Floods, rising seas make dumps more dangerous

-

Editor’s note: This article was first published on Macaranga.org and is republished with permission.

The landfill looms like a Titan, 27 metres into the sky, a stark symbol of Malaysians’ mounting waste problem. That is as tall as a 4-storey building. Its decaying mound emits a foul stench, all from the waste we generate.

This is the Jeram landfill in Selangor, which receives waste from six local councils in the Klang Valley. Within 10 minutes, 30 trucks unload their contents onto the ever-growing heap. Every day, 1,000 rubbish trucks dump, on average, 3.7 million kilogrammes of waste into the landfill.

But far away from where anyone lives, it allows us to adopt the mantra of "out of sight, out of mind".

As Malaysia’s population not only grows but aspires for better living standards, we also generate more waste. With each passing day, our land disappears under ever-expanding mountains of trash, while toxic leachate seeps into the earth and poisonous landfill gasses taint the air.

And these are likely to worsen as climate change increases the frequency and intensity of floods, sea-level rise and droughts.

Good waste management is therefore urgent. How can we mitigate these harmful effects?

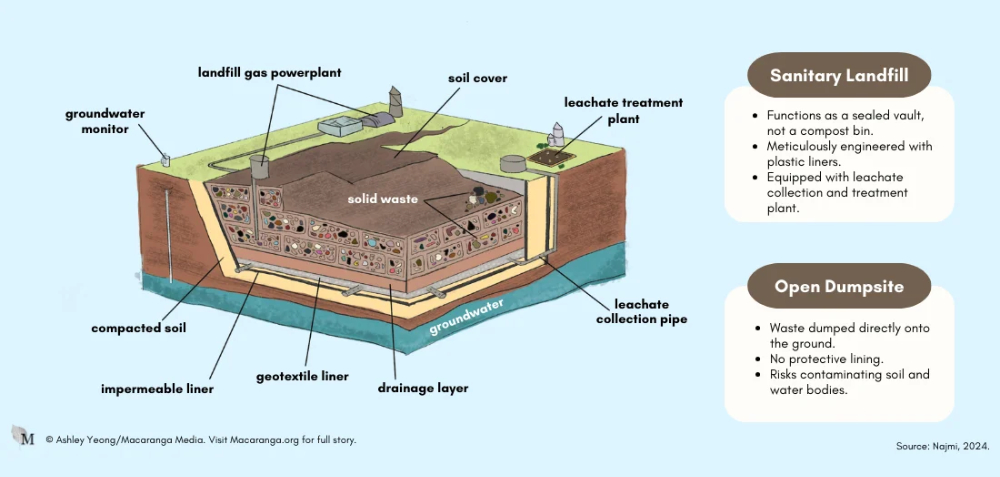

Managed by Worldwide Holdings, the Jeram landfill is a sanitary landfill. A sanitary landfill does not function like a compost bin but like a sealed vault for waste.

Once a landfill is filled up, the rubbish inside is meant to be locked away forever.

In fact, sanitary landfills are meticulously engineered and managed facilities, featuring a plastic liner to separate waste from soil and equipped with leachate collection and treatment systems.

In stark contrast, open dumpsites have no such safeguards. Waste is deposited on the ground, left to fester and decay. This leaves an unchecked flow of waste and leachate to freely contaminate the surrounding soil and water bodies.

Malaysia’s landfills were once all open dumpsites. Some were later converted to sanitary landfills. This conversion involves digging out rubbish and installing proper lining and treatment facilities.

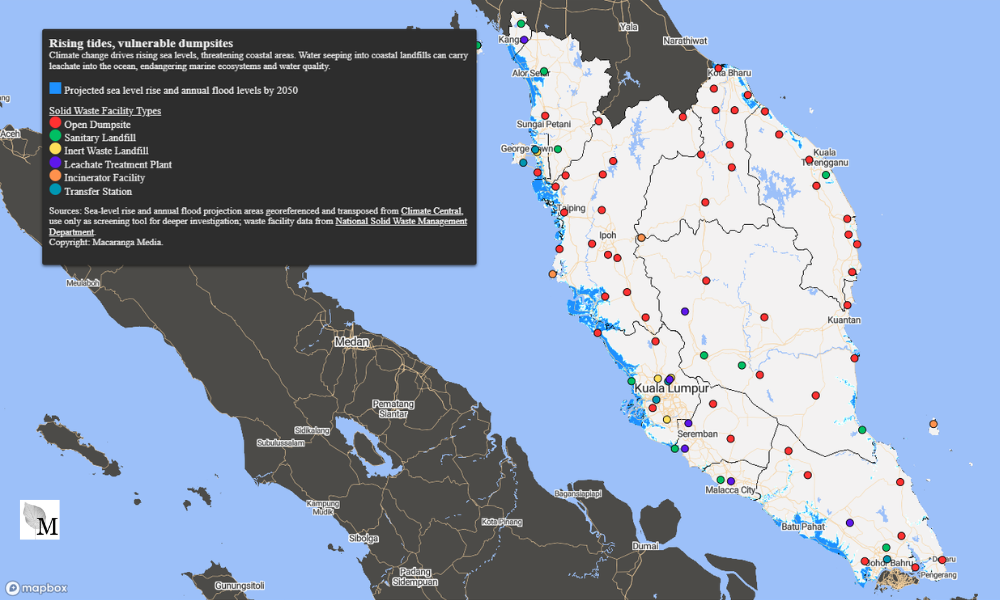

However, only 15 of Malaysia’s registered operational landfills are sanitary landfills. The remaining 116 landfills are dumpsites (Housing and Local Government Ministry, October 2023).

