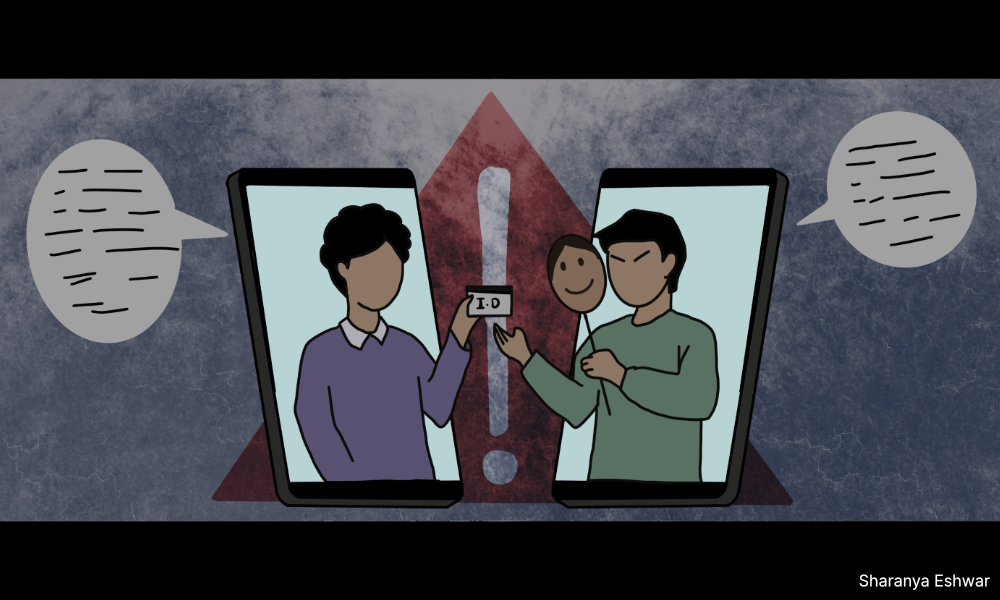

His job, he was told, was to impersonate a young Chinese model through dozens of social media accounts to ensnare male victims and scam them into investing in fraudulent crypto schemes.

When he tried to call the Bangladeshi broker who “recruited” him, he was ghosted. He knew then: “I had been sold off.”

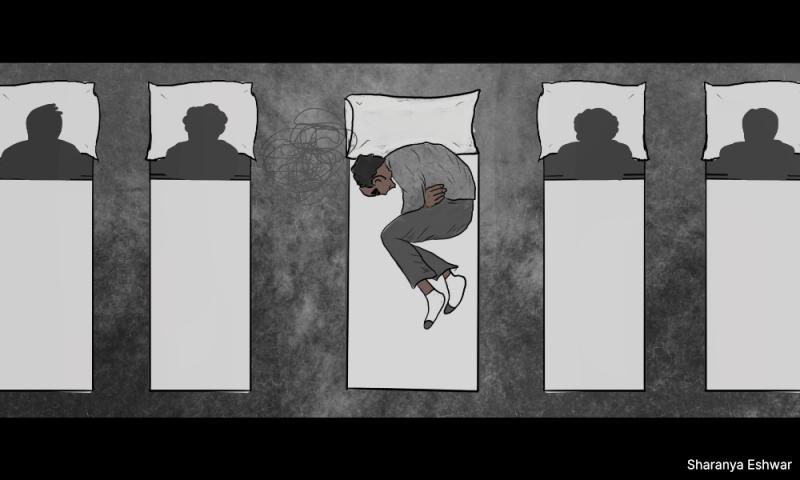

For the next five months, Salam went through what he described to Asian Dispatch as torture – both mental and physical – in the scam centre that housed men from across South Asia.