In addition, there is an unknown but probably large number of unauthorised dumps for household trash and hazardous waste. In February, the the ministry revealed that they closed 2,093 illegal waste dumping sites last year alone at a cost of RM1.6 million.

Without protective measures, dumps pose significant environmental and human health risks, heightened now by the climate crisis.

Note on sources: Ministry of Housing and Local Government (KPKT)’s map plots 15 landfills as sanitary landfills (as of Oct 2023) whereas its Time Series Statistics 2018-2022 lists 21 sanitary landfills.

'Garbage juice'

Leachate, often likened to “garbage juice”, forms when water seeps through waste, coming from rainfall or the waste itself.

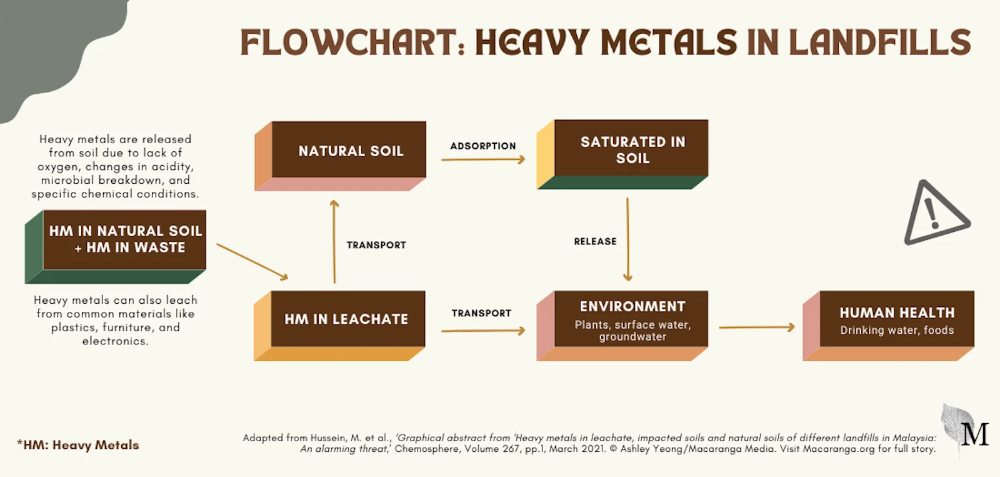

A major concern with leachate is the concentration of heavy metals it carries. These toxic substances leach not only from electronic waste but also from common materials like plastics, wood, and everyday household items like milk cartons. They also already exist in natural soil.

Without bottom liners, leachate collection, or treatment systems, untreated leachate seeps into the soil and pollutes nearby waterways through runoff.

“Heavy metals are inorganic and non-degradable. They stay in the environment, remaining in the soil for many years,” said Munirah Hussein, who has researched heavy metals in leachate.

Unlike organic matter, heavy metals can persist within landfills for over a century.

She said of the heavy metals, arsenic, one of the most toxic heavy metals, is most common. Arsenic is particularly alarming because it cannot be detected due to its odourless and tasteless nature.

As arsenic migrates from landfills into waterways, it can disrupt aquatic ecosystems and potentially cause cancer and other health problems in humans exposed to contaminated water.

“The solubility and mobility of arsenic are further exacerbated by increasing alkalinity (pH levels) and salinity (salt content) in groundwater and sediments, heightening the risk of environmental contamination.”

Climate change is also worrying, noted Munirah, as it brings increased floods and wetter days. Quite simply, the wetter the landfill, the more pollutants leach out of the waste.

“The critical thing is for sanitary landfills to have (a layer of soil on top) to reduce direct contact of waste with rainwater,” she said.

Floods mean more rubbish

Hydrology expert and flood researcher Edlic Sathiamurthy agrees, noting that a warming Malaysia can also intensify heavy metal leachate risks.

“Higher-than-average temperatures can make chemical processes more active. Leachate is a cocktail of all kinds of materials,” he said.

“We have not even factored in air pollutants causing acidic rainfall, (which) would further react with the rubbish.”

Another climate change impact of concern is rising sea levels. These pose a problem for coastal landfills, allowing water to seep in and carry leachate into the ocean. This would harm marine ecosystems and lower water quality.

This is the case for the 16ha Pulau Burung landfill in Penang, said Edlic, who grew up near that landfill.