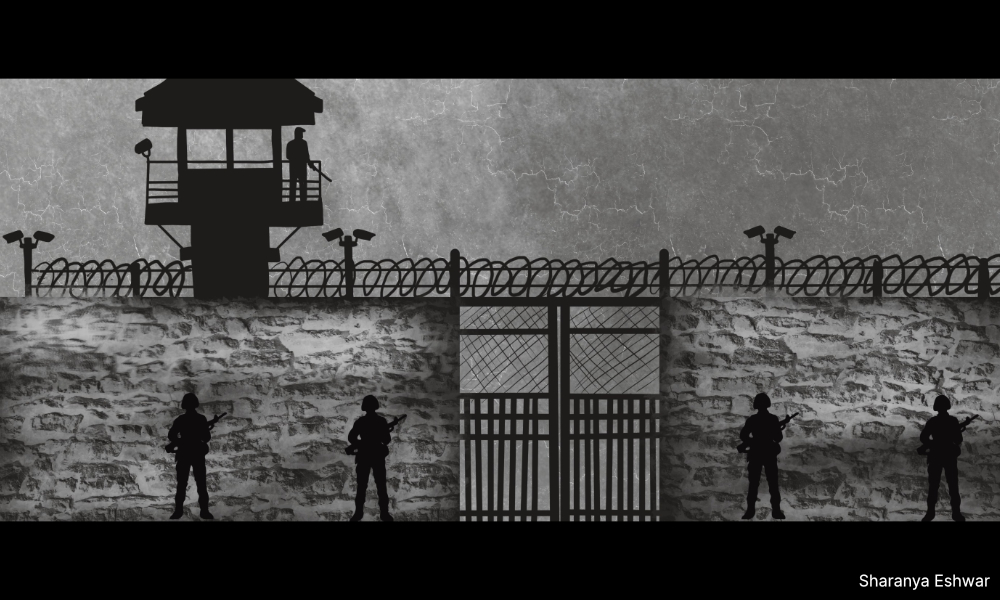

His employers, who he later found were Chinese nationals, beat him with baseball bats and gave him electric shocks if he failed or refused to work. Outside, the compound was surrounded by gun-toting security guards.

“Unless you’ve seen (the crime) for yourself, you’ll never know how horrible it is,” said Salam.

“I was forced to work as (the scam centre’s) slave and at one point, I didn't care about the people getting scammed because of the torture I faced. I didn't want to end up dead.”

Salam was rescued by an anti-trafficking NGO in September 2022. His story is among hundreds of thousands, according to a United Nations estimate, who have been similarly trafficked by criminal gangs and tortured into running illegal crypto scams in Asia.

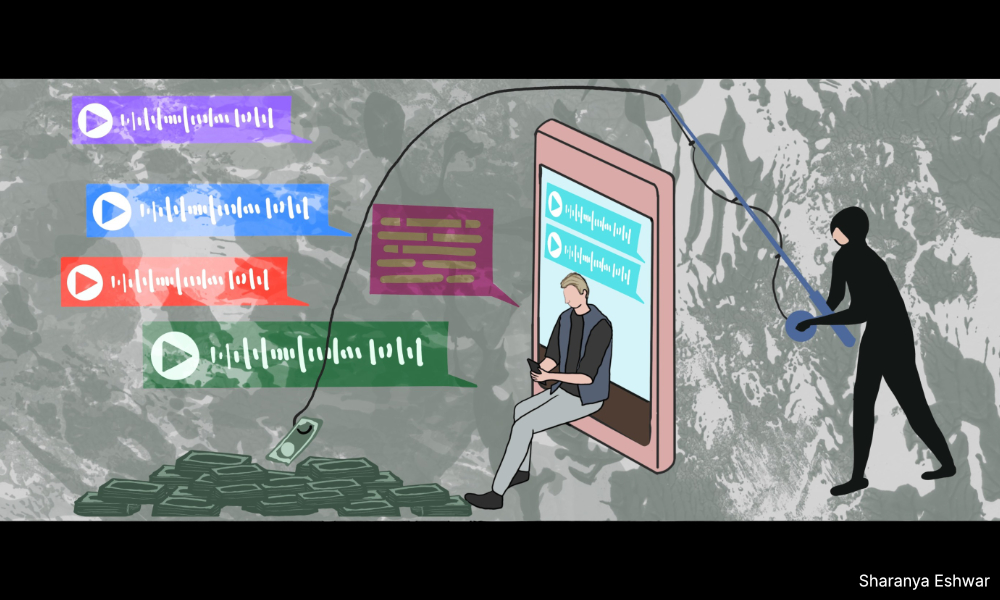

Pig-butchering scams, as the crime is now widely called, derived its name from the farm practice of fattening pigs before slaughter.

The crime involves scamming people after building online relationships with the end goal of exacting money.

As of February this year, as much as US$75 billion (RM346.76 billion) is estimated to have been moved to crypto exchanges through scam compounds in Cambodia, Thailand, Myanmar and China.

But what is of particular note is the trafficking of South Asians to operate these scams.

Once among global leaders in IT skills and services, South Asian techies are increasingly being lured into pig-butchering crime hubs as they struggle with post-pandemic economic slowdown and global tech layoffs.

Salam said he was sold thrice by compound owners in slave-like conditions. He returned to Dhaka empty-handed while his captors had exchanged tens of thousands of dollars to sell him.

Anti-trafficking organisations have found that scam compounds across Southeast Asia are heavily barricaded and deployed with armed men, making it impossible for trafficked victims to escape.

There is no official estimate of the trapped South Asians but in Bangladesh, a 2023 investigation by news outlet The Daily Star estimated thousands were trafficked and tortured in these scam centres.

In India, officials said they have rescued at least 250 citizens this year while news outlet The Indian Express reported the entrapment of around 5,000 Indians.

In countries like Nepal, Sri Lanka and Pakistan, the exact number of survivors isn’t known as governments continue to grapple with the crisis.

Economic crises at home a factor

Anti-trafficking NGO Global Alms CEO Mechelle Moore told Asian Dispatch said in a modern society, people are travelling all over the world for work.

“People aren’t getting jobs in their home countries and (the scam companies) take advantage of that desire to work overseas.”

Moore estimates at least 10,000 trafficking victims are stuck in scam compounds that could run up to hundreds if not thousands across Southeast Asia.

“A lot of (these scam) companies lure people who can speak English well, and the jobs advertised are for logistics, customer service, marketing and so on,” said Moore.

“They would specifically target people from South Asian countries that did not have an embassy where they’re operating out of.”

READ MORE: Can you escape online scams?

The pandemic provided a big advantage, if not the catalyst, to the criminal network. Civil strife and socio-economic struggles in the host countries add more layers to this complex web of transnational crime.

NGOs like Moore’s have been tracking the construction of new compounds across Asia every year.

“They’ve got enough people willing to complete the scams. If the survivors of trafficking don’t want to stay or cause trouble, they’re recycled,” she said.

“It’s definitely not dying down.”

Suresh Jayawardena, another pig-butchering trafficking survivor from Sri Lanka, was a “cyber slave” for eight months in Myanmar, where scam compounds have an additional perimeter of armed protection reportedly under the authority of the Myanmar military or its proxies.

Jayawardena, who is addressed with a pseudonym, requested anonymity to be quoted in the story due to the social stigma associated with the crime in his country.

Asian Dispatch spoke to him weeks after he was rescued among dozens of others in April after an intervention and a rescue mission was carried out by the Sri Lankan government.

Like Salam, Jayawardena, too, faced torture when he resisted participating in the crime, which included being stripped, blindfolded and electrocuted.

But what’s of note to many anti-trafficking experts is the platform the trafficking victims are given to defraud people.

In Jayawardena’s case, it was Telegram, where he offered fake investment opportunities to people desperate for healthy returns.

Social media not doing enough

“It’s clear to me that at various stages of the pig-butchering scam, the onboarding of victims of scams happens on (social media) platforms.

“This is an obvious win (for the scammers)," Erin West, a prosecutor from Santa Clara County in California, US, told Asian Dispatch.

West investigates crypto crimes with primarily American victims, and trains law-enforcement agencies across the US to trace cryptocurrency transitions.

A few months ago, she started “Operation Shamrock”, which brings together private and public stakeholders across the world, including big tech companies, to lead a concerted fight against pig-butchering scams.

During one of the meetings she held with big tech platforms, she told the representatives that their platforms were enabling the crime.