He gestures at a map of the landfill and humorously points out a gazebo along a running track. “You could sit here and smell the fresh air of rubbish,” he said cheekily.

But turning serious, he said that Pulau Burung’s coastal location has become a real problem.

Overflowing leachate

“During heavy rain, the leachate pond can overflow. But with climate change, it’s not just about rain – it’s also about sea level rise, wave height and storm surges,” he explained.

During spring tides and storm events, waves can reach further into the land, flowing into the leachate pond.

The threat from rising sea levels is not limited to Pulau Burung, he warned.

“If it’s an old landfill in a coastal area, then it is subjected to the same problem. Can you imagine an event like that? Water overtops, mixed with the leachate and goes back into the sea!”

Fire risks grow

As temperatures rise with climate change, so does the risk of landfill fires. On a hot and dry day, only the landfill’s bottom may be in contact with water, explained Edlic.

“The top is dry. As materials decompose, methane gas builds up, potentially causing explosions”.

Pulau Burung alone has caught fire multiple times, fires which are tough to extinguish if they are sub-surface. In 2022, fires there took up to three weeks to extinguish.

With warmer days, the risk of landfill fires increases, warned Environmental Protection Society Malaysia’s vice-president Randolph Jeremiah.

“Prolonged drought is a major contributor (to) heat buildup within a landfill. The presence of methane increases the intensity of a fire.”

He cited past fires in the Bukit Bakri Muar landfill and Pekan Nenas Pontan landfill during the 2018 drought.

What’s more, when landfills catch fire, they release dangerous pollutants into the air, causing health problems like respiratory issues.

In March, a landfill fire in Kota Kinabalu, Sabah forced nearby schools to close early and students to wear face masks because of poor air quality and hotter temperatures.

The siting of new waste facilities should consider climate risks like droughts, floods and sea level rise to minimise operational and environmental risks, added Jeremiah.

Filling up fast

The problem is not just in properly lining and treating waste in landfills. Worldwide Holdings, which manages the 117ha sanitary landfill in Jeram, reports that landfills are nearing capacity much earlier than expected because trash is growing so fast.

For example, in 2021, it had to take in an additional five million kg of waste from Shah Alam’s Taman Sri Muda flood alone.

Once full, new land would need to be opened for new landfills, or alternative waste management methods explored. Worldwide’s solution is incineration, or Waste-to-Energy (WtE) plants.

“With WtE, [our landfill] can go for another 20 years,” said Najmi Mohamad Saifullah, senior engineer at Worldwide.

Worldwide’s WtE facility, which is being constructed, is Malaysia’s largest. The 12ha facility will be in Jeram and is expected to start operating in 2026.

It will be able to generate up to 52 MW of energy for the national grid, roughly 410,000 households.

Burning waste viable?

As the land available diminishes, incineration emerges as an alternative. In Malaysia, plans for 7 WtE facilities are underway.

However, Greenpeace Malaysia’s Thing Siew Shuen cautions against this approach, calling instead for a shift towards sustainable lifestyles.

Without addressing excessive plastic and food waste at the production stage, any solution remains incomplete, Thing argued.

“Whether it’s landfills or incinerators, the continuous investment in these facilities represents a misallocation of public funds and mismanagement of resources.

“Sending waste to landfills is akin to draining water from a flooded bathroom without first turning off the tap.

"Excessive plastic and food waste could be significantly reduced at the production stage, for instance, by replacing single-use plastics with reusable and refillable options.”

But Najmi points out WtE’s added plus: reducing greenhouse gas emissions. Landfills emit methane, a greenhouse gas that is 28 times more potent than carbon dioxide.

He said the simplest way to reduce the amount of methane being released into the atmosphere is to burn it and turn it into carbon dioxide.

But carbon dioxide is also a greenhouse gas: burning one kg of municipal waste emits carbon dioxide to the tune of 0.7 to 1.1 kg.

Nonetheless, Worldwide also collects landfill gases to generate electricity.

A future without landfills

Greenpeace’s Thing looks forward to a time without landfills as society embraces sustainable lifestyles.

“Can we envision a future where more landfills are closed, as more people reject single-use, throwaway and convenience-driven lifestyles in favour of reuse and refill practices?”

Worldwide’s Najmi actually agrees.

“I won’t call myself a recycling freak, but looking at all the waste, I definitely try to sort out my plastic,” he said with a wry smile. Being in the waste management industry for more than a decade has influenced his daily lifestyle choices.

Edlic echoes this sentiment.

“Plastic takes years and years to decay. Why do we have waste in the first place? It’s because of the inefficient use of resources, and our consumption behaviour.

“We have many things that we don’t actually use and don’t actually need. There has to be a paradigm shift in how we consume, along with stakeholders, industries and the commercial sector, to change.”

Macaranga and Malaysiakini are part of Asian Dispatch, a network of Asian newsrooms.

RM12.50 / month

- Unlimited access to award-winning journalism

- Comment and share your opinions on all our articles

- Gift interesting stories to your friends

- Tax deductable