“They didn't appreciate the language and didn't want to cooperate,” she said.

“There’s a pressing need for global communities to be involved,” West adds.

“I don’t believe these people, the scammers, are untouchables.”

Troy Gochenour, who works at the Global Anti-Scam Organization (Gaso), said pig-butchering crimes are of “pandemic proportions.”

“We’re living in the age of scam-demic,” he told Asian Dispatch.

Gaso was set up in 2021 by victims of pig-butchering scams, which included Gochenour.

By 2022, the organisation had connected with 1,483 victims worldwide who had suffered losses to the tune of US$256 million (RM1.18 billion).

This means that every victim lost an average US$173,000 (RM799,865.50).

Gochenour, an American, lost US$28,500 (RM131,769.75) in a liquidity mining scam after developing an online relationship with an online profile of who he thought was an Asian woman called Kris Gia.

“The allure (of Kris) was her offer to provide me companionship. We would talk like we’re boyfriend-girlfriend or husband-wife,” said Gochenour.

“This is why this crime is so insidious because at the other end of the phone is someone who is trained to do this. The so-called relationship is a planned operation.”

Global scam operations

The victims of the pig-butchering scams aren’t always those in the West. Moore confirmed that the scam companies target those in Asian countries too, and hire people from that region to scam them.

“We’ve had Vietnamese trafficking victims who were trafficked specifically to scam people in Vietnam. Same with Indonesia, Malaysia, and China,” she said.

“It’s a global effort.”

The story of Sandun De Silva from Sri Lanka illustrates this. The 34-year-old journalist, who also spoke to Asian Dispatch on condition that he can use a pseudonym, was introduced to a Telegram group last year after he accepted an online content writing “job” that was attached with a fraudulent investment opportunity.

All the administrators in the group texted in and spoke Sinhalese. De Silva lost his family savings amounting to US$4,000 (RM18,494). Even to this day, the father of two hasn’t told his family about it.

PLAY THE GAME: Can you escape online scams?

Gochenour said that the first thing tech platforms should do is take down fake profiles when they’re reported.

This feature, especially on Meta, is often automated, which Gochenour said doesn’t always resolve the problem.

In India, Meta, in its April report, documented receiving over 27,000 reports of fake profiles on Facebook and Instagram but admitted a significant chunk of them were not actioned.

“Unfortunately, there’s not a lot that has been done by these platforms themselves,” Gochenour added.

“Law enforcement has, at times, shut down platforms, but that is only if they're connected to a particular case they’re working on.”

In May, leading tech firms - Match Group, Coinbase, Meta, and Ripple - formed a coalition called Tech against Scam to respond to and prevent online fraud and financial schemes that target consumers through their platforms.

Asian Dispatch reached out to Telegram and Meta to understand how they’re tackling these crimes but didn’t get any responses.

Struggle continues after rescue

Early this year, when Asian Dispatch reached out to Salam in Dhaka, he had been back home for a few months.

Unlike all survivors quoted in this story, he chose not to be anonymous. Gaso rescued him in 2022 after he covertly reached out to them while living at the scam compound.

Gaso had pressured his “bosses” to release him along with a few others.

However, Salam’s struggles didn’t end there. During his captivity, he exceeded his visa duration by over 100 days. Since his compound employers did not pay him, he didn’t have money to pay the visa fine and buy a flight ticket. He was finally sponsored by a friend.

Once home, a battered Salam underwent spinal surgery for injuries inflicted by the torture. He also struggled psychologically to come to terms with the time and money he lost in that period. But his family’s support helped him take his next steps.

“They told me, ‘It's fine you lost your money. At least you are still alive.’”

Today, he works for a non-profit called Humanity Research Consultancy (HRC), which facilitates survivors’ repatriation after they're rescued from scam centres.

“This is the right time for me to commit myself to this mission,” he said.

“To the mission of survivors’ rights.”

This article was first published in Asian Dispatch. Read the original article here.

RM12.50 / month

- Unlimited access to award-winning journalism

- Comment and share your opinions on all our articles

- Gift interesting stories to your friends

- Tax deductable